Although the exact definition of the blue economy is still being developed, there seems to be strong consensus that it relates to the ocean, or to water more broadly, and that it must be sustainable. Just as green business is the subset of all business, the blue economy is the subset of the ocean economy that is leading with solutions that are sustainable, have an ocean-positive benefit, and will be part of a global circular economy. While this is self-evident as a goal, how can investors get there? What are those of us leading this effort doing? In what should one invest? And, how will investors know if they are succeeding? Allow me to briefly answer these questions to help investment advisors and asset owners (e.g., high net worth individuals, investment banks, pension funds, or sovereign wealth funds) play a role in creating the best outcomes for the ocean, and for those people who depend upon her.

How should investors enable a sustainable blue economy?

To enable a blue economy approach to support ocean protection, and argue in favor of restoration of coastal and ocean ecosystems, we must be convincing and clear about the value generated by healthy ocean and coastal ecosystems for food security, storm resilience, tourism recreation, etc. While coastal communities and small island nations are all too aware of their “gifts from the sea,” global markets generally externalize the true costs of activities that harm the ocean. The Ocean Foundation’s goal is that those costs will be internalized to governments and businesses—and that the profits and benefits go to those who steer a path towards minimizing and mitigating harmful activities while capitalizing on positive activities.

So, part of our work is to promote consensus on how to quantify what often are called non-market values: provisioning (such as food for subsistence fishers), regulating (storm surge and waves), supporting (pollution filtration and oxygen production), and cultural (aesthetics, recreation, fun, and inspiration). And at the same time, TOF works to ensure that those non-market values are not just quantified, but also protected and even enhanced. For example, adding both a blue economy and an ocean-climate value to ask if current regulations protect seagrass meadows, mangroves, and salt marsh estuaries that are critical carbon sinks and mitigate the greenhouse gas emissions and other effects of human activities, while replenishing ocean life.

On the flip side, there is the issue of establishing the risk to human activities (and costs) if we fail to adopt “bluer” economic activities or incentivize reducing negative activities by ensuring that companies and governments internalize those costs. Thus, TOF will continue to identify and quantify the cumulative effects of negative human activities, such as air pollution, land-based sources of marine pollution, including plastic loading; and extraction of resources from fish to fossil fuels. These and other activities are a threat to the marine environment themselves, but also to any coastal and ocean generated value to the global economy at every level.

Ocean generated value is threatened by cumulating human activities

- CO2 emissions (acidification)

- Over-fishing/by-catch

- Decimation of top predators

- Open pen fish farming

- Noise pollution from shipping, etc.

- Minerals and petroleum extraction

- Coastal wetlands, mangroves, and seagrass destruction

- Tropical reef and deep, cold water coral destruction

- Deliberate and accidental toxic dumping

- Toxic run-off from roads, farms, and other human settlements (algal blooms – hypoxia)

- Plastic loading

With a firm understanding of the values generated or at risk, investors have begun to design the blue finance mechanisms to pay for conservation and restoration of coastal and ocean ecosystems. This can include philanthropy and multilateral donor support via design and preparation funds; technical assistance funds; guarantees and risk insurance; and concessional finance. There is also likely a part to play for private and public investment capital. Such finance instruments must respect cultural heritage, limit risk to vulnerable communities and nations, and ensure that benefits accrue at the source. For example, new emerging values, such as those related to biotechnology, will require both legal oversight and start-up financing to ensure their development is equitable and ocean-positive. More can be done.

What are we doing?

On the public equity side, The Ocean Foundation (TOF) and I are the exclusive expert ocean and climate advisor and research collaborator to Rockefeller Capital Management. As such, we provide due diligence and scientific validation on how companies may affect the coasts and ocean, to enhance idea generation, research, and engagement process. TOF and our investment partners engage the private sector so that business activities are collaborative and regenerative, enable environmental and climate resilience, integrate into local economies, and generate economic benefits and social inclusion of communities and Indigenous Peoples. This covers two ocean-centric portfolios:

- The "Rockefeller Climate Solutions Fund” launched 2012 was the first ever ocean-centric climate solutions fund (with $220m AUM it is now a mutual fund in the USA, UCITS in Europe), evolving from its origins as the Rockefeller Ocean Strategy. Through this unique, globally diversified impact investing opportunity for the ocean-climate nexus with all-cap, private placement in active, long-only global publicly traded securities, we have created a triple-screened fund.

- In collaboration with Credit Suisse (CS) and Rockefeller Asset Management (RAM), The Ocean Foundation launched the Rockefeller Credit Suisse Ocean Engagement Fund (September 2020, $780m AUM) to meet the increasing demand from institutional and private investors to invest in the Blue Economy. This thematic equity strategy focuses on the UN Sustainable Development Goal 14, and employs constructive engagement with portfolio companies to generate alpha and positive ocean health outcomes. We advise and steer portfolio companies away from ocean-harming practices, through dialogue with their management teams. For this fund, I participate in engagement calls or meetings with portfolio companies around the world, push such companies toward operating in more ocean and dependent community friendly ways (and on the development of metrics with Rockefeller for measuring such change). Regarding coastal and ocean ecosystems this engagement to change corporate products or behavior can include work to reduce plastic pollution, land-based sources of marine pollution, fishing practices etc. It can also include sustainable travel and tourism practices (for which I also have a depth of experience).

And, in parallel with these two public equity funds, TOF, Rockefeller, and Credit Suisse are developing a private equity portfolio and a fixed income strategy that will complement and work in parallel.

In what should one invest?

Let us propose seven major categories of sustainable blue economy investments, which are at varying stages and can accommodate public or private investment, debt financing, philanthropy, and other sources of funds.

- Coastal Economic & Social Resilience. This can include restoration of coastal “blue carbon” sinks (sea grass, mangroves, and coastal marshes), and making coastal infrastructure (utilities, roads, etc.) more resilient. It also includes working to ensure our communications systems, seafloor telecommunications cables, utilities, and solid waste management facilities are storm ready, including re-design for inundation and buffering with restored mangroves or marshes. Resilience means updating risk and insurance products in ways that reduce incentives to build or design without consideration of risk. This also means making sure coastal and marine tourism is both built and operated to be sustainable and not causing more harm. We’ve tried to help communities meet the need for ocean acidification monitoring and mitigation projects—through both policy and science—especially where shellfish production is a key part of the coastal economy or subsistence diets. This includes taking on significant blue carbon conservation and restoration projects. All these investments represent diverse industries or emerging industries, and diverse supply chains, generating economic activity as well as sustaining existing economies by making them less vulnerable. Many of these coastal resilience projects are public interest projects, may meet the definition of “climate actions” and thus are more likely to be financed via government-issued bonds.

- Improving Ocean Transport. Shipping is ocean-positive in the sense that moving a ton of product by water has the lowest carbon footprint—which is not to say no carbon footprint. The ocean transport sector is under significant pressure to reduce emissions and to increase the sustainability of their operations (including ocean noise, waste streams, and energy efficiency)—from portside to high seas. The blue economy lens for shipping offers many kinds of investment opportunities: New engineering solutions to develop zero-emission vessels; Fuel substitution (electric, di-methyl ether, green hydrogen, ammonia); Alternative fuel propulsion systems (computer aided sails, for example); and new more efficient hull coatings and navigation systems. Ship builders can reduce chronic ocean noise with quiet ship technology. And, governments can make sure all ports are more sustainable in their energy use, cargo management operations, and waste management.

At TOF, we have done substantial research synthesizing the many ways investors can help make the maritime industry more sustainable.[1] This sector is great for selective investment in those companies leading with solutions, or in companies whose alfa can be improved by changing their products or practices. For example, via the Ocean Engagement Fund, we have been engaging with major shipping firms to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions via new propulsion systems or fuels, as well as improving their shipbreaking (end of life ship recycling) practices.

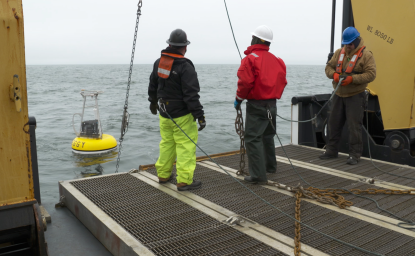

- Ocean Renewable Energy (such as power generated by waves, tides, currents, OTEC, and wind). This kind of investment can include both expanded R&D and increased production. And, investors can explore integrated ocean management to balance needs of other ocean users, as well as the potential effects of increased ocean noise and other operations on sea life and coastal and island communities. The monitoring equipment itself represents an investment opportunity. Investment in this sector can be both private and public equity in energy firms, fixed income instruments for public utilities, and in some cases, government bonds for extremely large projects.

- There are real and urgent Ocean-Sourced Food investment opportunities: Sustainable aquaculture, as well as coastal and oceanic fisheries. These sectors have significant embedded equity and related issues that can be addressed by appropriate investment with a true blue economy lens. In these sectors, investors can explore opportunities for returns from emissions reductions from fisheries operations, including aquaculture, wild capture, and processing (e.g., low-carbon or zero-emission vessels), energy efficiency in postharvest production (e.g., cold storage and ice production), and alternative aquaculture feeds (algae, microbial, fungal, insect). Investors can also analyze new emerging sub-sectors including new cellular manufactured seafood (such as BlueNalu), kelp farming, as well as fisheries byproduct transformation. Meanwhile NGOs and others who are concerned about ocean health can seek related regulatory changes that eliminate fuel subsidies for fishing fleets, and call for vessel and gear improvements that increase efficiency, while strongly constraining catch to sustainable levels. Again, this sector is great for selective investment in those companies leading with solutions or with tools to increase monitoring and enforcement, or in companies whose alfa can be improved by changing their products or practices. At TOF we have engaged with retailers and fishers and intermediaries to improve sustainability through transparent, credible traceability of sources among other improved practices.

- Fifth, investors can explore financing Ocean Biotechnology -- the innovative marine molecules sector that uses living systems and organisms from the marine environment to develop or make products, which can include: nutraceuticals (dietary supplements and food additives that provide a medicinal benefit, or improve well-being); and cosmetics (marine biotechnology raw materials for cosmetics, holds huge potential for sustainability). Right now, this will be private equity in companies at the pre-competitive (seed or “angel” funding) level, early stage risk investment (venture capital) level, or late stage private equity (where going public is the likely exit strategy). In addition, there may be opportunities for investing in joint-ventures or corporate facilitations—especially when engaging the community to ensure that biological and cultural heritage are not only respected but monetized to the extent that ensures that communities are not losing livelihood while profits are generated elsewhere.

- Sixth, there is a tremendous demand for investing in Cleaning Up the Ocean. Humankind needs to work quickly to transition away from offshore oil and gas, and clean up its legacy infrastructure. All communities must pursue pollution reduction in coastal waters to remove contaminants and excess nutrients to restore ecosystem function. Island and coastal communities are facing unusual dead seaweed events in tourism areas, as well as other nutrient-fueled harmful algae blooms (smelly, unsightly, and costly to clean up). With climate change kindled storm surge, investment is needed in removing and disposing of post-storm debris, as well as in storm-resistant sewage management systems (for example). It is great to see rising investment in cleanup of marine debris, especially plastic pollution in our waterways and ocean. Addressing marine debris must include thoughtful island nation waste management solutions and increased awareness of the potential harm from ship groundings, and other at-sea accidents to improve container management. Plastics management is top of mind for many consumers as well as investors. We envision investments in recycling and upcycling technologies, preventive management, microalgae that can eat plastic, as well as redesigning plastic to develop next generation materials that have potential to be part of the circular economy / sustainable blue economy. Plastic must become safe, standardized, and simplified to be managed. Like biotech, a lot of these investments are private equity opportunities, but there are also many public equity companies making a play in the space. And, this sector is especially opportunistic for selective investment in those companies leading with solutions, or in companies whose alfa can be improved by changing their products or practices. Hence, TOF and our investment partners are engaging consumer goods / brands on eliminating unnecessary/problematic plastic packaging; transitioning to reusable packaging; ensure all packaging is reusable, recyclable, or compostable; and incorporate or increase recycled content in plastic packaging. Alongside this, we ask all companies about their plastic footprint, recycling practices, as well as environmental justice aspects of plastic production, consumption, and improper disposal.

- Finally, investors must anticipate Next Generation Ocean Activities. At TOF we predict this will include investing in infrastructure-based adaptation to relocate and diversify economic activities; sensors and other equipment to monitor unseen harm from rising sea levels and saltwater intrusion, and when and how to relocate people and infrastructure. Investing to expand nature-based solutions for carbon capture and storage technologies, and improving our ability to map and identify the best places to initiate restoration/planting where water levels change. Pursuing research and development of other nature-based solutions that take up and store carbon (micro and macro algae, kelp, and the biological carbon pump of all ocean wildlife). We also believe that many of the ocean-based activities outlined above will need redesigning with new technologies to adapt to changing conditions, minimize harm to sea life and human communities, and achieve an ocean-positive goal in operations. And there will be some investment needed to exercise care that geoengineering technology solutions are examined carefully for their efficacy, economic viability, and potential for unintended consequences.

How will investors know if we are succeeding?

Meaningful blue economy investing must have real, measurable positive outcomes. Financial institutions, such as banks, insurers, and investors, are critical to the long-term health of our global ocean, however they are often poorly informed about (i) the impact of their investments on the ocean economy and (ii) their portfolio exposure to financial risks from the decline in marine ecosystem health. In some cases, it’s understandable: It's hard to build in the air we breathe as a cost or a risk—but it is the outcome if we don’t improve the human relationship with the ocean. In other cases, it’s just a question of adjusting the lens. Something that takes time, but is achievable.

I sit on the UNEP Guidance Working Group for its Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Initiative, which has developed “Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles.”[2] These 14 principles, constitute a broad framework for investing in the blue economy. They are useful and are intended to get investors to state up front that they care about the health of the ocean, not just a return on their investments. However, the Principles are not designed to measure results of such investing.

Similarly, the Blue Natural Capital Positive Impacts Frameworks[3] identifies opportunities, and looks at how to assess potential investments. It has developed a Blue Natural Capital Positive Impacts Framework to guide the monitoring of projects and measure positive impacts. However, it is narrower than the entire blue economy as it is focused on key performance indicators relating to the positive effects on ecosystems and species directly, i.e., the natural capital found in coastal and marine environments which provide ecosystem services.

If all those in favor of ocean health and abundance are seeking to establish a global standard for measuring a portfolio’s exposure to sources of “blue” revenue, such as fishing, shipping, offshore wind, maritime and coastal tourism, and marine biotechnology then I would humbly suggest a 3 tier approach:

The first tier is perhaps obvious, but sadly sometimes things can go imperfectly as the result of fraud, mismanagement, or irreproachably fail as the result of uncontrollable events. Thus, investor self-evaluation starts with asking whether the investment was consummated, and, whether it made an ocean business better / more sustainable through a change of product, practice, or service? For example, if one is investing in better fishing gear, were funds invested or spent as directed, and in a timely manner. And, if so, did it make the company fish in what is expected to be a more sustainable fashion?

The second tier asks if such better fishing gear, and thus theoretically more sustainable practice provide for a positive ocean return? For the fishery, in the short term, this might be evidenced by less by-catch, less target species wasted, more focus on the right age or size of fish. For the longer term, did the new gear and practices result in greater biomass abundance within the fishery, and or for related or adjacent species? For the ocean more generally (and depending on the investment), this efficacy measure would call out a measurable direct environmental condition improvement / carbon sequestration or other ocean positive outcome? In fact, given the unquestionable urgency of addressing human disruption of the climate, reducing or eliminating greenhouse gas emissions, or promoting carbon sequestration should be critically included elements of all investments going forward.

The third tier asks about economic and social sustainability. For without such sustainability the investor, the fishing company, and ocean-dependent communities will conclude that the effort was not worthwhile and it will fade away. So, in this last tier, the investor will unsurprisingly ask herself if she received a positive economic return on her investment. And, was that return as good or better than any other investment that might have been made. When the investor is a government pursuing the public good, such an economic return can also include a reduction in exposure to financial risks from the decline in marine ecosystem health. And the conscientious investor will seek to keep social sustainability co-equal with whether the investment created outsized returns when compared to key benchmarks. This means asking whether any nearby ocean-dependent communities benefit from an improved economic resilience / food security / human health etc.? This can be indirect, through the transition to more sustainable livelihood projects that will support the development of profitable activities based upon the ecosystem services provided by healthy coastal and ocean ecosystems like ecotourism, commercial fishing, and beekeeping in the medium- and long-term. This must include asking if disparities in diversity and equitable opportunities and practices are addressed such that benefits are justly distributed. And, because all projects should highlight the necessity of local support for successful projects, an investor should deliberately engage members of traditionally marginalized groups in decision making.

These three tiers can be fleshed out further, and when doing so can draw upon best practices from other finance and investment sectors such as those looking at performance standards on environmental and social sustainability. As we do so, we need to keep in mind what measurable outputs investors can deliver themselves, versus the outcomes that depend on others to occur, we can often confirm these when another actor responds to our outputs (e.g., a report that leads to a legislature adopting a new policy) and/or something materially changes (e.g., more sea turtles are saved). And, we need to acknowledge our need to measure both.

Conclusion

Financing and investing activity is growing rapidly across asset classes and sectors that make up the blue economy. Many see it as a new source of economic growth, with new sub-industries and opportunities emerging to meet demand. In some ways, such activity is getting out ahead of definitions, benchmarks, and efficacy measurements. And, as we have seen too many times in the past, blindly chasing growth can risk a result with unintended consequences including reductions in, or loss of, natural capital, and deepening inequity in affected communities.

As the understandable effort to define the sustainable, equitable, and just blue economy continues to roll out, I have tried to explain how investment advisors and asset owners can support investment in the blue economy, including by engaging companies and pulling them toward better behavior, products, and services. After describing seven broad potential investment sectors, I have begun to articulate how to measure, evaluate, and learn from our investments in a way that gets beyond a simple “rate of return” metric of an investment over a specified time period. Thus, those of us working on investing in the blue economy must measure our direct outputs, and indirect outcomes that all build toward our goal of a healthy and abundant ocean.

The good news is that I believe the blue economy offers a major opportunity for the financial and investment sectors to deliver on climate commitments and other established Environmental, Social, and Governance investment objectives, whilst tapping into new blue sources of economic and social sustainability. The blue economy is not just about driving superior risk-adjusted returns; it also provides for the protection and restoration of more intangible blue resources such as traditional ways of life, carbon sequestration, and coastal resilience to help vulnerable states tackle the often devastating effects of climate change and biodiversity loss together.

[1] Mark J. Spalding, Angelica E. Braestrup, and Alexandra Refosco “Greening the Blue Economy: A Trans-disciplinary Analysis” for a book “Sustainability in Maritime Transportation: Towards Ocean Governance and Beyond” (Springer, 2021)

Author

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Empty Nets: Big Changes in a Great American Fishery

A Personal Account of Well-being and Salmon Systems