A blog of the Kennan Institute

To receive an email when a new post becomes available, please subscribe here.

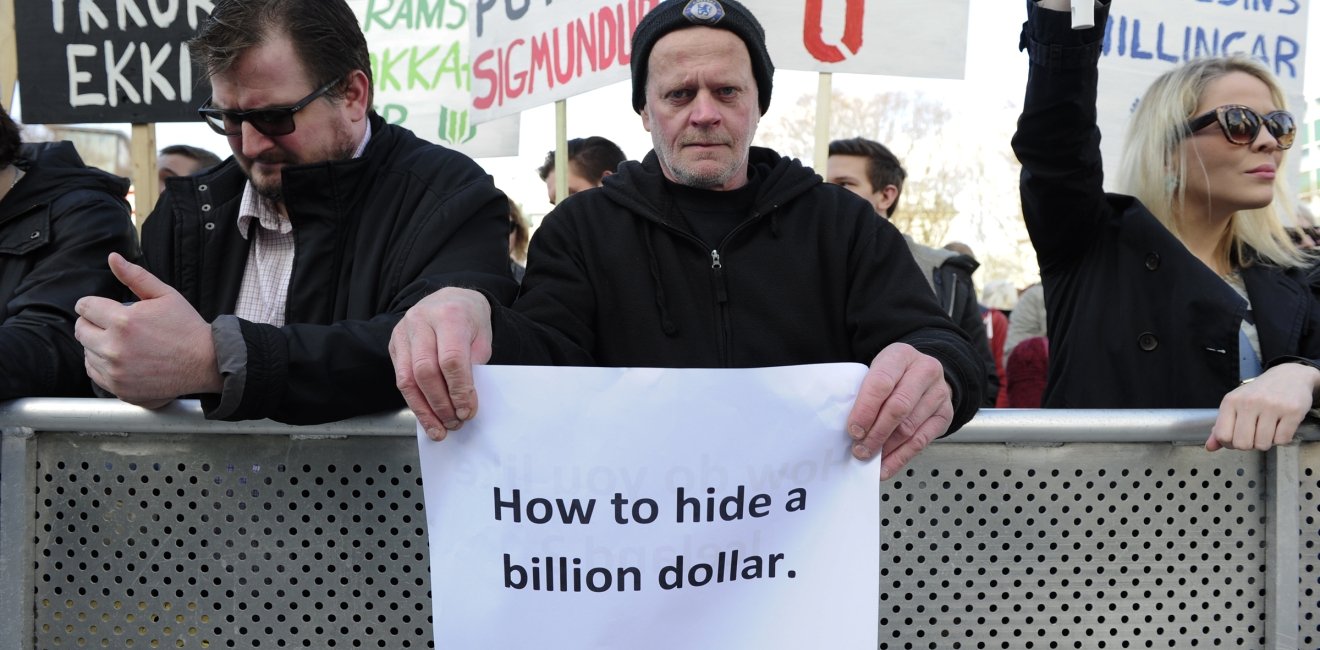

The so-called Panama Papers are unlikely to make a huge difference in today’s Russia. Reports based on the papers, a large trove of documents currently under scrutiny by journalists and public authorities throughout the world, are causing some controversy, but not a revolution. Many in Russia are used to seeing elites park their spoils abroad; it’s perceived as an act of prudence, not as a crime. At least for the time being.

The story illuminated by the Papers that attracted the most interest in Russia was that of Sergey Roldugin, a recognized cellist, Russian People’s Artist, professor and lifelong friend of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Roldugin’s alter-ego, investigators allege, is as “secret caretaker” of the Kremlin. According to Roman Anin, Olesya Shmagun, and Dmitry Velikovksiy of the OCCRP, Roldugin controlled (either directly or indirectly) a group of affiliated companies that usually did one of three things: dubious over-the-counter transactions with shares of the largest state-owned Russian companies such as Rosneft; received “donations” from major Russian businessmen often laundered through paper deals; received preferential loans from the Cyprus-based RCB Bank, a large stake of which is controlled by the Russian state-owned VTB Bank.

Many in Russia are used to seeing elites park their spoils abroad; it’s perceived as an act of prudence, not as a crime. At least for the time being.

Russian officials referred to the reports as an information attack. Although Vladimir Putin is not personally mentioned in any of the leaked material, Putin's spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, suggested that the reports were the result of "Putinophobia" and aimed at smearing the country in a parliamentary election year. “Putin, Russia, our country, our stability, our coming elections are the main targets,” Peskov said.

Even State-run television did not ignore the news and ran a segment titled “Scandal Arrived from Panama,” complete with a quote from Gerard Ryle who leads the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) headquarter staff in Washington, D.C., and oversees the consortium’s 190 member journalists in more than 65 countries. “People close to Vladimir Putin are mentioned in connection with the leak,” the report on Russia’s Channel One said. “But no confirmed cases of wrongdoing have been reported.”

The audiences of the Russian state-run television have a long history of living in a separate media universe, in which Western news and opinions have little meaning.

The Panama Papers material is reported to have been leaked to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung from the database of Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian offshore law firm. Two consortia of investigative journalists worked on the project: The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). ICIJ is funded by private donors and makes a point of not accepting U.S. government funds. The OCCRP is partly funded by USAID.

Russia’s political managers anticipated the news of the investigation because they received questions from the reporters working on the story. A few days prior to the publication, Peskov called it “an information plant” (информационный вброс). The Kremlin did not seem to be particularly upset by the investigation. Media policymakers knew they would have little trouble diverting the attention of the majority of the population and giving the right spin to all the rest. The audiences of the Russian state-run television have a long history of living in a separate media universe, in which Western news and opinions have little meaning. Even the fact that the Panama Papers are called “a leak” is convenient to Russian politicians.

A good example is Putin’s spokesman Peskov himself, who (through his wife) is mentioned in the trove. According to the reports, Peskov’s wife, the professional figure skater Tatiana Navka, registered an offshore firm in the British Virgin Islands in 2014 and dissolved it in 2015. Both Peskov and Navka denied the existence of this firm. “My wife does not and has never owned any offshore companies. Based on this I am inclined to doubt the authenticity of other claims,” Peskov said to reporters.

Subjects of investigations by independent Russian journalists and foreign media often suggest that the material was “leaked” by ill-meaning political rivals and, of course, foreigners (oblivious to the contradiction in their own logic: if it’s “leaked,” it could be true). A leak is not seen by the general public in Russia as a piece of information that requires checking, but rather a result of manipulation, a piece of false evidence planted by someone. People tend to think that all business is murky and all politics are dirty, and yet another leak does not change their overall perception. Years of watching state-run television, with its hundreds of crime shows and reports of world-wide conspiracies, taught Russian citizens that facts can be subject to manipulation and the truth, in the end, is unknowable. This is why there is no point in Kremlin trying to hide the report.

For the Russian public (or the part of it that is aware of the leak) the Panama Papers only prove the obvious: it is simply not safe to keep funds in Russia.

Moreover, the use of foreign jurisdictions is not seen in Russia as a major transgression. In most cases it is not illegal. Public officials and Duma deputies are banned from keeping accounts in any foreign countries, not just offshore zones. But even officials using offshore shell companies are not condemned by many Russians. The general perception is that this is the way things are. The use of offshore havens may be a violation of some laws or rules, but it is not seen as violation of informal norms of accepted business practices.

Paradoxically, Russia’s business community has never really championed private property rights in any substantial way. Most businesses have long been registered in offshore jurisdictions, most entrepreneurs have long ago acquired foreign residency permits, and their money has been parked abroad. For the Russian public (or the part of it that is aware of the leak) the Panama Papers only prove the obvious: it is simply not safe to keep funds in Russia. Formal rules are perceived as only part of the story and usually not the most important one. There is an understanding that tax evasion is not the main reason for Russia’s endemic jurisdiction flight. The main impetus is simply cleverness. The Russian society may have become resigned to thinking that their country is not able to provide the kind of institutional framework that is needed to keep ones assets safe. The institution of private property in Russia is highly dependent on legal regimes of the very countries the Kremlin loves to proclaim as enemies.

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the author.

Author

Editor-at-Large, Meduza

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship