Rwanda’s Paul Kagame is accustomed to accolades. On May 12, he received yet another honorary degree, this time from William Penn University in Oskaloosa, Iowa. Celebrating Kagame is in vogue because he is credited with leading a remarkable recovery from war and genocide in the heart of Africa.

There certainly have been achievements in Kagame’s Rwanda. Economic growth has been climbing (G.D.P. growth for 2011 was more than 8 percent) and private investment is a featured component of that growth (Costco and Starbucks now buy about a quarter of Rwanda’s premium coffee crop).

In fact, the World Bank ranks Rwanda as the eighth easiest place to start a new business. The government is renowned for reducing corruption, expanding security, addressing genocidal crimes and increasing women’s rights.

Yet while Kagame is no Idi Amin or Charles G. Taylor, he does not merit his reputation as a visionary modernizer. The reason is simple: his state is all about force.

There’s no question who’s in charge in Rwanda. The government’s commanding presence in Rwandan lives is aggressively maintained by Kagame and a clique of other former Tutsi refugees from Uganda. Indeed, according to the U.C.L.A. sociologist Andreas Wimmer, Rwanda has the third-highest level of political exclusion in the world (behind Sudan and Syria).

Kagame’s government asserted its power in the run-up to the 2010 presidential elections, when authorities barred most opposition political parties from registering for elections, closed down many independent newspapers, and witnessed the flight into exile of several prominent government officials who said they “feared for their lives.”

There were also three suspicious pre-election shootings. One of the exiled officials, Kagame’s former chief of staff, Faustin Kayumba Nyamwasa, was shot in the stomach in South Africa after openly criticizing the Rwandan government. A Rwandan journalist, Jean Léonard Rugambage, was killed shortly after his article, which pointed to government complicity, was published. The deputy leader of the Green Party, which was among those unable to register, was found not only dead but with his head partly severed.

Kagame garnered 93 percent of the vote. Soon after the election, an exhaustively researched United Nations “mapping exercise” report led the veteran Rwanda expert Filip Reyntjens to state that “there is overwhelming evidence of responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity” against Kagame. A foreign expert (who asked not to be named) also reported the disappearance of “a large number” of Rwandan civil society members in 2007.

Nowhere is the heavy-handed and destructive nature of Kagame’s government more apparent than in its approach to youth. In Rwanda, traditionally no young man can be recognized as an adult until he first builds a house and then marries. But my research detailed how government regulations make it virtually impossible for young Rwandans to complete their houses.

It is not just that forcing farmers into state villages has consistently failed across the region (notably Ethiopia, Tanzania and Mozambique). A government official also explained that, although most young men are able to construct a dwelling consisting of “one simple room,” the government’s minimum required dimension is six times that size. The result is a treadmill toward public humiliation.

The specter of masses of failed men is no small concern: with a median age of 19, Rwanda has one of the youngest populations in the world.

The alarming situation that Kagame’s government has created boils down to this: While government officials are expected to implement policies that cannot be enacted and dissent is out of the question, people are being forced to follow a blizzard of regulations. Lacking options, desperate Rwandans become lawbreakers, building illegal houses that the authorities tear down and enduring fines and harassment by selling wares in the streets.

The government’s response is to pressure people even more. As Kagame explained to the journalist Stephen Kinzer, “We have to work on the minds of our people. We have to take them to a level where people respect work and work hard, which has not been the case in the past. You have to push and push.”

My research found the reverse: most Rwandans are stuck in difficult and frequently humiliating circumstances, which government regulations have largely created. Mid-level Rwandan officials confirmed every major finding.

Envisioning a radiant Rwanda is only possible if one shares the blinders that its government so confidently wears. The government of Paul Kagame boasts many excellent ideas. But underneath the splendid success are disturbing realities that are systematically contained. At least for now, Rwanda’s progress is dangerously uneven and so reliant on extreme levels of social and political control that its future is foreboding.

Despite its promise, Rwanda is a country in lockdown. Loosening the autocrat’s reins and helping his nation avoid another violent explosion is a message that only Rwanda’s international supporters can deliver to President Kagame. Foreign governments and individuals alike must push for easing or removing restrictions on the press, politics, civil society, housing, street vending and much more. Advocating against state coercion is far too dangerous for Rwandans themselves to undertake.

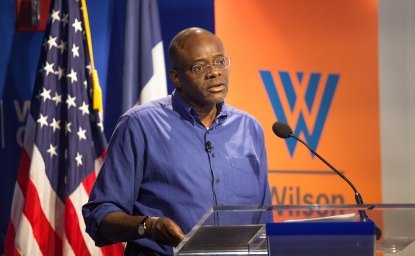

Marc Sommers is a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the author of “Stuck: Rwandan Youth and the Struggle for Adulthood.”

This op-ed was first published in The New York Times.