The changing nature of digital trade, current and future barriers and ideas to overcome them

The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the authors and do not represent the official views of the OECD or of its member countries.

The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the authors and do not represent the official views of the OECD or of its member countries.

The digital transformation has led to unprecedented reductions in the costs of engaging in international trade, changing both how and what we trade and contributing to growing competitiveness (Lopez-Gonazalez and Jouanjean, 2017)[1] and (WTO, 2018)[2]. However, as a result of the digital transformation, trade has become more complex, and how and which measures affect trade has also changed (Lopez-Gonzalez and Ferencz, 2018[3]). Old issues such as trade facilitation have new meaning in the digital era where more small parcels cross international borders, and new issues such as cross-border data flows can raise new challenges. In today’s rapidly evolving digital environment, governments are facing growing regulatory challenges in ensuring that the opportunities and benefits from digital trade, for both individuals and for businesses, can be realised and shared more inclusively.

Digital trade involves digitally enabled or digitally ordered cross-border transactions in goods and services which can be digitally or physically delivered (Lopez-Gonzalez and Jouanjean, 2017[1]). In much the same way that reductions in transport and coordination costs enabled the fragmentation of production along global value chains (GVCs), declining costs of sharing information are helping reduce barriers to engaging in international trade leading to:

Countries with a higher degree of internet penetration have a greater degree of trade openness and sell more products to more markets. Indeed, on aggregate, a 10% increase in ‘bilateral digital connectivity’ raises goods trade by nearly 2% and trade in services by over 3%. Digitalisation is important for all sectors, including agriculture, natural resources and textiles, but it is most important for exports in more sophisticated manufactures and digitally deliverable services. Digitalisation is also associated with countries drawing greater benefits from regional trade agreements (RTAs). When combined with an RTA, a 10% increase in digital connectivity gives rise to an additional 2.3% growth in goods exports (Lopez-Gonzalez and Ferencz, 2018[3]). The benefits of digital trade were already apparent before the COVID-19 pandemic, but the current crisis has further accelerated the shift towards a digital economy and underscored the need for governments to enable digital trade as a means to mitigate the economic slowdown and speed up recovery (OECD, 2020)[9].

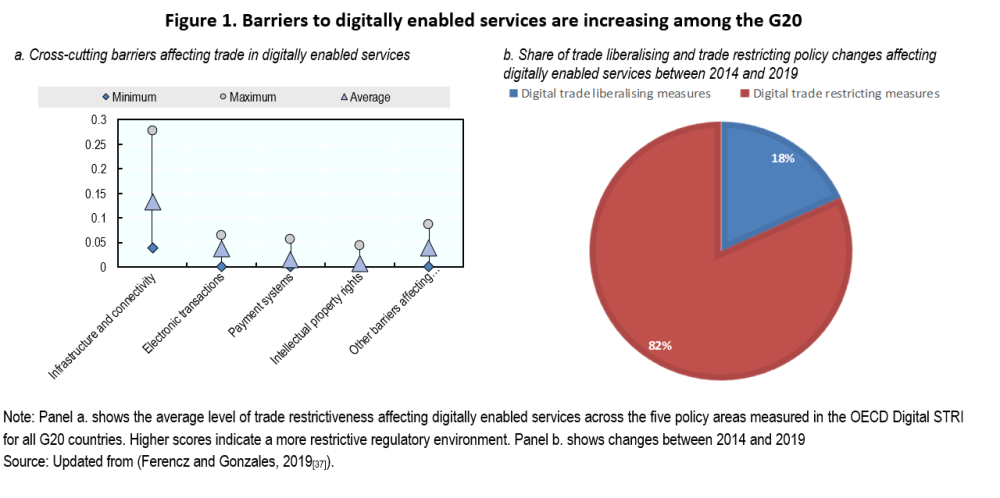

However, the benefits of digitalisation for trade are not automatic and can be compromised by restrictive trade policies. Barriers affecting services related to communications infrastructure and connectivity, including data connectivity, are particularly cumbersome as they affect all trade supplied through digital networks (Figure 1a).[1] Since 2014, the landscape for digitally enabled services has become more restrictive (Figure 1b). This involves, in particular, measures affecting communications infrastructure and connectivity, among which are measures affecting the cross-border movement of data. In addition, trade restrictive measures affecting electronic means of payments and online payment services have also grown, along with increased localisation requirements for foreign digital services providers (e.g., through a local agent or representative). Taken together, these measures can reduce firms’ ability to access world-class digital services at competitive prices.

How measures affect trade is also changing. A simple digital trade transaction rests on a series of enabling or supporting factors. For instance, ordering an e-book depends on access to a retailer’s website. This in turn depends on the regulatory environment setting the conditions under which the retailer establishes the webpage and the cost for the consumer of Internet access – a cost which, in turn, is affected by the regulatory environment in the telecommunications sector. The purchase of the e-book will also be affected by the ability to pay electronically, the download capacity (bandwidth) of the network and the tariff and non-tariff barriers faced by the physical device used to read the e-book (the e-reader). A barrier on one of these transactions will affect the need or ability to undertake the other transaction. Barriers traditionally associated with goods trade, such as tariffs, may have important implications for services delivery (and viceversa).

This means that market openness in the digital age needs to be approached more holistically, taking into consideration the full range of measures that affect any particular transaction. At the same time, making the most out of digitalisation for trade requires thinking more carefully about how trade policy interacts with related policy domains such as innovation, infrastructure, competition, taxation, consumer protection, skills and data governance.

One of the most important issues for digital trade is the cross-border movement of data. Today, trade and production are heavily dependent on moving, storing and using digital information (data), increasingly across borders. Data enables the co-ordination of international production processes through GVCs, helps small firms reach global markets, can be an asset that can be traded, or a conduit for delivering services, and is a key component for automation in trade facilitation. It is increasingly difficult for an international trade transaction to take place without a cross-border data transfer of some sort.

However, the pervasive exchange of data, including across borders, has fuelled concerns about the use and, especially the misuse, of data, amplifying concerns about privacy protection, digital security, intellectual property protection, regulatory reach, competition policy and industrial policy. As a result, countries have been adopting and adapting regulations addressing the movement of data, often introducing new measures that condition the movement of data across borders or, in some cases, measures that mandate that data is stored or processed in specific locations (data localisation). The resulting patchwork of rules and regulations is making it difficult not only to effectively enforce public policy goals such as privacy and data protection across different jurisdictions, but also for firms to operate across markets, affecting their ability to internationalise and benefit from operating on a global scale. The internet is global and borderless but regulations are not.

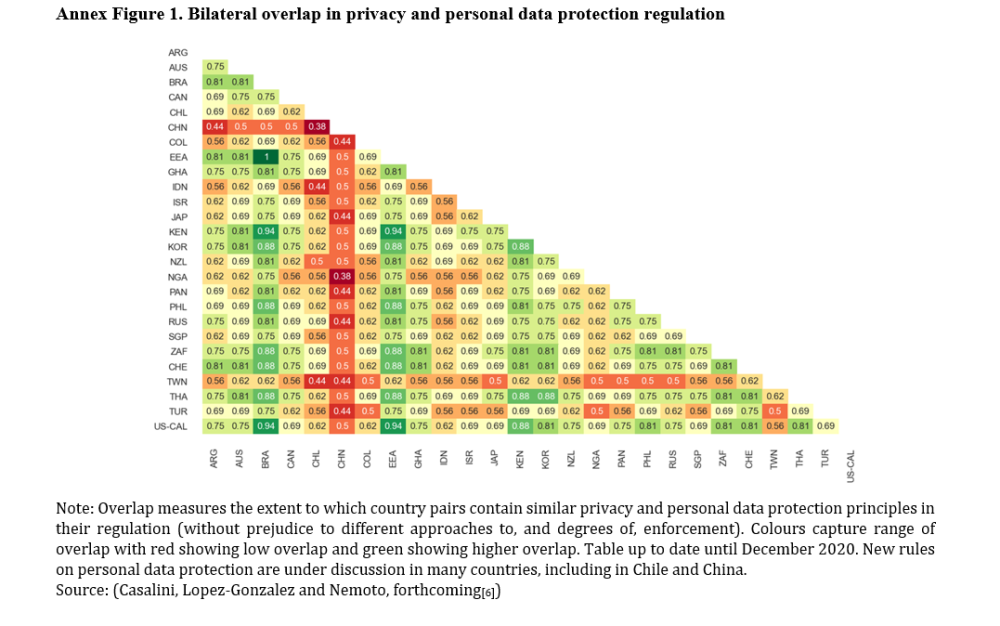

Governments have been using a range of instruments to ensure that, upon crossing a border, data is granted the desired degree of protection or oversight. However, there is no one, single, mechanism to enable what has come to be called ‘data free flows with trust’. Governments pursue different, or even multiple and complementary, approaches (Casalini, Lopez-Gonzalez and Nemoto, forthcoming[5]).

Despite wide differences across instruments, a range of commonalities emerge within and between instruments. For instance, whether through unilateral mechanisms, trade agreements or plurilateral arrangements, there appears to be consensus on the dual goals of safeguarding data and enabling its flow across borders. There is also growing evidence of convergence, whether in the trade agreements which combine binding data flow provisions with provisions on privacy and consumer protection frameworks, or in the principles that underpin domestic privacy and personal data protection frameworks. Finally, there exists a high degree of complementarity between instruments. Unilateral mechanisms draw from, and contribute to, plurilateral arrangements and trade agreements increasingly reference plurilateral data protection arrangements along with their binding data flow provisions. Together, these can be seen as indicating the emergence of an international architecture, or architectures, aimed at reaping the benefits of data flows while enabling governments to meet other legitimate public policy objectives.

Digital trade, and the rules that underpin digital trade transactions, raise new and complex issues, often at the intersection of different policy communities. Understanding what and how barriers affect digital trade and better measuring digital trade will remain important priorities for all, as will be finding ways to engage in dialogue across different policy silos. Where EU-US cooperation is concerned, there are a number areas where the EU and the US can build on their shared objectives in the context of discussions in the WTO’s Joint Statement Initiative on e-commerce. Low hanging fruit in the areas of facilitating electronic transactions via the promotion of wider adoption of UNCITRAL instruments could help deliver quick benefits to both EU and US firms. But there might also be scope for the EU and the US to lead the way in identifying how to digitise trade processes more broadly (most trade remains paper based), including through the use of e-transferable records via the adoption of UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Transferable records (which has only been ratified by Singapore and Bahrain). This would deliver an important boosts to transatlantic and global trade.[1]

On data flows, a solution is more challenging. At the bilateral level, Privacy Shield, or its predecessor, Safe Harbour, provided a short-term ‘fix’ to transatlantic data flows, but longer term solutions are needed, including in the context of providing a counterweight to emerging approaches (e.g. China and India). There are many factors that drive the EU and the US appart. Fundamental differences in the legal systems as well as cultural differences which underpin different approaches to privacy and data protection. The issue of ‘who gets to decide?’ also matters. In the EU, GDPR is the remit of DG Justice, and when discussions took place between the EU and the US on Privacy Shield after the Schrems II case it was the Commissioner for DG Justice, Didier Reynders, which negotiated with the Commerce Secretary, Wilbur Ross. Discussing across policy silos is difficult.

Despite these important differences, there are signs that the EU and the US do not disagree on the end goal of enabling data flows with ‘trust’, but rather on the means to attain this goal (Casalini, Lopez-Gonzalez and Nemoto, forthcoming)[6]. In terms of unilateral approaches, for the US enabling data flows with ‘trust’ is achieved by empowering the private sector to provide different degrees of protection, but with liability for data misuse (ex-post accountability). For the EU, enabling data flows with ‘trust’ is sought through finding common ground on regulatory approaches and enforcement mechanisms related to data protection (public adequacy). In terms of other instruments, the EU seeks greater convergence on the principles that underscore privacy and data protection as a pre-requisite of trust and therefore a pre-condition for transfer (Convention 108). However, for the US (and others), trade agreements can be seen as a means for seeking consensus on unrestricted transfers in the context of exceptions for meeting legitimate public policy objectives (provisions often reference plurilateral arrangements in the area of privacy and data protection).

A greater recognition and understanding of each others approaches and more emphasis on commonalities rather than differences, and how these relate to emerging approaches, could provide the grounds for agreement on the issue of data flows in the future. Although much still needs to be done, there are some promising signs. There are growing discussions in the US about the possibility of adopting new federal rules on privacy and personal data protection. At the same time, the EU has increasingly been ‘experimenting’ with approaches to cross-border data flows in trade agreements, most recently in the EU-UK TCA. Building on these, the EU and the US can try to enable a greater degree of interoperability or convergence in data governance with a view to enabling more trade, bilaterally and globally. Progress in the area of data flows between the EU and the US will be an important step towards more interoperable and better global data governance

[1] Barriers to digital trade are identified using the OECD Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (DSTRI) which was developed for all G20 countries in 2019 under the Presidency of Japan (see (Ferencz and Gonzales, 2019[37])). It covers regulatory data for 2014-2019, and it is updated annually. For more details, see: https://sim.oecd.org/Default.ashx?lang=En&ds=DGSTRI

[1] In other areas which are likely to remain contentious, such as consumer protection, cybersecurity, non-discrimination and limited liability. The EU and the US could start promoting further and more targeted transatlantic multistakeholder dialogue involving different policy communities, civil society and private firms to better understand the issues at stake.

Casalini, F., J. Lopez-Gonzalez and T. Nemoto (forthcoming), “Mapping commonalities in approaches to cross-border data transfers”, OECD Trade Policy Papers.

[6]

Ferencz, J. and F. Gonzales (2019), “Barriers to trade in digitally enabled services in the G20”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 232, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/264c4c02-en.

[5]

Lopez-Gonzalez, J. and J. Ferencz (2018), Digital Trade and Market Openness, https://doi.org/10.1787/1bd89c9a-en.

[3]

Lopez-Gonzalez, J. and M. Jouanjean (2017), Digital Trade: Developing a Framework for Analysis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/524c8c83-en.

[1]

OECD (2020), Leveraging digital trade to fight the consequences of COVID-19, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/leveraging-digital-trade-to-fight-the-consequences-of-covid-19-f712f404/.

[4]

WTO (2018), World Trade Report 2018: The future of world trade: How digital technologies are transforming global commerce, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/world_trade_report18_e.pdf.

[2]

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more