A blog of the Polar Institute

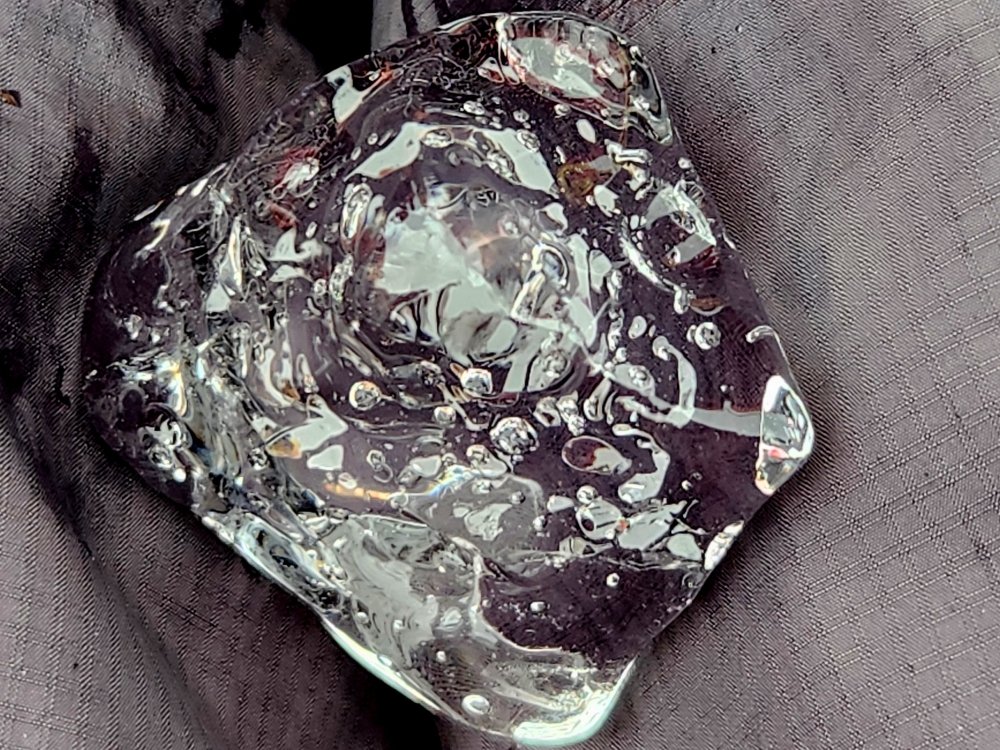

On my trip through the Arctic this summer, en route to the North Pole, I picked up a drifting bergy bit during a zodiac ride across the icy waters. Bergy bits are chunks of ice that break off disintegrating icebergs. They can be large, several feet in size, or very small, measured in inches, like the one I deposited in my lap to photograph against my black waterproof pants. The bergy bit looked like a piece of transparent amber—only the little flecks were air bubbles, not bugs. “The air in that bergy bit has been trapped since before the time of Christ,” an expedition expert told us. As bergy bits melt, they make a snap, crackle and pop sound—just like the cereal. I watched helplessly as the melting bergy bit in my lap unleashed air from more than two millennia ago.

I witnessed both the agony and the ecstasy of the mystic Arctic landscape during the three-week expedition on a French icebreaker. On another zodiac ride miles from the ship, we came close to a massive aqua iceberg that had broken off a glacier—a process known as calving—just two days earlier. “Iceberg” literally means “mountain of ice;” berg is borrowed from the German for “mountain.” The iceberg in front of us had towering ridges and looked like a large chunk of Manhattan, complete with sky-high high-rises.

Icebergs are stereotyped as white, but more often I’ve seen them in both the Arctic and Antarctica shimmer in shades of sapphire, sparkle in subtle tones of jade, or even flash in emerald hues. Their colors depend on the interaction between crystallized snow and light. They can even occasionally appear yellow or red, depending on interaction with sea life or iron-rich minerals. Every iceberg has a unique shape too; they can appear neatly carved or rough-hewn, serrated or stripped, lumpy or artistically embossed. One facet of the iceberg we happened upon that day had a recess that made it look like the entrance to an elegant cathedral. As we headed back to the ship, we heard the roaring thunder of other icebergs calving from glaciers. As Coleridge wrote in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,

“The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound!”

Icebergs sever when glaciers become unstable or stressed and shear off large chunks into the surrounding waters. The process can reflect the cycle of nature, since glaciers move over eons of time, tugged by their weight and gravity, toward the sea. But the phenomena also illustrate the repercussions of a warming climate. Roughly 10 percent of Earth is covered by glacial ice—and more than 80 percent of those glaciers could melt by the year 2100 if current trends in climate change continue apace, according to a study last year in Science magazine. Glaciers recede by up to 10 meters, or 32 feet, a day, Christian Haas, director of the Sea Ice Research Group in Germany, explained on our expedition. One day, when we were both on deck, he pointed out two glaciers that — just five years ago — had been one. For some glaciers, it’s already too late. We saw glacier melt on several days.

The eerie reality of the Arctic was visible again on an excursion to the shoreline of a receding glacier. The thin strip of gritty sediment had never been seen by humans until this summer, Anna Lena Ekeblad, an expedition specialist who lives in the Arctic, explained. The glacier had covered the slope since before the emergence of our species. Glaciers can have lengthy lifespans — up to a million years or more, according to the U. S. Geological Survey. By contrast, humans—meaning a “culture-bearing, upright-walking” species—probably evolved some three hundred thousand years ago, scientists and zoologists contend.

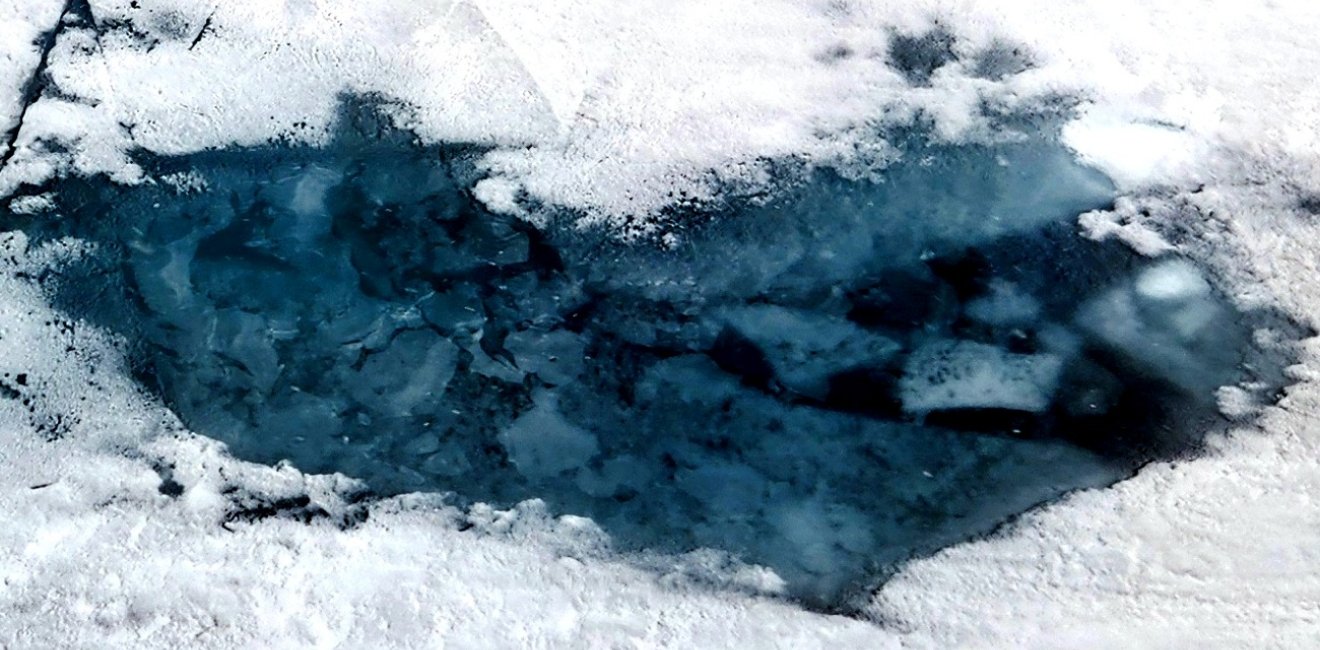

The Arctic is now melting faster than anywhere on Earth, evident even at the North Pole. I got off the ship to navigate among melting ponds, which are pools of either sea ice or glacier ice—and they are different—more prevalent in summer months. Glacier ice is formed from freezing fresh-water snow, while sea ice is from the frozen salty water of an ocean. They don’t mix because they have different density and salinity. The North Pole had dozens of melting ponds across the horizon.

Melting ponds hold both allure and danger. They have various hues of blue, from soft turquoise to midnight blue. The darker the blue, the deeper the water. I walked through a few of the soft aqua ponds, but the depth can be an illusion. We dubbed one the size of a small lake the “Blue Lagoon.” No one dared test its bottom. All of the passengers and crew who disembarked at the pole were required to wear life jackets over our bulky red coats—for good reason.

The proliferation of melting ponds across the Arctic was among the most surprising spectacles, even for our expedition experts. During the summer, the world’s northernmost region experiences a polar day, when the sun is perpetually up for months. It’s still freezing, however. The wind hit 28 knots on our second day at the North Pole. Yet melting ponds were as striking as the snow and ice at the pole on a blustery cold day.

I sailed to the North Pole on Le Commandant Charcot. It was named for the great polar explorer and scientist Jean-Baptiste Charcot. “Where does this strange attraction of these polar regions come from, so powerful, so tenacious?” Charcot poignantly wrote after one of his voyages. “Here, it is the sanctuary of the sanctuaries, where nature reveals itself in its formidable power…The man who has been able to enter this place feels his soul rising.” Woman, too.

After leaving the North Pole, we witnessed other aspects of Earth’s changing ecology en route to Svalbard, the Arctic archipelago north of Norway. On one excursion, we encountered several gushing waterfalls cascading from a thawing glacier down a mountain of raw dolomite. A remnant of the glacier was barely visible at the top. The sight was a harbinger, both breathtaking and haunting, about Earth’s future.

The last stop on our Arctic expedition was at Gnålodden ont the southern tip of Svalbard. It is a mossy tundra rich with birdlife—thousands of kittiwakes and guillemots—nesting among towering crevices. The noisy birds were a cheery change from the deafening silence of the ice. But as I headed home, I was also struck by T.S. Elliot’s reflection in Four Quartets, his collection of poems meditating on the human species’ relationship with time, the universe and the divine. He rightly opined,

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

Author

Polar Institute

Since its inception in 2017, the Polar Institute has become a premier forum for discussion and policy analysis of Arctic and Antarctic issues, and is known in Washington, DC and elsewhere as the Arctic Public Square. The Institute holistically studies the central policy issues facing these regions—with an emphasis on Arctic governance, climate change, economic development, scientific research, security, and Indigenous communities—and communicates trusted analysis to policymakers and other stakeholders. Read more

Explore More in Polar Points

Browse Polar Points

In Search of Polar Bears in the Arctic Summer: Part I

In Search of Polar Bears in the Arctic Summer: Part II

Greenland’s New Governing Coalition Signals Consensus