This project analyzes production and employment systems in selected fruit and vegetable commodities that are exported from Mexico to the US, develops statistically reliable data on the wages and working conditions of hired farm workers in selected commodities and a qualitative research strategy to understand farm workers and their families and the supply chain, and makes recommendations to increase worker protections in Mexico's export-oriented agriculture.

A workshop October 15, 2018 at the Wilson Center in Washington DC reviewed the worker data collected in a pilot survey of farm workers, learned what employer associations and certification organizations are doing to ensure compliance with labor laws on Mexican farms that export produce, and heard expert assessments of the likely effects of newly elected President AMLO on rural Mexico and farm workers.

The US imports a rising share of its fresh fruit and vegetables, and Mexico is the leading supplier of imported fresh fruit and vegetables. In 2017, the US imported $13.3 billion worth of fruits and vegetables from Mexico, which was almost half of total US fruit and vegetable imports and over half of US agricultural imports from Mexico.

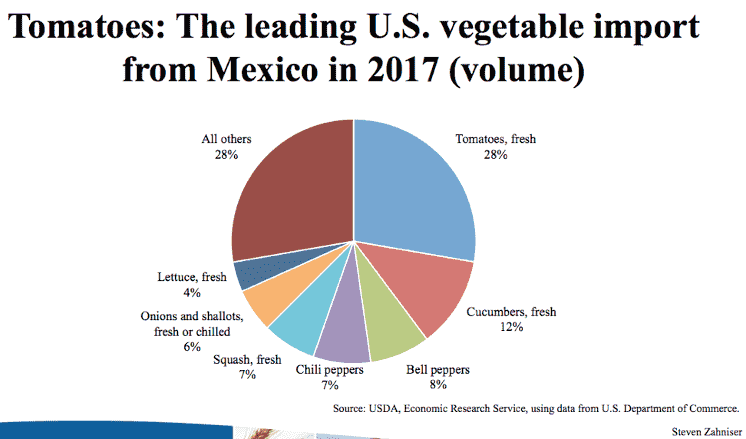

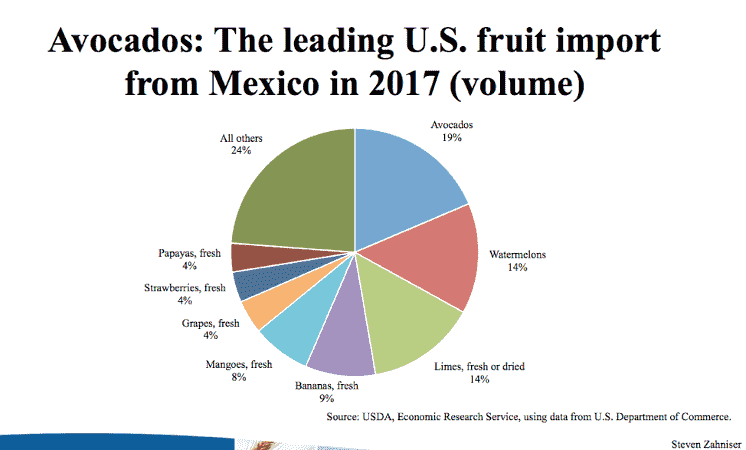

Mexico's growth as a supplier of US fruits and vegetables is due to demand factors in the US and supply factors in Mexico. Americans want fresh fruits and vegetables year round, and Mexico has the climate and infrastructure to provide them, especially during the off season in most of the US between January and April. Avocados and berries are the leading fresh fruit imports from Mexico, worth $3.4 billion or two-thirds of fresh fruit imports in 2017, while tomatoes, cucumbers, and bell peppers are the leading vegetable imports, worth $2.8 billion or half of fresh vegetable imports.

Mexico provides most of the avocados and raspberries consumed in the US year round, and most of the fresh tomatoes, cucumbers, and bell peppers consumed in the US during the winter and spring. The integration of the North American fresh produce industry reflects free-trade policies, US and Mexican investment in protected culture or plastic covered hoop structures that reduce disease and pest pressures while improving food safety, and an efficient trucking and transportation infrastructure.

There are seven million people employed in Mexican agriculture, 88 percent men. Most self-employed and most have no job-related benefits (IMSS and Infonavit). The largest numbers of self-employed farmers and family members are in the southern states of Chiapas, Guerrero, and Oaxaca.

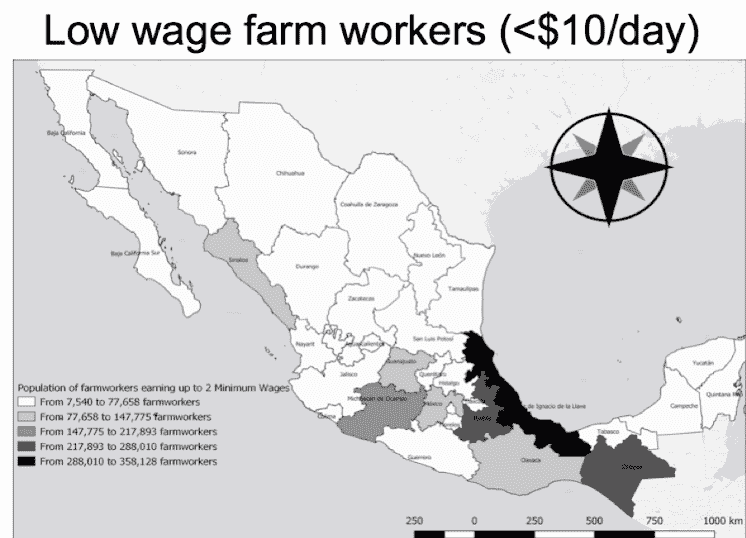

Some 36 percent or 2.5 million of those employed in agriculture are wage workers, and most of these hired workers are in states such as Veracruz that produce for the Mexican rather than the export market. The states with the most higher wage farm workers, those earning over $15 a day and with IMSS and Infonavit benefits, are Jalisco and Sinaloa, major fruit and vegetable exporters. The states closest to the US, Baja California, Baja California Sur, and Coahuila, had almost half of all hired farm workers registered for IMSS and Infonavit benefits.

INEGI data show that the highest percentage of family farm workers who do not receive wages are in Chiapas, Oaxaca and Guerrero. Hired farm workers with the lowest wages are in states along the Gulf of Mexico, Campeche, Tabasco, and Veracruz, where over 58 percent of farm workers earn less than two minimum wages (176 pesos or $9.50 a day). The largest number of farm workers earning above three minimum wages (264 pesos or $14 a day) are in Jalisco, Michoacán, Sinaloa and Sonora.

The rural poverty rate of about 55 percent is significantly above the urban poverty rate of 35 percent. However, the rural poverty rate has been falling faster as the real wages of farm workers rise, with a data anomaly for 2014. The growth of Mexico's export-oriented agriculture may be accelerating a reduction in rural poverty.

We analyzed a 2018 survey of 4,500 berry workers and did a pilot survey of over 100 workers in Jalisco and Michoacán. There are four tentative findings:

- First, farm workers perceive export oriented agriculture to be different from traditional agriculture. Many workers distinguish ”good” farm jobs in protected culture structures that produce berries and vegetables for export from “bad” farm jobs in sugarcane and other traditional crops.

- Second, about 80 percent of hired or wage workers in export-oriented agriculture have IMSS and Infonavit taxes paid on their behalf, far higher than the 45 percent of all Mexican workers whose employers make contributions to these programs. Some farm and nonfarm employers do not pay the full taxes owed, reporting that their employees earned only the minimum wage instead of the two to four minimum wages they actually received. Less-than-full payment of payroll taxes may be related to the failure of IMSS and Infonavit to provide significant benefits to workers, especially to migrant workers, which encourages employers to save money by underpaying without generating complaints from workers.

- Third, export-oriented agriculture is changing to offer more year-round or permanent jobs, which reinforces other trends encouraging migration from south to north within Mexico. Most hired farm workers have not completed secondary school. As the pool of such workers near export-oriented farms decreases, growers are recruiting more migrants from poorer mountainous areas and southern states. Some of these migrants are settling near their jobs, so that export-oriented agriculture is reinforcing other factors that move Mexicans from south to north. The settlement of especially indigenous and non-or limited-Spanish speaking workers and their families may lead to tensions in some local communities if governments fail to provide services to these new residents.

- Fourth, the farm workers employed in export-oriented agriculture appreciate the flexibility of most farm employers. Many farm worker families have one or more members suffering from chronic illnesses, so that one member of the family may not be able to work or can work only part-time. Farm employers are more likely than nonfarm employers to accommodate flexible schedules for such workers.

Major exporters and their associations are well aware of the challenges involved in obtaining workers for their expanding industry. Marketers with brands to protect have developed codes of compliance and conduct for their suppliers that are enforced by third-party auditors, showing industry interest in protecting the workers employed on exporting farms.

Associations representing growers and marketers have an ethical charter to encourage growers to support the dignity of farm workers throughout the supply chain (www.ethicalcharter.com). Growers are encouraged to comply with applicable laws and regulations, to ensure that migrant workers are recruited ethically and without discrimination, and to respect the human rights of their workers. Buyers are expected to reinforce the charter by purchasing from compliant growers.

Marketers and associations have experience bringing farms into compliance with their expectations, as demonstrated by the adoption of a culture of food safety during the past decade that has made imported produce as safe or safer than US-produced fruits and vegetables. The goal of AHIFORES is to maintain the focus on food safety and to develop a similar culture of protecting and respecting farm workers, making conditions for farm workers as world-class as the fruits and vegetables they help to produce.

AHIFORES has three priorities for the new Mexican government, viz, allowing 16 and 17 year olds to work in export-oriented agriculture in some jobs, increasing employer compliance with payroll tax obligations and persuading government agencies to offer more services to covered workers, and improving protections for internal migrant workers who are recruited by contractors.

EFI and Fair Trade USA often go beyond buyer requirements and association guidelines and require certified farms to educate workers about their rights and responsibilities and to form farm-level teams to monitor compliance with labor laws and to deal with complaints of violations. Farmers generally pay for certification if they (1) fulfill most of the requirements and (2) believe they will have better access to preferred buyers and/or receive higher prices for their products.

Both EFI and Fair Trade USA collect small premiums from some of the buyers of fruits and vegetables purchased from certified farms. Some of these premiums are returned to workers as bonuses, while others are pooled for community projects selected by workers.

Reports of worker abuse in Mexican agriculture, especially articles in the LA Times in December 2014, make Mexico a major growth market for EFI and Fair Trade USA, certifying organizations have more farms certified in Mexico than in Canada and the US. Along the spectrum from unions and collective bargaining agreements at one end to government laws and regulations at the other, certification is an in-between option to protect farm workers, chosen by the employer rather than the employees but aimed at protecting workers and appealing to buyers and consumers.

The farm labor landscape may change under President AMLO, a symbolic politician with a genuine concern for rural poverty but without a clear strategy to reduce it. AMLO has promised infrastructure projects in southern Mexico to better integrate these poorer states into the rest of Mexico, plans to plant trees to provide jobs in rural areas from which youth may otherwise emigrate, and renew efforts to help smaller farmers become viable. AMLO has made youth a special priority and wants a million manufacturing internships to ease the school-to-work transition; it is not clear if export-oriented agriculture will be included in the internship program.

Many of AMLO's advisors are advocates, and some are skeptical of export-oriented agriculture, citing concerns that range from exporting scarce water in fruits and vegetables to creating “bad” jobs that attract hard-to-integrate internal migrants to the major production areas. Export-oriented agriculture is often criticized for environmental damage, as with pesticides and plastics. Some of AMLO's advisors see export-oriented agriculture as another example of foreigners generating profits from Mexican resources and people.

These perceptions are not borne out in our preliminary survey and case study work. Most people employed in export-oriented agriculture are local, although the share of migrants is at least 25 percent and rising. Internal migration to export-oriented agriculture reduces poverty by moving poor people to higher wage jobs. Since most export-oriented farms enroll their employees in IMSS and Infonavit, the challenge is to encourage the government agencies that collect taxes in order to offer health care, pension, and housing benefits to migrant farm workers so that health and housing do not become an issue for farmers and local communities.

Important segments of export-oriented agriculture are in West Central Mexican states such as Jalisco and Michoacán that sent large numbers of migrants to the US. Some of the children and grandchildren of US-bound migrants are finding jobs on export-oriented farms, making it unnecessary for them to migrate illegally to the US. In a very real sense, some export-oriented farm jobs are a substitute for migration to the US.

Mexico's export-oriented agriculture may be at a crossroads. Mexican produce has won acceptance for quality and safety in the US. Turning agriculture from a source of seasonal jobs accepted by those without other options into permanent careers selected by workers with other options has been the quest of many agricultural systems. Mexico's export-oriented agriculture may provide a test of whether agriculture can be associated with life-long careers rather than short-term jobs.

Below are selected figures from the October 15, 2018 presentations

Authors

Professor, CIESAS Occidente; Director, Jornaleros en la Agricultura Mexicana de Exportación

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Water Security at the US-Mexico Border | Part 1: Background

China and the Chocolate Factory

Ongoing Debate: The Prohibition of GMO Corn in Mexico