The Broken Engine – How Europe Can Get Moving Again

Presidence de la Republique

The European Union’s proudest achievement, in the view of its founding fathers, was to make war between France and Germany unthinkable. For five centuries, every generation on both sides of the Rhine river were either engaged in bloody combat or preparing for conflict. The permanent cessation of this nonstop cycle of bloodshed was seen as a necessary first step toward peaceful reconciliation of the continent.

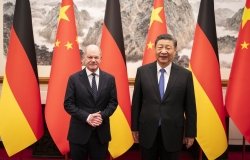

In the postwar era, successive French and German leaders made a priority of setting aside conflicting perspectives and building close personal partnerships. Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer launched the concept of a French-German tandem that guided Europe from wartime devastation to unimagined prosperity. Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and Helmut Schmidt bonded as finance ministers and later as national leaders charted a path toward Europe’s single currency. François Mitterrand and Helmut Kohl, despite their disparate temperaments and ideologies, steered Europe through the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of a reunified Germany.

Yet today, the vaunted motor of European unity is stalled and in dire need of repair. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, uncertainty over America’s security commitment to Europe, and how to govern a future European Union that could soon grow to 35 members have called into question the model of French-German leadership that has shaped the destiny of Europe for the past eight decades.

The historic split has been magnified by a personality clash between French president Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz. Macron relishes his role as a disruptive provocateur, willing to shake up other leaders and compel them to take bold and decisive action beyond the least objectionable option. His powers as president of France ensure a near total monopoly over his country’s foreign and security policy. Scholz, on the other hand, is a cautious and stubborn Social Democrat lawyer who hates to be pushed into accepting rash judgements. He must also juggle the demands of a contentious three-party ruling coalition, including pro-Russian and pacifist factions within his own party.

Their biggest argument has been over how Europe should respond to the threat of a belligerent Russia and support Ukraine in its desperate efforts to thwart the territorial ambitions of Vladimir Putin. Macron, who once insisted the West must not humiliate Russia and sought to include Moscow in a new European security order, now says he was betrayed by Putin’s lies and insists Europe must do everything in its power to prevent a Russian victory over Ukraine. He warned that Europe will be “sleepwalking into catastrophe” if it allows Russia to win the war and that Western allies should not rule out sending troops to Ukraine.

“Europe clearly faces a moment when it will be necessary not to be cowards,” Macron said during a visit to Prague in early March. That comment infuriated Scholz and other German officials who believe the Nazi past requires their country to make painstaking efforts to avoid being drawn into conflicts beyond its borders. Germany’s defense minister Boris Pistorius retorted “we don’t need, from my perspective at least, discussions about boots on the ground or having more courage or less courage.”

But Macron persisted in claiming that Western allies needed to take firm stand to dissuade Moscow from further aggression that would jeopardize European security. He said Europe and the United States must maintain “strategic ambiguity” about what steps they were prepared to take in their support of Ukraine. “If, faced with someone who has no limits, faced with someone who crossed every limit that he had given us, we tell him naively that we won’t go any further than this or that – at that moment, we are not deciding peace, we are already deciding defeat. And if Russia wins this war, Europe’s credibility will be reduced to zero,” Macron said in a French television interview.

Like the Biden administration, Scholz’s government has rejected sending any troops or advanced weaponry that could bring the West into direct confrontation with Russia. Despite pleas from Ukraine and Germany’s opposition Christian Democrats, Scholz has refused to send long-range Taurus missiles to Kyiv because they are capable of hitting targets deep inside Russia. Nonetheless, Germany remains by far Europe’s leading contributor of financial and military aid to Ukraine, which has assumed greater importance with a $60 billion American aid package blocked in Congress. Noting France’s relatively paltry amount of aid delivered so far to Ukraine, Germany’s deputy chancellor Robert Habeck said instead of considering the dispatch of troops, France “should give Ukraine the munitions and tanks that can be supplied now.”

Like other European nations that still rely on NATO and the American nuclear umbrella, Germany has been reluctant to follow Macron’s lead in pushing too hard for greater “strategic sovereignty” in Europe. The phrase has become diplomatic code for curtailing Europe’s dependence on the United States as American foreign and security policy has shifted toward China. Many Europeans now concede that Macron has a point in his repeated exhortations that Europe must do much more to protect its own interests at a time when a resurgence of big-power rivalry pitting the United States against Russia and China risks drawing Europe into conflicts against its will. That conviction has become even more urgent with the prospect of Donald Trump winning the White House and making good on past declarations about pulling the United States out of NATO.

But foreign and security policy is not the only obstacle to getting the French-German engine purring again. The “big bang” expansion of the European Union that embraced former communist states of the Soviet empire has shifted the EU’s center of gravity toward the East. The prospect of further expansion, including several Balkan states and eventually even Ukraine and Turkey, means that the European Union will need to dramatically overhaul its decision-making machinery and even its basic institutions. What was possible to achieve as a twelve-state union will become inconceivable if the EU grows to as many as 35 members in coming years.

Even though France and Germany still represent the EU’s biggest economies and populations, they no longer seem capable on their own to dictate the course of the EU’s development. The estrangement between Europe’s two major powers has been percolating for several years, with policy conflicts on everything from nuclear energy to the size of EU budgets blocking progress toward the construction of a more responsive Europe that can meet the demands of nearly 500 million citizens.

In the future, France and Germany will need to include other key nations in the power hierarchy of Europe. On some matters, such as dealing with the challenge of illegal immigration across the Mediterranean, Italy and Spain will become increasingly vital partners in finding effective solutions. A promising new event appears to be the resurrection of the “Weimar Triangle” that would include Poland as part of an EU triumvirate. In the 1990s, this trio of nations helped prepare the path toward NATO and EU membership for Baltic, Central and Eastern European states.

Now that a pro-Europe government headed by former European Council president Donald Tusk has returned to power in Warsaw following eight years of rule by the rightwing Law and Justice party, there are hopes that Poland can become the next major player in EU decision-making. Tusk has already made it clear that he believes Poland can help alleviate tensions between France and Germany and get Europe moving again. He has a proven record in conflict mediation, having brokered a last-minute deal in 2015 that kept Greece in the Eurozone and defused a major financial crisis that could have shattered the single European currency.

At a three-way summit in Berlin held on March 15, the leaders of France, Germany and Poland emerged with big smiles and fresh promises to find ways to reconcile their differences concerning Ukraine, Russia and the future of Europe. At a meeting earlier that week with President Biden at the White House, Tusk vowed the three EU powers were determined to work together and make a big impact in shaping Europe’s future. “More and more attention will be paid to the triangle of Paris, Berlin and Warsaw,” Tusk said. “In my opinion, these three capitals have the task and the power to mobilize all of Europe.”

About the Author

William Drozdiak

Author "The Last President of Europe: Emmanuel Macron’s Race to Revive France and Save the World"

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe” – an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more