Denise Moreno Ducheny, Formerly UC San Diego

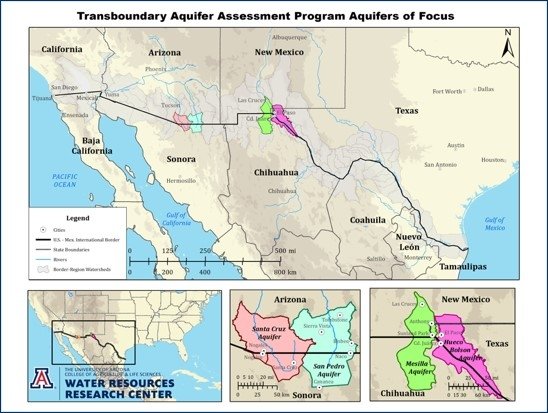

The heart of the frequent conflict in the Texas region is the fundamentally flawed premise of the 1944 Treaty – the notion that water is “owed” by one country and watershed to the other - presuming to “trade” a specified quantity of Colorado River water to Baja California in exchange for Rio Bravo/Grande River water to Texas. As such, the Border Region needs to adopt watershed management strategies which have evolved over the last 20-30 years in various regions, including within California. Watershed management plans for each specific watershed will be required to address climate change, drought conditions, efficient agricultural water use, and other environmental issues to develop long-term sustainable use strategies and projects. This principle of watershed management applies equally to groundwater basins. For many years, we have lacked baseline studies of binational groundwater basins, which are mandatory to effectuate any long-term strategies. One key component of creating sustainable groundwater basins will be employment of aggressive water re-use and utilizing groundwater basins for storage. This is an issue that will require revision of the legal framework in all jurisdictions. California recently implemented some groundwater monitoring and regulation which may serve as a starting point for others.

Carlos Rubinstein, RSAH20

Simply, live within the actual amounts of water that are available and committed as per the treaty. Do not continue to plant and expand acres for water-intensive perennial crops that exceed by demand the water that is actually available. And Mexico must set aside water for treaty compliance before making allocations to the internal irrigation districts (the United States does this on the Colorado).

Sharon Megdal, University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center

With the obvious pressures on and competition for water resources, it is important for the players in the region to work together to identify options for addressing imbalances in supply and demand and identify pathways to solutions. We all know the work is difficult and without a definite endpoint. Of course, it is made more difficult by different languages, cultures, economic conditions, and government budget priorities. It is important to get the stakeholders on the same page regarding the situation and then look to the implications of alternative solution sets.

Sergio Alcocer, UNAM

The problem at the Rio Bravo watershed is both chronic and systemic. More water than available has been allocated on the Mexican side. Therefore, the expected amount of water to be released to the United States is typically short, unless extraordinary rains occur. A serious, unbiased, technical study should be conducted for the watershed. This should include, among others, modeling of all inputs and outputs of the watershed on both sides of the border. Based on a resilience modeling approach, different scenarios involving policy decisions and technical modifications should be jointly developed, potentially by Mexican and U.S. universities with expertise on the subject. In such modeling, climate change, economic and population growth, dam expansion, and water efficiency improvements, should be also studied. The North American Development Bank (NadBank) could be a key player for granting the money for a multi-year project to address these issues.

Erik Lee, North American Research Partnership

First things first: the two governments need to fully acknowledge the reality of climate change and its impacts in order to come up with joint approaches to dealing with the water changes for the strategic U.S.-Mexico border region. In the United States, the Trump Administration is withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement on the day after the election, but the same federal government has issued the National Climate Assessment, which spells out very clearly that temperatures are rising and water supplies are shrinking in the Southwest. I think it is clearly the case that the federal governments know what the situation is and what needs to be done to mitigate and adapt.

Overall, I see a greater role for locally-driven innovations in terms of management and technological implementation. Water districts and utilities in the United States are powerful actors and are very cognizant of their role in addressing water resource pressures. This part of the world is facing existential challenges from climate change and water scarcity that are simply not felt in Washington. On the other hand, however, water issues are front and center in Mexico City, so perhaps there may be greater political will in Mexico to address these issues. Technological fixes which may once have seemed too futuristic, unfeasible, and expensive may all of a sudden look viable and even necessary. Solar desalination, exploiting brackish waters, large-scale methods of condensing water from water vapor, and greater use of protected agriculture may all see broader implementation.

While Mexico’s commitment to sustainability has clearly dropped with the López Obrador Administration, one area in which Mexico is quite advanced is in protected agriculture (greenhouses), which uses water more efficiently and productively than open-field agriculture. States such as Baja California and Sinaloa have seen tremendous growth in the use of protected agriculture. Could Mexico’s federal government encourage more of this throughout the North? Could we see a wave of technology transfer from Mexican agriculture to U.S. agriculture?

Mario López Pérez, Permanent Forum of Binational Waters

This is an enormous opportunity to amend the path towards the indivisible binomial of water sustainability in the basin and compliance with the 1944 Treaty. The strategy must focus on short, medium, and long-term results. This cannot be thought of as being resolved in five years, but instead having partial results in that time. The strategy must contain at least these five elements for the Mexican side:

- Improve the management of water resources, including:

- State-of-the-art monitoring technology of the watershed's hydrological cycle (demand and supply).

-

Separate the operation of the hydraulic system to Ojinaga and from there to downstream; think about a policy of maintaining an optimal minimum level in international dams for contingencies due to drought.

-

Integrate the environmental flow to help ensure the hydrological continuity of the system, the supply of water for domestic use, and promote the recharge of aquifers (using Solutions Based on Nature - SBN).

-

Conclude the development of water allocation rules and sign them in a Concertation and Coordination Agreement within the Basin Council; test and modify them annually, if necessary, and eventually convert them to a Regulation in accordance with LAN - reduction of water use - given the legal and administrative difficulty in modifying a Regulation annually.

-

Incorporate technologies of high water efficiency in irrigation and production chains from the farm to the agro-industry; resize the Irrigation Districts in parallel to this technological modernization.

-

Create new water sources (Act 319 of the Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas - CILA):

-

Brackish and marine water desalination for the northern populations of Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, and Coahuila.

-

Conduction of water from humid areas (Tamaulipas) for irrigation in the north of Tamaulipas.

-

Implement environmental flows.

-

Build aquifer recharge works / create water banks; think about building underground dams (decreased evaporation).

-

Build the third international dam on the main channel.

-

Update and implement the territorial zoning plans of the basin states to restore the ecosystem balances necessary for a healthy hydrological cycle (SBN) and decree protection of recharge zones.

This cannot be done in five years, but a permanent and long-standing process can be agreed upon. For the U.S. side, similar elements need to be envisioned, discussed, and agreed upon.

Gabriel Eckstein, Texas A&M University

The Minutes system of the 1944 Treaty serves as almost a separate regime because it enables the development of legal and practical mechanisms that are easier to implement since there’s no requirement for congressional approval. The Minutes are actually interpretations or clarifications of the treaty, not amendments to it. This system offers opportunities for innovative and flexible solutions to adapt to changes and address situations such as: growing populations, increased economic development, water quantity changes, climate change, etc.

For Mexico, however, their top-down implementation regime creates challenges, and this is an area where Mexico will continue to face significant problems until changes are made. Until the Mexican government takes into account local and stakeholder involvement and moves away from a command-and-control and centralized approach, the existing challenges will persist.

What’s currently transpiring on the Rio Conchos is calling for the type of creativity that was achieved on the Colorado River. From the upper basin of the Rio Conchos down to where it meets the Rio Grande, natural losses are pretty significant. Why couldn’t Mexico deliver the water it has stored in the Falcon and Amistad reservoirs through a transfer of rights in order to pay on its water debt? The water is there in the two reservoirs, so why do they have to deliver the water solely from Rio Conchos?

*Gabriel Eckstein’s responses are paraphrased, based on an interview done with him on October 16, 2020.