A blog of the Science and Technology Innovation Program

Dependencies in the US Semiconductor Industry

Promoting resilience does not require remapping global production from scratch. Investing in foreign partners—many of whom are already home to US firms and their subsidiaries—can maintain efficiency while still promoting diversification. The result would be more stable supply chains—and that means lower costs for producers and consumers.

The Wilson Center

Introduction

Persistent market shocks underline the fragility of critical supply chains. Of all critical industries, semiconductors have been one of the main areas of concern for the US government given their far-reaching applications in everything from mobile phones to missiles.

A common concern is overreliance on foreign suppliers. While the United States is home to many of the world’s leading firms, only about 11% of chips are made in the United States. The rest are imported from overseas, fueling concerns about supply shortages and motivating efforts to reshore production.

But supply chain vulnerabilities cannot be measured simply by how much the United States imports. The larger worries should be import concentration—that is, relying on too few suppliers—and how that concentration increases risk.

The following discussion offers two observations about these vulnerabilities and offers several suggestions for addressing unresolved risk.

Lots of Economies Produce Chips—but Very Few Provide the Inputs

Semiconductor production involves a wide range of activities spread across the global economy. US trade flows reflect this complexity. In 2023, 10 countries enjoyed at least a 5% share of total US semiconductor imports. Economies like Thailand, Taiwan, and Vietnam—none of whom ranked among United States’ top 10 sources of chips just a decade ago—have clawed away at a market recently dominated by China and Malaysia.

However, like many industries, production is far more concentrated at the early stages. An Organization for Economic Co-operation Development (OECD) study identified the raw materials and component parts in each sequential step, finding that twice as many countries sell finished chips to the United States than those who provide inputs. That’s despite the fact that there are more product lines considered to be “step 1” inputs (69) than “step 3” outputs (15).

Figure 1. Import Concentration by Stage of Semiconductor Production

| Step | # of Goods (6-digit HS) | # of Suppliers (Median) | Herfindahl Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Inputs | 69 | 23 | 0.26 |

| 2 Capital Goods | 20 | 74 | 0.13 |

| 3 End Use | 15 | 55 | 0.16 |

Concentration at the start of production is due mainly to the fact that only a few countries sit on top of—or refine—the necessary raw materials and commodities. A narrow set of countries provides platinum (South Africa), sulfuric acid (Canada), and graphite (China). In fact, there are 30 goods at “step 1” of the process where the US gets at least 50% of its imports from just one partner. There are zero goods at “step 3” with a similar level of concentration.

From that point of view, the vulnerability in the industry is not where the chips are made per se, but the fact that the process begins in a narrow set of countries who provide the inputs necessary for production.

Higher Import Concentration Means Greater Exposure to Volatility

Relying on foreign partners is not necessarily a bad thing. The United States depends on other countries in a wide variety of industries for mutually beneficial trade. The problem is that relying on too few partners makes it costly when disruptions occur.

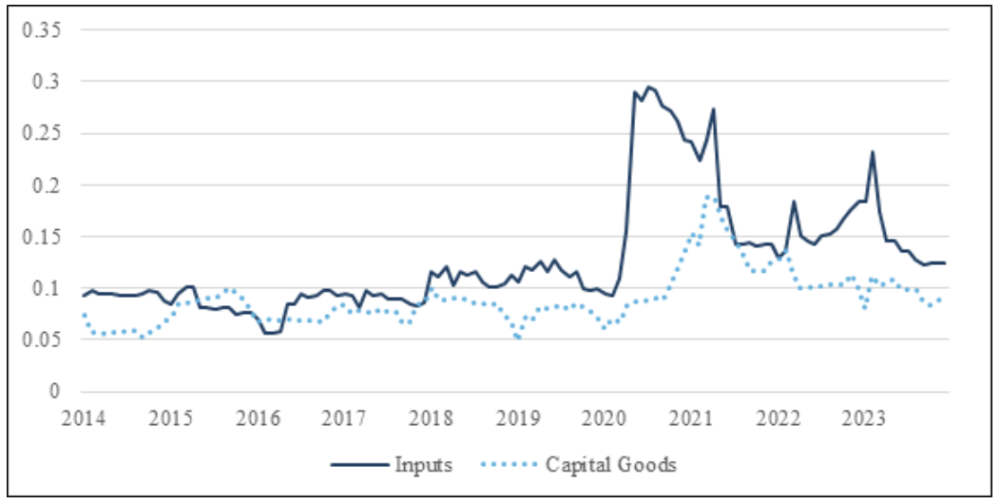

Unfortunately, semiconductor inputs are both more concentrated and much more volatile. Figure 2 shows that US imports of early-stage goods are 40% more volatile than intermediate parts and finished devices. Inputs were disrupted more significantly by the pandemic, and it took much longer for trade in those goods to revert back to normality.

Figure 2. Volatility in Semiconductor Inputs Trade

Jeffery Kucik

Notes. Graph shows the 12-month rolling standard deviation in monthly import changes. Higher numbers represent greater variation. Trade data is seasonally adjusted to reduce natural fluctuations in trade over the year. Inputs include chemicals, ores, and metals. Capital goods include wafers and other intermediate products.

That graph reports imports from all countries. But US trade with some countries is less stable than others. While the United States gets around 60% of its inputs from G7 partners, which are among the most stable trade partners, key imports from China are 11% more volatile than G7 members and imports from emerging markets like South Africa and India are 35% more volatile.

Taken together, those early-stage inputs, which come from fewer sources, exhibit far less stability. Recent history shows why that matters. Uncertainty over future supply dampens investment, diverts trade, and leaves consumers facing production shortages and price hikes.

Looking Ahead

The semiconductor industry has felt the negative impact of these vulnerabilities already, having lived through recent years of persistent disruption. However, current policy solutions focus narrowly on reshoring production while largely ignoring the benefits of investing abroad. In addition to domestic initiatives, the US must also try to strengthen partnerships with those foreign suppliers in ways that can help address unresolved risk.

Invest in capacity abroad. The United States’ principal development lender, the Development Finance Corporation, is already involved actively in lending to infrastructure projects across Asia. But it could be doing more, in conjunction with the semiconductor industry, to coordinate investments in emerging and developing market capacity.

Reboot trade agreements. Evidence shows that trade agreements do at least one thing very well—reduce volatility among member economies. With the failure to conclude the core trade pillar under the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, and with other commitments “on pause,” the United States unit must consider deals that would help lock in relationships to spur investment.

Ultimately, promoting resilience does not require remapping global production from scratch. Investing in foreign partners—many of whom are already home to US firms and their subsidiaries—can maintain efficiency while still promoting diversification. The result would be more stable supply chains—and that means lower costs for producers and consumers.

Note: The analysis here relies on the harmonized system codes identified on the International Trade Administration’s critical supply chain list along with trade data from the US Census Bureau’s USA Trade Online utility. All calculations by the author unless otherwise referenced.

About the Author

Jeffrey Kucik

Associate Professor in the School of Government and Public Policy and the James E. Rogers College of Law, University of Arizona

Science and Technology Innovation Program

The Science and Technology Innovation Program (STIP) serves as the bridge between technologists, policymakers, industry, and global stakeholders. Read more

Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition

The Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition works to shape conversations and inspire meaningful action to strengthen technology, trade, infrastructure, and energy as part of American economic and global leadership that benefits the nation and the world. Read more