312. Trafficking Women after Socialism: from, to and through Eastern Europe

Gail Kligman is Professor of Sociology and Director Designate of the Center for European and Eurasian Studies, University of California-Los Angeles. She presented a paper that she co-wrote with Stephanie Limoncelli at an EES noon discussion on March 11,2005. The following is a summary of her presentation. Meeting Report 312.

The traffic in women and girls for prostitution has recently commanded the attention of state authorities, activists and academics the world over, although it is hardly a new phenomenon. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, increasing globalization, accompanied by population increases, urbanization, international migration, colonization and political upheaval contributed importantly to the growth of prostitution and the traffic in women and girls around the world. European countries, China and Japan supplied prostitutes to other countries. For example, French, Polish, Russian and Italian women went to brothels in other European countries, Argentina and Brazil while Chinese and Japanese women, including women of Korean ethnicity, went to brothels in colonial holdings such as British Hong Kong, the Dutch East Indies, French Indo-China, Manchuria, Singapore and Shanghai.

Though the extent of trafficking in women and its geographic routes have changed in the last hundred years, its structural causes and organization remain remarkably stable. Then, as now, traffickers used marriage or promises of marriage to recruit women and girls; others assured them of domestic service or entertainment work abroad. Still others enticed women already engaged in prostitution who then willingly left for foreign brothels. Whatever the particularities of the recruitment method, there has been no shortage of persons ready to benefit from the availability of women and girls: from procurers who have sold them, to pimps who take portions of their earnings, to brothel madams who have kept them in debt bondage, to local policemen who have had financial and other interests in keeping the brothel system alive and well. The boundaries between trafficking, prostitution and forced labor migration are often blurred, but trafficking involves deception and coercion, whether at the point of departure when women are recruited or when they arrive at their destinations.

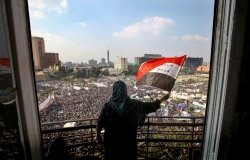

The contemporary traffic involves women from across the globe. The collapse of communism that began in 1989 provided new resources—geographical and human—for the sex trade, increasingly incorporating women from Eastern Europe. One of the most striking images of the changes soon after the fall of the Berlin Wall was that of women lining the highways offering sex for sale. Political and economic liberalization as well as internal and international militarism created new opportunity structures and daunting economic uncertainties that produced both a demand for and a supply of sex workers in and from Eastern Europe. Most of these sex workers have been and are women and girls. Whether working part-time to supplement income, or full-time voluntarily in sex clubs, or forced through trafficking, prostitution is a stable, ever-expanding feature of the global service economy. But in contrast to the neon lights advertising live sex shows or lap dancing clubs, trafficked women are largely invisible, hidden from the publicly commodified sex trades.

As European borders have become more porous and labor more flexible, the commodification and exploitation of sex as a form of labor have increased in scope and global reach. The collapse of communism catapulted the former socialist countries into the global economy. The availability of cheap labor and potential markets brought multinational corporations, banks and manufacturers to the region. Directors of pornographic films and magazines as well as international sex tourism agencies also flocked to the former socialist states where there was then little threat of institutional regulation and enforcement. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, shorter distances made it easier and cheaper to move women from eastern to western Europe rather than from Africa, South America or Asia. Across Eastern Europe, global secondary economic activities blossomed, including underground trafficking in persons, drugs, arms and organs.

Economic decline and increasing poverty are significant contributors to trafficking. A key feature of postsocialist change has been the restructuring of the labor market and of social inequalities. This restratification draws attention to class as a significant variable in trafficking: poverty, urban and especially rural, is a consistent factor, historically and comparatively. There appears to be a correlation between national poverty rates and sending countries. Many women engage in the diversity of "legal" sex trade opportunities because of the potential for higher incomes unobtainable in other occupations. Still others, enticed by apparent job opportunities elsewhere or offers to become the brides of men in other countries, find themselves sold into sexual servitude. However women come to "sell their bodies," it usually forms part of an economic strategy often endorsed by family members. Yet, they and the women in question are frequently uninformed about the risks such occupational opportunities abroad may entail.

Most recent reports on trafficking to, through and from Eastern Europe concur on the patterns of source, transit and destination countries, although the numbers presented vary considerably. The fast-tracked North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and EU accession countries, especially Poland and Hungary, are variously considered to be source, transit and destination countries. In Poland, women and girls are trafficked from further east—Russia, Ukraine, Belarus—to and through Poland. Polish women are themselves trafficked primarily to Western Europe. Hungary is generally considered more a transit than either a source or destination country, with women from further east brought to and through Hungary en route to destinations further west. However, since 1989, Budapest has become a sex trade capital, suggesting that Hungary is not viewed as a source country in large measure because so many Hungarian women work in the sex trade in Hungary itself. In 1998, Budapest had an estimated 300 sex clubs operating.

Scholars have long viewed the Balkans as the crossroads between East and West, and in the world of trafficking, they continue as such. Albania is a key source and transit country. Those being transited, mostly from Moldova and Romania, Ukraine and Bulgaria, continue on to Western Europe. UNICEF notes that "the main trafficking routes into Albania follow the arms and drug smuggling routes, through Romania, Serbia and either Montenegro or Macedonia." Romania is yet another source and transit country. Women from Moldova, Ukraine and other former Soviet countries are trafficked to Turkey, Italy, Greece and the former Yugoslavia. Romanian women have been trafficked to France, although some go voluntarily as sex workers. Bulgaria is another source and transit country. The destinations of women trafficked from or through Bulgaria vary, with Kosovo (Serbia), Macedonia and Western Europe most prevalent among them. Recently, the number of Bulgarian women trafficked has declined, possibly due to increased enforcement and a somewhat more stabilized economy. Bulgaria's NATO and current EU accession interests, as elsewhere in the region, have been influential in this process.

Since 1989, visa regulations have played an important role in the routes that traffickers use. Women from Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary did not need visas to travel to Germany and after their admission to the EU, they may travel more freely across its borders. Entrance into the EU, including candidate countries slated for admission in 2007 such as Romania and Bulgaria, has had a discernible impact on trafficking patterns. For example, the liberalization of visa requirements for Romanians traveling to EU member states has resulted in more women being trafficked to Western Europe than to locations in the former Yugoslavia. In this respect, EU accession facilitates trafficking within and across its internal borders in the short run, although anti-trafficking efforts serve as impediments. The efforts of the Southeast European Cooperative Initiative (SECI) Regional Center for Combating Transborder Crime are particularly noteworthy.

Western European countries are prime destination countries. Estimates of the numbers of women trafficked there vary widely. At the end of the 1990s Europol estimated that several thousand individuals were trafficked into the EU each year for the transnational sex industry and that 90 percent originated from Central and Eastern European states. In March 2001, according to an International Organization for Migration (IOM) report, the European Commission estimated that some 120,000 women and children were trafficked annually to Western Europe. The State Department has projected numbers between 600,000 and 900,000 of persons trafficked across borders. It is difficult to assess these statistics, however, because information about their collection is rarely detailed. Whatever the actual numbers, there is basic consensus about sending countries and the destinations of those trafficked. Not surprisingly, western destination countries tend to be wealthier than the Eastern European countries from which women's journeys originate.

Militarization also plays a role and has been a key feature in the diversification of trafficking in both Bosnia and Kosovo. Wars have facilitated trafficking—of women and girls, drugs and arms under the alleged auspices of competing mafias, traffickers and complicit, corrupt officials and individuals. Although Bosnia and Kosovo are comparatively poor, they have nonetheless become destination points: women from Moldova, Romania, Ukraine, and, to a lesser extent, from countries further east, such as Kazakhstan, often wind up in Bosnia. During the Bosnian war, the small town of Taszlar in Hungary saw the emergence of brothels with local and trafficked women in demand there. Within months of NATO intervention in the Kosovo war, a system of sex services was apparently flourishing. And soon after U.S. military planes began landing in Romania's Black Sea port city, Constanta, in February 2003, in preparation for the war in Iraq, the sex trade and traffic there increased.

Nonetheless, in general, trafficking occurs independently of militarization. As in other forms of labor migration, poverty and limited economic opportunities are primary factors in the lives of women and girls who are trafficked. According to the World Bank database of World Development Indicators, mid-1990s poverty rates in Eastern Europe were above 20 percent in some countries (e.g. Moldova, Poland and Romania) and above 30 percent in others (e.g., Russia and Ukraine). Although it is hard to find statistics on the rates of individual or family poverty that are comparable across countries, economic data from the UN and the World Bank suggest a relation between trafficking patterns and economic decline. Two primary source countries—Moldova and Ukraine—are also those with notably low Gross National Incomes (GNI). Moldova falls well below the cut-off point for being categorized by the World Bank as a "low-income country" with a 2002 per capita GNI of only $460; Ukraine barely made it above the $736 cut-off point with its 2002 per capita GNI of $770. Other sending countries, including Russia and Romania, are comparatively better off but are still classified in the World Bank's World Development Indicators Database as "lower-middle-income economies."

Women are disproportionately affected by poverty and limited economic options globally, including in post-socialist countries. For example, the World Bank's Gender Statistics Database showed increasing women's unemployment from 1995 to 2000 in the Czech Republic (4.8 to 10.6 percent), Poland (14.7 to 18.5 percent), Slovakia (13.8 to 16.4 percent), Russia (9.2 to 13.1 percent) and Ukraine (4.9 to 11.5 percent). Gendered labor market shifts have generally pushed women toward lower-paid and part-time work. Furthermore, rural poverty has grown dramatically since 1989; rural women are believed to be over-represented among trafficked women.

Given these trends, it is not surprising that women's unemployment rates tend to be higher than men's in primary sending countries such as Moldova and Ukraine. The exclusion of women from the paid labor force is an ongoing process in Ukraine, where gender specifications are a customary feature of job advertising and hiring, as are preferences based on marital status. Such gendered practices exclude women from some occupations, concentrate them in others, contribute to high poverty rates and unemployment for women, and leave them vulnerable to the enticements of traffickers who can take advantage of their desire for better working and living conditions abroad. To reiterate, women are recruited from both rural and urban areas (to which rural women have often first migrated). They need not be from among the poorest of the poor, or even from among the working poor. Whatever women's individual circumstances, their overall prospects are typically limited, making promises of their dreams coming true elsewhere adequate incentive to accept plausible offers from traffickers.

We underscore that trafficking forms part of forced labor migration as well as the global service economy into which women and children from the former socialist states have been incorporated. In view of politicized international attention to trafficking, it is often difficult to imagine that women and girls remain unaware of what may await them. And, hope of a better life in the much-fantasized West is a powerful incentive for many to take risks when they are assured of alleged job or marriage opportunities. Awareness is therefore an important factor in combating trafficking, as is cooperation between governmental and non-governmental organizations in promoting it. Engaging diverse means, including advertising campaigns, church sermons and educational programs in schools, can play an important role in enabling women to make better informed choices about opportunities and potential risks. Many such efforts presently exist. To illustrate, in Moldova, the government and the IOM have promoted a widespread campaign, using billboards and other media to advertise their message: "nu esti marfa" ("You're not a commodity").

But increased awareness will not eradicate trafficking. It does not combat poverty or limited job opportunities and economic prospects. Nor does it tackle the interests—and profits—that drive trafficking. International and country initiatives must address both ‘push' factors (e.g., poverty and gender discrimination in sending countries) and ‘pull' factors (e.g., the sex trade as a lucrative business for traffickers combined with ready underground sex markets in the West and across the globe), putting into practice the goals they have legislatively embraced.

Substantive and systematic research is also urgently needed which includes the development of strategies to produce reliable data on the number and demographics of women and children trafficked, detail their life experiences (through qualitative research), and analyze the relation between trafficking, prostitution, economic trends and militarization. Such information is crucial to better comprehend the dynamics and consequences of trafficking. Dialogue between specialists on migration and on prostitution must be promoted if trafficking is to be more fully conceptualized. There is presently little articulation between what are emotionally politicized and often moralizing discourses and debates about trafficking and actual practices. Given the fervor surrounding this multi-faceted issue, it is telling that research has not been at the forefront of strategies to address trafficking.

It is also telling—and paradoxical—that in the 21st century in which human rights discourses circulate widely across the globe, forms of slavery in the guise of trafficking are tacitly tolerated and, indeed, are proliferating. The interests that drive trafficking in women and children are intimately related to those driving other dimensions of trafficking, including of humans for forced labor other than sexual labor. As income disparities widen across the globe and as the service economy grows, it is ever more imperative that enduring gender inequalities in valuing women's work and recognizing women's rights be rectified. The persistent failure to do so contributes to the abusive trafficking patterns and conditions that so many claim to want to curtail. Until attention is focused on the demand side of trafficking (in all of its forms), and poverty is not a resource for profit-driven entrepreneurs the world over, trafficking will continue not only to exist but to expand.

About the Author

Gail Kligman

Director, Center for European and Eurasian Studies and Professor, Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe” – an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more