A blog of the Latin America Program

Psychological meltdown: Number three

LAP

Argentina is once again on the verge of a crisis. Not an economic crisis this time, more like a psychological crisis: Following the recent peso devaluation, Argentina might be surpassed by Colombia as the 3rd-largest economy in Latin America.

For Argentines, national pride comes naturally. But for a century, the country’s economic performance has often challenged its self-esteem. Argentina has never emotionally recovered from its heyday in the late 19th century, when its economy was one of the richest in the world. The most severe setback, both economic and emotional, was the 2001 meltdown and its brutal aftermath. After that crisis, Argentina saw a decade of rapid growth that suggested a possible new period of prosperity. But mismanagement and corruption under the Kirchner governments spoiled the gains of this period. Earlier this year, President Mauricio Macri’s inability to correct for his inherited fiscal imbalance led to another economic crisis, including a collapse in the peso’s value.

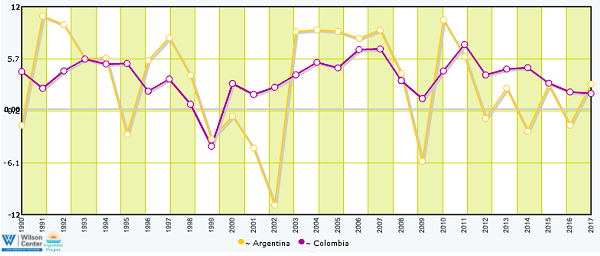

Now comes another potential indignity. Sometime soon, depending upon the peso’s performance, Colombia may replace Argentina as the third-biggest economy in the region, after Brazil and Mexico. Colombia is projected to grow by 2.7 percent this year and 3.1 percent next year, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit. By contrast, Argentina’s economy will contract this year by 2.2 percent and grow next year by only 0.3 percent. That continues a period of catch-up by Colombia, amid Argentina’s infamous booms and busts (see graph above, using data from the United Nations’s Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe).

Last year, Argentina was still comfortably ahead, with a GDP of $638 billion, compared to $314 billion for Colombia. But this year, the International Monetary Fund projects Argentina’s GDP will fall to $475 billion, while Colombia’s climbs to $336 billion. The International Monetary Fund’s latest estimate puts Argentina on top at least through 2023. But to meet those expectations, it will need to find a sustainable path towards fiscal balance, inflation management and a stable currency.

Aplauso, medalla y beso: Only at Olivos

LAP

After getting tangled up in U.S. protectionism, Mr. Macri has begun to cash in on his close relationship with President Trump. Throughout this year’s economic crisis, the White House and Treasury have steadfastly backed Argentina’s pleas for IMF support. Out: Paul O’Neill’s hand-wringing about moral hazard. In: The IMF’s largest-ever bailout, a $57 billion loan to stop a run on the peso.

In public remarks, the Trump administration has also been relentlessly supportive of its allies in Buenos Aires. Following the latest adjustment to the IMF loan agreement, Steven Mnuchin, the U.S. treasury secretary, said optimistically that the revised conditions would put Argentina “on a path of sustainable growth.” There remain disagreements – “irritants” in diplomatic parlance – including U.S. tariffs that shut Argentina out of the lucrative U.S. biodiesel market, and a U.S. ban on Argentine beef in place since 2001. But when Mr. Trump arrives in Buenos Aires for a G-20 summit late next month, he will be embraced unreservedly by his hosts.

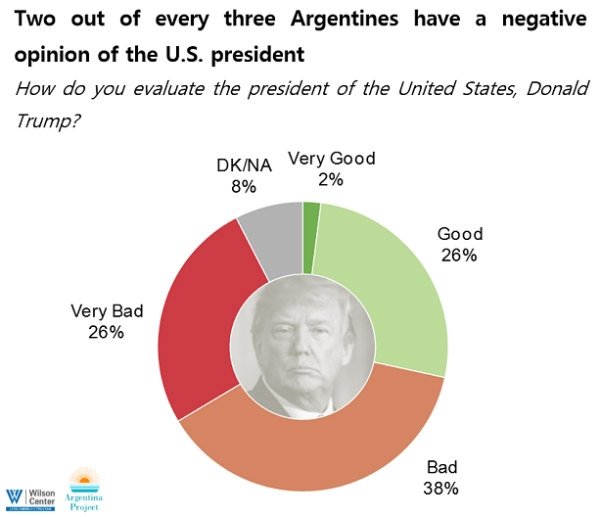

But what about the public reaction? Don’t expect spectators to shower the presidential motorcade with sweets and flowers. In the latest Pew report, released October 1, only 32 percent of Argentines expressed a favorable view of the United States, compared to 43 percent during the last year of the Obama administration. Seventy-four percent of Argentines do not believe the United States considers Argentina’s interests in developing U.S. foreign policy. Stunningly, more than one-in-three Argentines (35 percent) would prefer Chinese global leadership to a U.S.-led world – the worst performance for the United States in Pew’s 25-country survey.

That raises the question of whether Mr. Macri, who faces a brutal reelection campaign next year, will pay a political price for his close ties to Washington. Here, the answer is less clear. Thirty-three percent of Argentines say relations with the United States improved during Mr. Trump’s second year in office, according to the Pew survey. Moreover, support for the United States is far higher among the president’s political base. This month, we partnered with the leading Argentine polling firm, Poliarquía, to launch a nationwide survey measuring Argentine views of international issues. Though we also found generally negative views of Mr. Trump, support was significantly higher (35 percent) among Mr. Macri’s supporters than in the general population (28 percent).

‘Cambios profundos’: Argentina @ UNGA

Anahi Hurtado

What goes up: Is going higher

The severity of this year’s economic crisis has forced Mr. Macri to give up on some of his core principles. The first was gradualismo – the steady reduction of the large budget deficit left by the previous government (6 percent of GDP in 2015). Mr. Macri had tried to shield the poorest Argentines from budget cuts, and to promote growth even while cutting spending. But gradualismo depended upon affordable access to international credit, which dried up abruptly earlier this year. That thrust Mr. Macri into the arms of the IMF, and into a $57 billion Stand-By Agreement that requires a primary balance next year.

But gradualismo was not the only casualty of the IMF program. Mr. Macri’s initial reforms had involved reductions to the excessive tax burden left by previous governments – especially distortionary export taxes on agricultural products and minerals. Those taxes were first imposed as emergency measures following Argentina’s 2001 economic meltdown, and later expanded by the Kirchners. After taking office, Mr. Macri eliminated most export taxes, and pledged steady reductions for taxes on soy exports. In a reform last year, he also reduced payroll taxes and the corporate tax rate.

But the IMF bailout has forced Mr. Macri to stall, or even reverse, core elements of his tax program. For now, for example, there will be no further reductions on soy export taxes. What’s more, to meet the IMF’s fiscal targets, Argentina has increased taxes on all exports. The government justified the new taxes – which represent almost all of the projected revenue growth in next year’s budget – by pointing to the peso’s devaluation, which should make Argentine exports more competitive. Nevertheless, it represents a sharp reversal for the pro-business administration. Meanwhile, Mr. Macri is also eliminating some income tax deductions for the middle class, further angering unions.

Mr. Macri’s tax cutting dreams were not merely a standard wish list for a center-right party. Rather, the country he inherited had some of the region’s highest taxes, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. In 2015, tax revenue in Argentina equaled 32 percent of GDP, compared to an average of 23 percent in Latin America. That helped pay for a massive expansion in public spending under the Kirchners, but it also discouraged investment and sapped growth.

Though the tax hikes are a bitter pill for Mr. Macri, it could have been worse. Long before the IMF program, his gradualismo had begun reducing the primary deficit; the deficit this year is projected to be half the size of the 2015 shortfall. That said, much depends on the performance of the economy next year. Export taxes will likely be lucrative, as the government expects exports to jump by 21 percent, thanks in part to a recovery in the drought-plagued farm sector and economic growth in Brazil, Argentina’s top trading partner. However, the IMF expects the overall economy to shrink by 1.6 percent, which would eat into other sources of tax collection. The government is more optimistic about a recovery from this year’s recession. But if it’s wrong, it could face additional pressure to raise taxes yet again.

Related Programs

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more