Mexico’s two million farms produce food and fiber for 130 million Mexicans and millions abroad, primarily Americans.

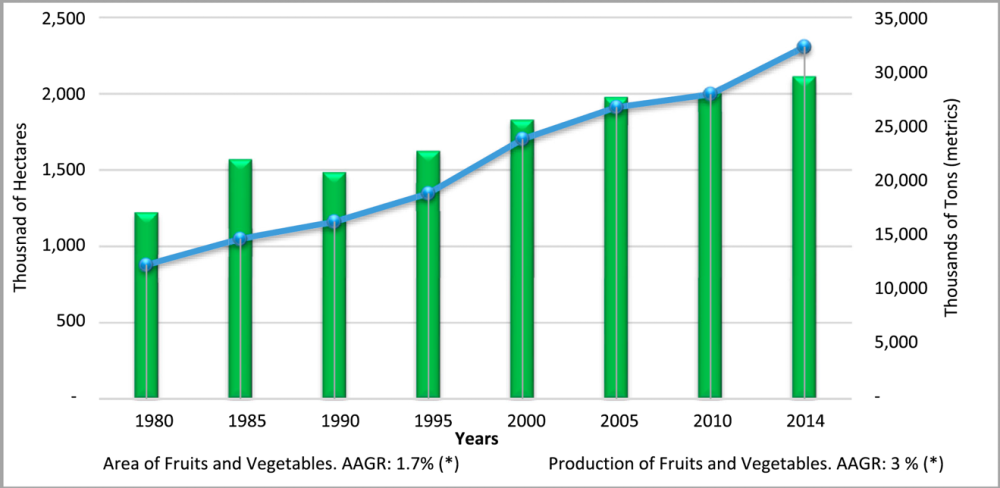

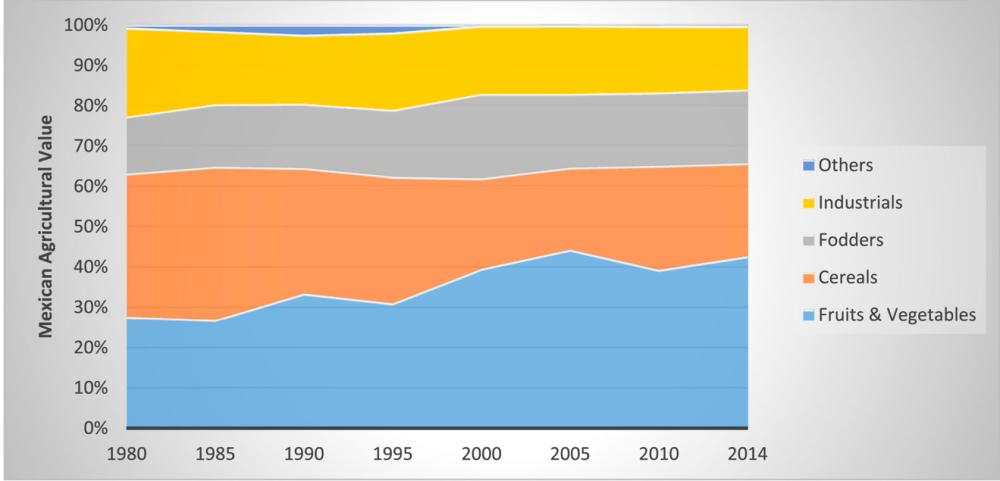

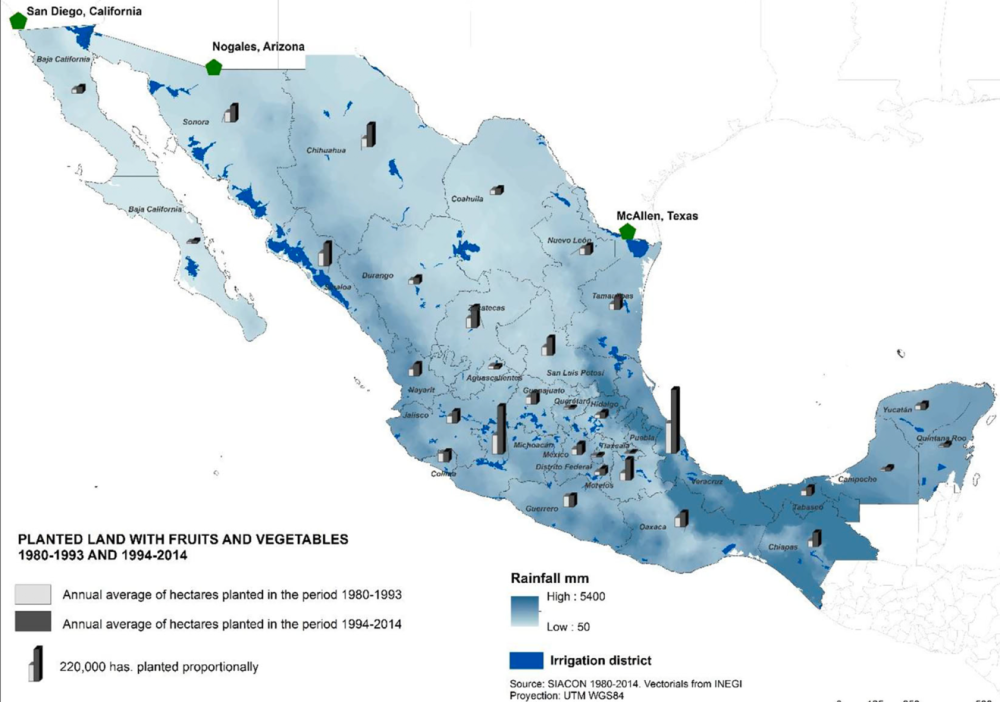

Mexico’s acreage of fruits and vegetables almost doubled from 1.2 million hectares in 1980 to 2.1 million hectares in 2014, and production rose even more as fruit and vegetable yields increased from 12 million tons to 28 million tons. Fruits and vegetables are more valuable than grains and other field crops, and their share of the value of Mexico’s agricultural output rose from less than 30 percent to over 40 percent between 1980 and 2014.

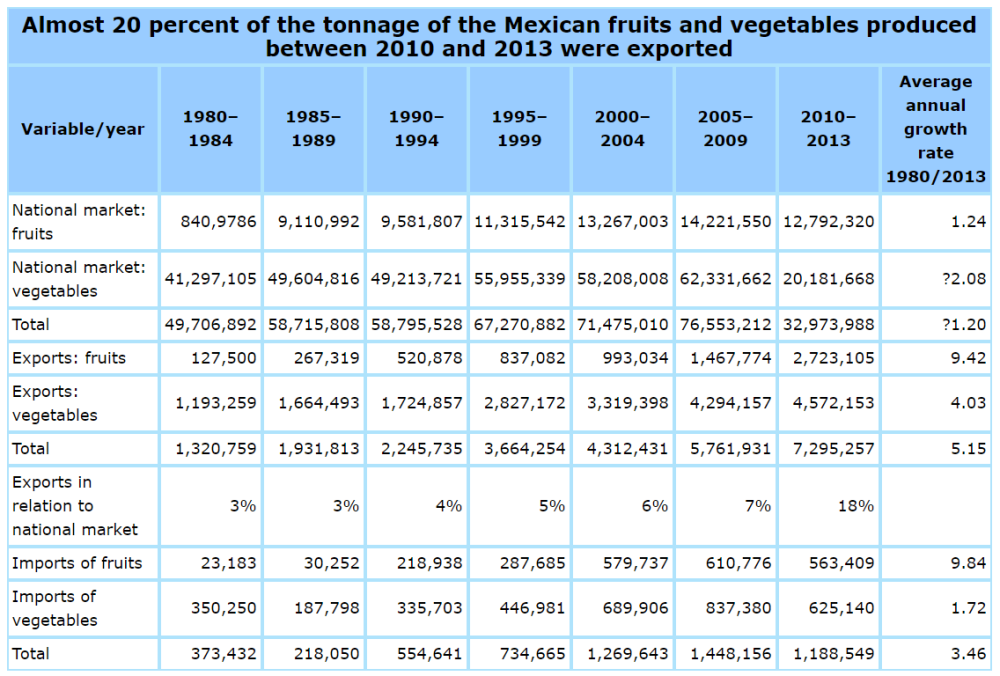

Most of the fruits and vegetables grown in Mexico are consumed in Mexico. For example, between 2010 and 2013, Mexico’s production of fruits averaged almost 13 million tons, with less than three million tons a year exported. Similarly, the production of vegetables averaged 20 million tons a year, including less than five million tons that were exported. Today, over 20 percent of the tonnage of fruits and vegetables grown in Mexico are exported.

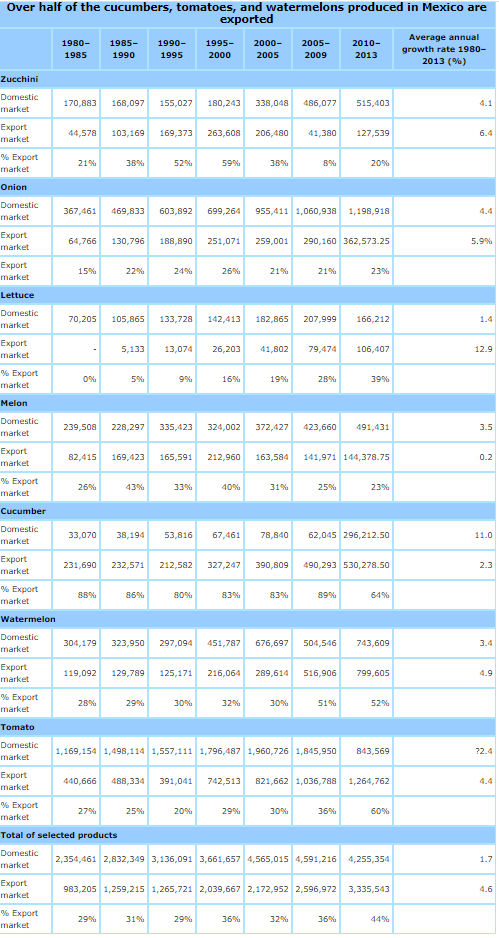

Export shares vary by commodity. Over half of the cucumbers, tomatoes, and watermelons produced in Mexico are exported.

Mexico’s major comparative advantage in producing fruits and vegetables for export is climate: Mexico can produce and export commodities to the US when there is very little competition from similar US produce (Florida tomatoes are an exception). Other Mexican advantages include lower wages and the availability of virgin land, which reduces pest pressures that build up over time. Critics of Mexican export agriculture emphasize that export farms often lease land for five to seven years, install irrigation and other infrastructure, and promise to leave these improvements if they stop farming the land.

Does the short time horizons of some exporters encourage a mining mentality, maximizing production for a few years and then moving on as water supplies are depleted and pest pressures mount? Critics of export agriculture say that the chemicals used to control pests are often mis-applied, endangering farm workers and nearby residents.

This raises an important question: are Mexico’s export farms footloose actors who enter an area, exploit its human and natural resources, and leave local communities to repair the environment and to care for ex-farm workers? If yes, governments could regulate or tax export agriculture to cover the cost of the externalities imposed on local populations and areas.

However, Mexico’s export agriculture is not footloose, since most export farms have been in the same area for decades, as with the 50-year old Sinaloa tomato export industry. There has been an expansion of export production, which helps to explain the quest for virgin land.

Instead of abandoned farms with poisoned land and sick ex-farm workers, many areas with export agriculture in Mexico are adding people and production. Farming can always be made safer for workers and more protective of the environment, but there is little evidence that export agriculture resembles the mining metaphor of extracting value and leaving toxic problems behind.

Mexican fruit and vegetable acreage almost doubled between 1987 and 2014, and tonnage more than doubled as yields rose

The share of fruits and vegetables in Mexican agricultural sales rose from less than 30 percent in 1980 to over 40 percent in 2014

Almost 20 percent of the tonnage of the Mexican fruits and vegetables produced between 2010 and 2013 were exported

The acreage of fruits and vegetables rose between 1980-93 and 1994-2014

Author

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Understanding Trade Promotion Authority (TPA): Implications for US Trade

The Innovative Landscape of African Sovereign Wealth Funds