Reform of the United Nations Security Council and the Role of Latin America

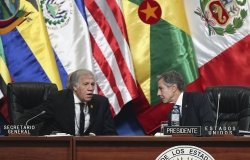

A distinguished panel discussed the evolving role of the UN in world affairs and how the nations of Latin America fit into the organization. Participants included Ambassador Heraldo Muñoz, former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who also served as United States ambassador to the UN, and Emilio Cárdenas, former Argentine ambassador to the UN. Video of this event is now available.

Overview

Video of this event is now available. To watch the video, follow the links in the "See Also" box to the right of this screen.

Panelists:

Madeleine Albright, Former Secretary of State and former US ambassador to the UN

Emilio Cárdenas, Former Ambassador to the UN from Argentina

Heraldo Muñoz, Ambassador to the UN from Chile

On April 18, 2005, the Woodrow Wilson Center convened a panel of former and current ambassadors to the United Nations to discuss the recently rekindled topic of UN reform and how Latin America fits in the process. Joseph Tulchin, Director of the Latin American Program, and David Birenbaum, a senior policy scholar at the center, gave the welcoming remarks and introduced the panelists. [Birenbaum is a former US ambassador to the UN under UN Management and Reform, and is currently conducting a study on UN reform.]

Madeleine Albright outlined a web of factors which defines the context of UN Security Council reform today. She touched on the United States' reputation as the member country that is quick to push for reform, yet quite slow in paying its dues. Reformers in 1993 as well as today have been presented with the primary task of making the Security Council more representative of today's global power structure. However, this proves an extremely difficult undertaking because the process gets flooded with candidates for permanent seats and veto power. In addition to this, said Albright, intricate alliances form during the negotiations, each conditioning their vote on different, often contradicting propositions. This happens on top of pre-existing alliances from strategic caucuses to major regional organizations such as the European Union.

Emilio Cárdenas started with the point that UN reform reaches far beyond the Security Council to other organs such as the General Assembly, and comprehensive reform may call for amending the UN Charter. Cárdenas recognizes UN reform as a process starting about 12 years ago with what he referred to as the "quick fix" of granting Germany and Japan permanent seats. He highlighted the paradox that these two countries, considered the enemy in the Charter, are now the second and third largest contributors to the UN. However, the "quick fix" was not approved because too many countries conditioned support on their own membership. Shifting the focus to Latin America, Cárdenas observed that some countries, including Mexico, have no desire for a permanent seat on the Council, and that Brazil is the only one that has expressly campaigned for a seat. On motives for Latin American countries to seek a permanent seat, he included greater access to the world's powerful countries, a "cascade effect" of permanent members winning board membership at UN agencies, and status as the representative of the region. Reflecting on his days as permanent representative to the UN, he said that Argentina did not seek permanent status because its government did not think that reform would ever materialize, and at the time it was right. Even today, Cárdenas believes it is unrealistic to expect reform to be completed by the end of this year, as the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, has called for. Finally, Cárdenas warned of the potentially dangerous economic and global security consequences in the recent diplomatic flare-up between China and Japan.

Heraldo Muñoz listed several factors which may contribute to a higher probability for Security Council reform today, including gobal power shifts, the oil-for-food scandal, and the war in Iraq. On this last point, he noted that despite going around the Security Council before the war, the US still came back for cooperation with the interim government, construction of infrastructure, and the Iraqi national elections. Also, while the near guarantee of East-West vetoes during the Cold War tended to leave the Security Council in a stagnant state which shifted decisions to the General Assembly, resolutions and other activities have significantly increased since the early 1990s, and today the Security Council enjoys a renewed relevance. Trends like these mean that everyone benefits from a vibrant, effective UN, the main piece of which is the Security Council. Muñoz similarly noted a problem of too many candidates. The reform proposal which calls for one representative for "the Americas", as opposed to 2 each for Asia and Africa, also poses a significant disadvantage for Latin America. Criteria for membership is far from clear, but may include GNP, GNP per capita, financial and other resource contributions, and general diplomatic initiatives. Muñoz agreed with the point that complete UN reform requires many changes beyond the Security Council, including measures to depoliticize the Human Rights Commission, clarify guidelines for the legitimate use of force, and broaden the role of post-conflict reconstruction. In closing, Muñoz called for a "New Deal" at the United Nations, consisting of inclusive reform that would benefit even those nations with no prospects of a permanent seat on the Security Council.

Birenbaum then opened up the discussion to questions. When asked about new criteria for the use of force, Albright responded that this would be helpful, while noting that the Security Council already has the ability to act preventively in various alternative ways, including by force. A major obstacle to consensus would be a clear definition of terrorism. In addition, Albright also believes that a peace-building commission with a strong enough mandate could potentially have many volunteers. Cárdenas stated that he did not think the United States was ready for Security Council reform, including any delineation of use of force criteria, and that to push the US would effectively kill the window of opportunity. The only answer to this dilemma would be to call for more time. Cárdenas added that the Human Rights Commission is a shame to us in its current state, but that efforts towards democratization should spread beyond the commission to all organs of the United Nations.

Written by Joseph Tulchin with help from Alana Parker

Hosted By

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Thank you for your interest in this event. Please send any feedback or questions to our Events staff.