I have delayed sending out my regular NAFTA update for a couple of weeks because things are changing so quickly that what seemed clear a month ago is up in the air today. On one hand, I still believe that no one ever made money betting on the swift conclusion of a trade agreement, but on the other hand, I think it’s fair to say that all parties are at least considering options that may result an agreement in principle, an agreement to agree? Such a decision would take place prior to achieving a substantive conclusion to many of the 32 negotiating chapters under consideration.

At the end of March, after seven rounds of negotiations (discussed in our March Canada Institute newsletter – link), the negotiating process moved to the political level. At that time, only six or so chapters were concluded, with little to no movement on the most contentious issues including the sunset clause, dispute settlement, government procurement, labor, and rules of origin in the automotive sector. No eighth round was scheduled but, throughout April, there were continuing meetings at the ministerial and working group levels. Mexican media now reports that ten chapters are now closed.

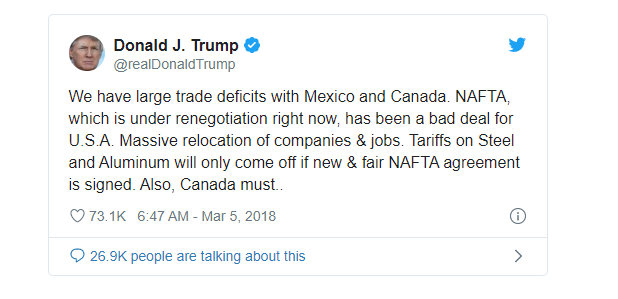

The spark for renewed political attention was President Trump’s tweet that a new NAFTA would be announced at the Summit of the Americas in Peru and the parallel assertion that steel and aluminum tariff exemptions for Mexico and Canada would be tied to reaching a NAFTA deal:

Factors in favor of prolonged negotiations:

- Canada has consistently said that it won’t accept a devalued NAFTA agreement. Accepting a deal before the contentious issues are worked out would limit Canada’s leverage.

- Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has campaigned on an economic nationalist platform fueled by anti-Trump sentiment in Mexico. If he becomes Mexico’s next president, will he accept an agreement that was championed by his domestic political rivals, especially one that seems to be rushed through by the Trump administration?

- The U.S. President is talking a hard line on trade but pressure from U.S. industry, the farm sector in particular, seems to have moderated his stance from ripping up the NAFTA to negotiating the deal to a conclusion. Republicans are wearing out the oval office carpet warning the President that bad trade policy could reverse the competitiveness gains generated by tax reform.

“But I keep hearing how we’re pushing NAFTA, we want it done. There’s no timeline. There’s no timeline. Now, in the meantime, nobody is moving into Mexico. Because as long as NAFTA is in flux, no company is going to spend a billion dollars to build an automobile plant. So I say this — I’ve told it to the Mexicans: We can negotiate forever. Because as long as we have this negotiation going, nobody is going to build billion-dollar plants in Mexico, which is what they’ve been doing a lot.

-President Donald J. Trump Remarks to Congress, April 12, 2018

Factors favoring an agreement in principle:

- Prolonged NAFTA negotiations and other trade volatility are chilling investment and production decisions in North America, hitting Mexico and Canada particularly hard. A quick deal might restore certainty.

- The U.S. trade bureaucracy has limited capacity to manage a multiple battles. With NAFTA less important than the China dispute, the U.S. may prefer to move North American trade out of the spotlight.

- The U.S. House of Representatives is predicted to shift to Democratic control in November. (A similar shift in the Senate is possible but less likely.) Democrats would not likely oppose a NAFTA deal – this is still the party that brought the U.S. into TPP negotiations – but the specific mandate given to USTR Robert Lighthizer is certain to change, putting more priority on labor and environment, for example, as well as domestic trade adjustment supports. Republicans may want to close the deal now to preclude that possibility.

Other Congressional questions

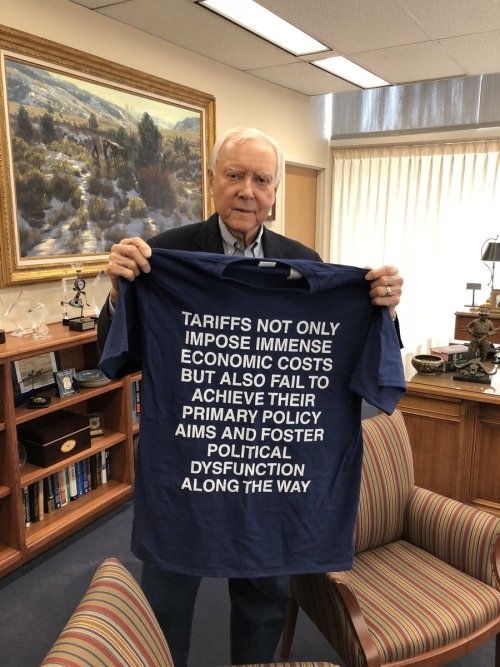

Several other Congressional issues are also affecting the negotiating dynamics. In late March, the President requested a three-year extension of Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) to cover completion of the NAFTA and other negotiations elsewhere in the world. Normally, TPA extension is a fairly routine matter but a number of influential legislators have expressed concern regarding Presidential over-reach on Congress’s delegated trade authority. These include freelancing on trade actions against China, invoking the rarely used national security exception, and hardline actions that isolate the U.S. from global trade. As Senator Orrin Hatch stated in March, “ While China’s leaders and America’s protectionists have different motives, they have the same ultimate goal: American retreat from open markets and global economic leadership.”

Consequently, if the current Congress can’t resolve its fundamental disagreements with the Administration, it may decline to renew TPA. It can do this through the formal Extension Disapproval Resolution. Or it may simply decline to act, since Congress is legally permitted to use more days to consider the resolution than there are session days left in the Congressional calendar, they can run out the clock. Another measure available to Congress would be to do a NAFTA-specific suspension of Trade Promotion Authority. Nancy Pelosi’s Democrats did this to the U.S. Colombia-FTA in 2008, under the justification that since Congress makes the rules of TPA, it can always make new ones or suspend old ones.

With Congress adjourning in mid-December 2018, it’s also worth noting that we’ve already passed the deadline to meet the U.S. statutory notification and review periods needed for congress to implement new NAFTA legislation.

A deal without Congress?

I confess that in previous analyses, I under-estimated the extent to which the President can unilaterally change the NAFTA. Although the Constitution requires that any action affecting tariff rates receive Congressional approval, a lot of leeway was left for Executive discretion in the 1994 NAFTA implementing legislation. Former Chief Trade Counsel for the House Ways and Means Committee, Viji Rangaswami, points out that the President can make reforms without Congressional approval in such areas as auto rules of origin, labour and the environment. However, two important areas where the U.S. is seeking significant NAFTA reform are Chapter 19 and textiles and apparel – both of which require Congressional approval to modify – so, in my opinion, an end-run around Congress is unlikely without a significant change to the U.S. negotiating mandate.

And still more Congressional wrangling

There is growing speculation in DC that USTR Lighthizer might consider launching a six-month notice of NAFTA withdrawal after the negotiations are complete, forcing the new Congress to choose between new NAFTA and no NAFTA, rather than framing the choice as new NAFTA versus the status quo. This theory is gaining traction among negotiation watchers but I think this underestimates the likelihood that presidential withdrawal actions will be blocked or delayed by court challenges by U.S. businesses who rely on the NAFTA to support their external commerce.

An agreement in principle but not substance?

With the U.S. and Mexico preoccupied with election dynamics, the U.S. fighting a multi-front war on trade, and Canada and Mexico struggling with continued trade uncertainty. There is speculation that the parties might agree to a deal in principle by the end of April and will continue to work on the technical issues on a separate track. This seems to be a preferred position by the White House. For Canada and Mexico, accepting a deal in principle without commitments on key issues means trading off negotiating leverage in exchange for economic stability.

Canada announced a similar agreement in principle in advance of the final ratification the Canada-EU Free Trade Agreement in 2013, but those negotiations were substantially complete before the announcement was made. Even so, the arrangement still threatened to backfire if one or two differences escalated into major political clashes. Complications did arise and the final deal wasn’t concluded until 2017. For a NAFTA agreement in principle to make sense, the negotiations would have to be close to the finish line. In mid-April, the negotiators appeared to be short of the half way mark with little movement on the most difficult issues.

A complicating factor for Canada arises if Mexico decides to accept the early deal. To this point, Canada and Mexico are aligned on most issues in principle if not in degree. If Mexico defects from this coalition, Canada, loses a lot of U.S. domestic political leverage. Quite frankly U.S. legislators worry a heck of a lot more about Mexico, not only in terms of market access issues but also Mexico’s continued migration control efforts on its southern border with Guatemala.

Issue State-of-Play

One of the upsides of the recent political meetings is that they provided political momentum to accelerate technical working group talks. This has been particularly important for the brainstorming and stakeholder consultation sessions to update auto sector rules of origin. While the U.S. has reduced its regional and national content demands, to be successful, the new system must provide greater origin credits for components requiring higher-skill/higher-wage labor inputs (theoretically shifting a greater percentage of production out of Mexico).

Working groups have also continued discussions on competitiveness, temporary entry of business people, state-owned enterprises, the environment, investment, services (including financial services), and labor. As outlined in previous updates, issues like competitiveness and state-owned enterprises which were updated in the TPP are the easiest to conclude. Issues where there are strong domestic political pressures at play, such as temporary entry and labor, will be difficult to resolve the current uptick in political attention.

What remains most uncertain are the so-called poison pill issues such as the sunset clause, dispute settlement, and government procurement – U.S. proposals that Canada and Mexico see as significantly diminishing the value and effectiveness of NAFTA.

A political flashpoint for the U.S. is access to the Canadian market for dairy. Under the Harper government Canada began to offer progressively higher levels of dairy market access in trade agreements, leading to predictions of the eventual reform of the supply management system. There is no reason to believe that the Trudeau government has departed significantly from this trajectory. However, Canada will want to be ‘paid’ for concessions in this highly sensitive sector by gains elsewhere. These sorts of trade-offs usually take place in the final stage of negotiations, once political decision makers have a chance to assess the net benefits offered by the agreement as a whole and domestic political receptivity to reform.

Other issues that Canada considers to be important but difficult are trade remedies, dispute settlement, labor, government procurement, temporary entry for business people, streamlined processing for low value shipments (de minimis) and new rules on third-party liability for digital service providers (safe harbor). Red line issues for Mexico are investor-state dispute settlement, and no new restrictions on textiles and apparel or perishable produce.

Finally, issues that are administratively complex but non-controversial have been moved to technical level working groups, including market access for non-protected goods and agriculture, sectoral annexes, services, currency, investment, labor, environment, financial services, energy, legal and institutional measures and state-owned enterprises.

Don't Bet on a Quick Conclusion

If the NAFTA 2.0 negotiations were following a traditional pathway, I’d expect another nine months or so of technical talks. During the past three weeks, the technical discussions have been accelerated and compressed as a result of political pressure. This has generated real progress. The challenge, however, is that moving off the traditional pathway and accepting a deal in principle assumes a successful final outcome and reduces negotiating leverage by denying any negotiator the right to leave the table.

A secondary challenge is that the parties will only consider the deal-in-principle option only if their most important issues are resolved, but the priorities for each party are sometimes starkly different. Moreover, the costs and benefits of the deal are dispersed by sector and by region. Minister Freeland cannot return home with a great deal for dairy but nothing for autos and timber. The real ‘art of the deal’ is achieving the fine balance between costs and benefits with trading partners and doing the same with domestic constituents. Leaving the table too early makes these trade-offs impossible to achieve.

Despite all the theatre of the past weeks, Canada external message has been consistent. While it is willing to remain at the table to explore all possible options for settlement, it is not willing to accept a NAFTA-minus outcome.

Author

Executive Director, Future Borders Coalition

Canada Institute

The mission of the Wilson Center's Canada Institute is to raise the level of knowledge of Canada in the United States, particularly within the Washington, DC policy community. Research projects, initiatives, podcasts, and publications cover contemporary Canada, US-Canadian relations, North American political economy, and Canada's global role as it intersects with US national interests. Read more

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

USMCA Resource Page

Water Security at the US-Mexico Border | Part 1: Background