A blog of the Kennan Institute

BY MAXIM TRUDOLYUBOV

When we see Russians debate hot public policy issues—right now a controversial pension reform and the arbitrary rule of security agencies—it is useful to remember one crucial statistic. The majority of those polled consistently respond that they are unable to influence any decisions the Russian state makes.

A lot of people in Russia also think that the state should maintain generous social policies. From these two premises—they cannot affect political outcomes, they expect support—the conclusion is often drawn that Russia has a strong state and a weak society in which most citizens’ behavior is driven by some operant notion of paternalism.

In fact, the opposite is true: 94 percent of those who answered the question said they placed reliance in themselves only, a recent focus-group study found. Just six percent said they were expecting the state to support them. Regular opinion polls confirm these results: historically, between 74 and 80 percent of those polled responded that they relied exclusively on their own and their family’s resources in life, not on the state or any other source of support.

This is how people phrased their attitudes during the series of focus groups cited above: “No happy tomorrow for us. It’s not going to happen, there is no hope, you have to change, you have to change your life.” “Slave mentality is the whole problem. While the majority swallows it and is ready to endure even more, nothing is going to change. Putin or no Putin, it’s not that important.” “If everyone works to change themselves we will be better.”

This does not sound like people who are expecting a higher force to help them. By various estimates, from 30 to 48 million people in Russia work in the so-called unobserved sectors of the economy (Russia’s total workforce is over 70 million people). Almost half of Russia’s population fends for itself and does not expect any social support or any pension to speak of. More than 60 percent of those polled said they avoided any contact with Russia’s political power.

Millions of people live outside the domain of the law and government institutions, the sociologist Simon Kordonsky said in a recent interview. “We have two normative systems: the official one, which is built around the written law, and the second one, which is informed by the quasi-law called poniatia [literally “notions,” meaning a code of mutual understanding]. The two systems operate within the same space, within the same people. People are split within themselves: they live according to the poniatia but interpret other people’s behavior according to the law. Everyone is breaking the law, they often conclude,” Kordonsky said.

People in Russia do want the government to pay them a pension and provide other social services, but they do not rely on the state for their livelihood. A pension is good to have, it is fair, but it is not crucial. After the news of the retirement age being increased people may even take to the streets in protest, but that does not mean a true rebellion will necessarily grow out of it. And it is not just because the authorities prevent real social movements from developing by manipulating the masses.

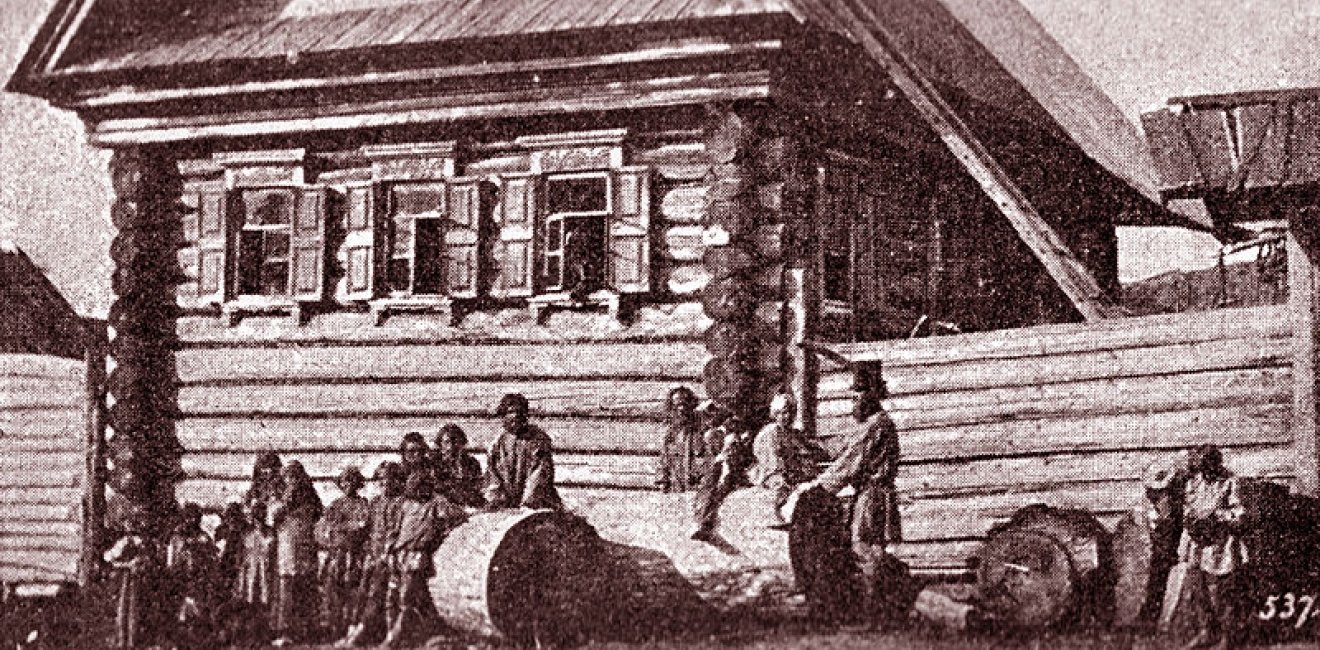

It is because most Russians believe they will extract at least something from the state by using its resources, by avoiding taxes, or by otherwise taking advantage of it. Russians look at their state as if from a distance, a safe distance. The feeling of being separate from the state is an ingrained feature of Russian life. It may go back to the attitude of the Russian peasantry to the imperial state of old.

“Three Soviet generations were not enough to kill off the rural streak in the citizens of the formerly great peasant power,” said Alexander Nikulin, head of the Center of Agrarian Studies at the Academy of National Economy. “We see the fragments of the former peasant worldview in the ways people tend to their country plots of land, to their dachas. We see the lifestyle of a people who are atomized, powerless, deprived of any real self-rule or communal cooperation.”

The techniques Russians use to evade and passively resist the policies imposed on them by the state may be compared to the way peasants always responded to government policies, as described by the anthropologist James Scott in his book, Weapons of the Weak.

The majority’s relations with the state could be likened to the kind of social contract that once existed between peasants and centralized states everywhere, not just Russia. Peasants carry out labor obligations and provide urban communities with the fruits of their hard work, they profess loyalty to the government (hence Putin’s famous approval rating, right now going down but still strong), they serve in the army, they put up with being assigned a lower station in the social hierarchy, but they expect certain things in return, Nikulin says. They expect the state to maintain public order and provide some social guarantees to them.

With more than 80 percent of the Russian population being rural at the beginning of the twentieth century, most Russians, including this writer, are two to four generations removed from their peasant ancestors. It is a complicated question whether the attitudes of today’s Russians could be attributed to peasant culture. More likely, these attitudes are reproduced in a society that feels powerless and separated from political institutions people cannot relate to.

Russians do realize, of course, that they have little role in helping the current rulers and legislators to power. Those who have not written the rules can easily disregard them. That is the case today just as it was yesterday, during the Soviet era. The fact that most Russians resort to the weapons of the weak does not mean that the state they continuously outsmart can be considered strong.

The state pension is one of those tiny, meager things Russians feel they are owed because they have suffered their fair share of trouble inflicted by the state. They have worked hard. Some of them have toiled on the state’s payroll and some have survived in what the state calls the “shadow economy”; people do not really see the difference. What they know is that they have fended for themselves and have not interfered with the state’s unexpected mobilizations or modernization initiatives. They do prefer adequate compensation, but what they want even more is to remain half-hidden or even completely hidden from the prying eyes of the state.

Author

Editor-at-Large, Meduza

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship