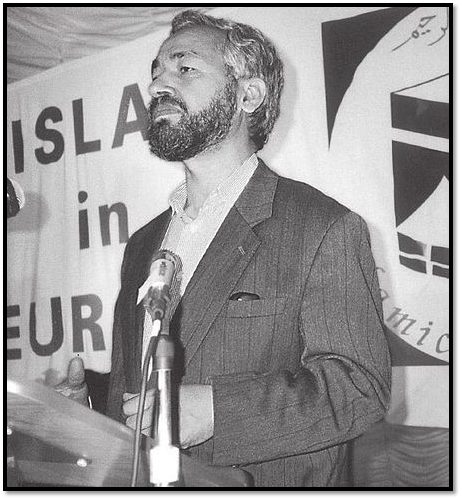

Rachid Ghannouchi’s Thoughts & Career

Profile of the founder of Tunisia's Ennahda Party

Profile of the founder of Tunisia's Ennahda Party

Rachid Ghannouchi, founder of Tunisia’s Ennahda Party, has represented a progressive strand of Islamist thought since the early 1980s. Born in 1941 into a poor farming family, his early life was shaped by the anti-colonial and Arab nationalist movements spawned by Nasserism in Egypt. Government reforms, introduced in 1961, barred religious education at Zaytouna University, where Ghannouchi was a student. He grew disenchanted with Tunisia’s strict secularism, which he viewed as an extension of French colonial influence.

Twice imprisoned in the 1980s, Ghannouchi went into exile for more than two decades. In London, he articulated ideas about how Islam and democracy could coexist. He returned to Tunis after the Arab Spring uprising ousted President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011. He encouraged Ennahda to work in coalition governments after successive democratic elections. In 2019, he became speaker of the National Assembly. He and Ennahda came under growing pressure, however, after the rise of President Kais Saied. The following is a compilation of Ghannouchi’s thinking on major topics as well as a timeline tracking his career.

June 13, 2016: “You have to distinguish between a political institution and a religious one,” Ghannouchi said. For example, mosques must not be an arena of confrontation between political parties. Mosques have to unify the Muslim community, not to divide it. We have to avoid any political propaganda within mosques. Politics push people to compete for wealth, power, and this is what we have to avoid.”

June 13, 2016: “Islam is our reference point. It’s the inspiration, but we don’t ask people to elect us because we are more religious than others.” Ghannouchi said. “We would like to attract people to our movement regardless of their religiosity. All Tunisians are able to join our party, if they accept our program and our program is not based purely on religion. It's based on giving real services to people, real solutions to solve their daily problems. To provide education, good health-care, and create jobs.”

June 13, 2016: “We advise all Islamists in the region to be more open and to work with others and to look for a consensus with others, because without national unity, without national resistance against dictatorship, freedom cannot be achieved,” he said. “There needs to be a genuine reconciliation between Islamists and secularists, between Muslim and non-Muslim. Dictatorship feeds off confrontation between all parties. This only leads to chaos and civil war, where no one will be the winner and everyone will be a loser.”

Jan. 28, 2019: “Protest is a normal and accepted thing within democracy, unlike the general strike in 1978, which Tunisians still remember with great pain and in which hundreds of Tunisians died,” Ghannouchi stated in an interview.

Oct. 13, 2022: “These elites failed to benefit from the fruits of democracy, and so they do not see any good in democracy as long as there is a genuine movement that they failed to defeat democratically,” Ghannouchi said in a statement. “They prefer to get rid of Ennahda rather than resist tyranny.”

2015: Blasphemy is “forbidden in Tunisia, although freedom of conscience and opinion are protected by the Constitution,” Ghannouchi said. “You have the choice to be Muslim or not, but you don't have the choice to mock the beliefs of others.”

June 13, 2016: “Daesh [ISIS] is one of the elements within political Islam, so I would like to distinguish myself from Daesh,” Ghannouchi said. “I am a Muslim democrat, and they are against democracy. Daesh considers democracy as haram (forbidden). There are many deep differences between us and Daesh. Daesh. They are Muslim. I cannot say that they are not. But they are criminals. They are dictators. Daesh is another face of dictatorship. Our revolution is a democratic revolution, and Islamic values are compatible with democracy.”

Jan. 28, 2019: “The Islamic militants [al Qaeda and Islamic State] failed to take any piece of Tunisian territory to make it theirs, Ghannouchi said. “They managed to carry out some attacks here and there, but they immediately withdraw.”

“The notion of state is very deep in Tunisian society and the government is making a huge effort to combat terrorism. We do not have any historical experience of combating terrorism, yet the security and armed forces are making real progress in beating back and defeating these groups, and these groups are now in a defensive posture. We benefited from external support from the European Union, the United States and Algeria, among others.”

Jan. 28, 2019: In an interview with al-Monitor, Ghannouchi spoke on accusations against Ennahda relating to extremism. “We are in an electoral year and there are many accusations against Ennahda…But these are part of a media war that is designed to influence public opinion. It was the Ennahda government which declared Ansar al-Sharia to be a terrorist group and took action against them.”

Oct. 27, 2022: “Jihad as not aimed at imposing Islam on non-Muslims, but rather aimed at defending Muslims Muslim lands against colonization,” he said at a book launch.

May 1, 1980: “The ownership of agrarian property is social in nature,” Ghannouchi said in a speech to labor movements. “The function of such ownership is to serve the community, and therefore those who have been given the right to ownership may lose it. The Ummah (Muslim community) has the right to strip it of them if they fail to dedicate it in the service of the community.”

Jan. 30, 2011: “In the economic sphere Islam is closer to the left-wing outlook, without violating the right to private property, Ghannouchi said in an interview. “The Scandinavian socio-economic model is closest to the Islamic vision.”

July 30, 2021: “More than a decade ago, Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian fruit and vegetable vendor, set himself on fire and became the catalyst for the Arab Spring protests,” Ghannouchi wrote in The New York Times. “Here in Tunisia, his actions helped bring about the end of over five decades of dictatorship, which were marked by endemic corruption, repression of dissent and economic underdevelopment. Today’s unrest is not a quest for freedom, but dissatisfaction over economic progress.”

Oct. 4, 2022: “Tunisians’ expectations were so high after the revolution with respect to economic gains,” he said in an interview. “However, the harvest was not good for many.”

1980: Ghannouchi emphasized the need for women to train as Islamic leaders to “set the example in embodying the values of Islam.” Their contribution “in the pursuit of a comprehensive Islamic renaissance would be invaluable,” he wrote an essay.

Oct. 12, 2012: “In three different places, the constitution states that equality between men and women is guaranteed,” Ghannouchi said. “While there is complementarity between women and men in the family setting, it doesn't mean one is better than the other, or has more rights or responsibilities.”

2015: “Inheritance does not reflect the value of women versus men,” Ghannouchi said.“They are equal in terms of their human value, but don't have the same rights and responsibilities in society.”

Jan. 28, 2019: “The country needs more youthfulness and more women in politics,” he said.

Dec. 10, 2020: “The rights and accomplishments of Tunisian women are a red line that should not be crossed,” he told a press conference.

2015: “We don't approve. But Islam does not spy on folks. It preserves privacy. Everyone leads his/her life and is responsible before his/her creator,” he said.

1962: Ghannouchi graduated from Zaytouna University with a diploma in theology. Under Bourguiba, Zaytouna was increasingly Westernized and its graduates ostracized. Ghannouchi recalled that “For us, the doors to any further education were closed since the University had been completely Westernized,” in a 1985 interview.

1964: Influenced by Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser’s call for Arab unity and pan-Arabism, Ghannouchi moved to Cairo to study at the University of Cairo’s agricultural school. The same year, he moved to Damascus, Syria after relations between Bourguiba and Nasser improved. He studied at Damascus University until 1968. He moved away from Nasser’s Arab Nationalism, believing that Nasser’s ideology was anti-Islamism. “Arab nationalism in North Africa is not contradictory to Islam, becoming Arab nationalist or Islamist is the same,” he said.

1968: Ghannouchi studied philosophy at the Sorbonne in Paris, where he was influenced by Jamaat al Tabligh (or the Preaching Group) from Pakistan. Its members focused on dawa, or proselytizing Islam. He became one of their imams in a poor Parisian suburb. That year, Ghannouchi witnessed countercultural student protests and mass strikes. Ghannouchi saw the political unrest in France as evidence that Western civilization was not inherently superior.

1969: Ghannouchi returned to Tunisia.

1970: In 1970, Ghannouchi and Abdelfattah Mourou joined the Quranic Preservation Society. They hoped to restore Islamic notions of piety and morality in an increasingly secular and Westernized Tunisia.

April 1972: Ghannouchi, Hmida Ennaifer, and Abdelfattah Mourou founded al Jamaah al Islamiyya (The Islamic Group), which rejected Bourguiba’s secularization of Tunisia. They held their first meeting in Tunis.

1978: Ennaifer quit al Jamaah al Islamiyya over the increasing influence of the Muslim Brotherhood on the group. “Early on,” Ghannouchi later reflected, “We were influenced by thinkers in Egypt and Syria linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, such as the movement’s Egyptian founder, Hasan al Banna, and Mustafa al Sibai, the leader of its Syrian branch.”

June 6, 1981: Ghannouchi announced the formation of the Islamic Tendency Movement (MTI). Its manifesto committed to the democratic pluralism and power sharing in government. In July, the government arrested thousands of MTI members, including Ghannouchi. Although he was sentenced to 11 years in prison, Ghannouchi only served four. He continued to lead MTI after his release.

March 1987: Ghannouchi was imprisoned for allegedly leading an Iranian-backed plot to overthrow the Tunisian government. Bourguiba pushed for the death penalty, but the court yielded to international pressure, and Ghannouchi was sentenced to life in prison.

Nov. 7, 1987: Zine El Abidine Ben Ali took power in Tunisia in a bloodless coup, ousting Bourguiba. He promised democracy, reforms, and reconciliation with Islamist movements.

May 14, 1988: Ghannouchi was granted amnesty and released from prison by the Ben Ali government.

1988: In his book titled “Muslim Women in Tunisia,” Ghannouchi advocated for the role of women in Islamist politics and criticized his movement’s earlier position on women. He called for equality between the sexes and the necessity of involving women in all political and social activities. He also emphasized the need for women who were trained as Islamic leaders. Women would “set the example in embodying the values of Islam and whose contribution in the pursuit of a comprehensive Islamic renaissance would be invaluable,” he wrote.

1989: MTI was renamed Ennahda (or the Renaissance Party). Although the party didn’t win official recognition, members competed in the 1989 local elections through independent lists. Ennahda’s members won 15 percent of the vote, including nearly 30 percent in urban areas. Its success led to a government crackdown. The party was banned.

Apr. 11, 1989: Following Ennahda’s political success, Ghannouchi fled Tunisia. He went first to Algeria, and later to London where he spent most of 22 years in exile.

1993: Azhar Abaab, the Ennahda representative in France, resigned after accusing Ennahda leaders of failing to follow “moderate and rational politics” and of pushing “the movement into a vicious circle of confrontation with the regime.”

1993: While in London, Ghannouchi published Public Freedoms in the Islamic State, which outlined the role of citizens in an Islamic State. The public, he wrote, is “responsible for the way that the divine law is interpreted and applied.”

2002: Ghannouchi articulated a vision for Tunisia based on the Moroccan model that would allow Ben Ali to remain the head of state but open the door to modest political reform.

2005: Ghannouchi and Ennahda began working with a broad spectrum of exiled activists, including secularists and leftists, to craft the “October 18 Coalition for Rights and Freedoms.” The joint statement called for constitutional democracy, a secular state, and the embrace of basic human rights.

2007: While in exile, Ghannouchi moved towards compromise with the Ben Ali regime. Ennahda’s Eighth Party Congress, held in London, called for “comprehensive national reconciliation without excluding anyone.”

Jan. 30, 2011: Ghannouchi returned to Tunisia from London after the fall of Ben Ali who stepped down on January 14, 2011 after weeks of the Arab Spring protests, which became known as the Jasmine Revolution.

Oct. 20-22, 2011: Ennahda won the largest number of seats–89 out of 217–in the first parliamentary elections after Ben Ali’s ouster. On November 21, it formed an agreement with the Ettakol Party (20 seats) and Congress for the Republic Party (29 seats).

December 2011: Ghannouchi addressed the need for the coalition government. “We don’t want the people to perceive that they have moved from a single party dominant in the political life to another single party dominating the political life,” he said. Ennahda sought to maintain a parliamentary system that would limit any party from seizing power while guaranteeing “freedoms: personal freedoms, social freedoms, and women’s rights.”

March 2012: With the support of key Ennahda members, Ghannouchi rejected adding Islamic law in a new constitution.

July 2012: Ghannouchi was reelected leader of Ennahda at the Ninth Party Congress, which revealed divisions over the party’s direction after the Tunisian revolution.

Sept. 14, 2012: Islamic extremists attacked the U.S. Embassy in Tunis. Ghannouchi described the violence as un-Islamic. “Their ideas are wrong,” he said.

November 2012: Ghannouchi asserted that Salafis were a minority in Tunisia. Ennahda leaders had convinced Salafi members of parliament not to mention Sharia law in the new constitution. The government needed to encourage Salafis “to work in an organized and lawful way.”

February 2013: “Islam is not fighting against democracy or human rights Islam is mercy and justice,” Ghannouchi said. “We strongly believe that Islam, democracy and human rights are compatible.”

June 2013: In a speech in Cairo, Ghannouchi warned against “democracy where only the majority enjoys privileges and freedoms.” He emphasized the necessity of power-sharing in politically diverse societies.

August 2013: Ghannouchi vowed that the government would not support a law to prevent officials who served under Ben Ali from holding public office for seven years.

October 2015: Ghannouchi rejected ISIS as a model for Tunisia. The solution to extremism lay in a political system that was democratic but allowed Islam and its values to have political space. “The only way to truly defeat ISIS is to offer a better product to the millions of young Muslims in the world,” he said.

February 2016: Ghannouchi outlined a framework to fight the ISIS ideology based on Tunisia’s democratic experience and using a localized approach to counter the jihadist narrative.

May 2016: At Ennahda’s Tenth Party Congress, Ghannouchi announced the end of proselytizing (or dawa). “Our objective is to separate the political and religious fields,” he wrote in an essay. “Ennahda is now best understood not as an Islamist movement but as a party of Muslim democrats.”

April 2018: Amid protests sparked by an economic crisis and high youth unemployment, Ghannouchi stated that the country needed a technocratic, national dialogue.

July 2020: Five political parties sought to oust Ghannouchi as parliamentary speaker, with the Free Constitutional party (CPR) accusing him of catering to the Muslim Brotherhood, Qatar, and Turkey.

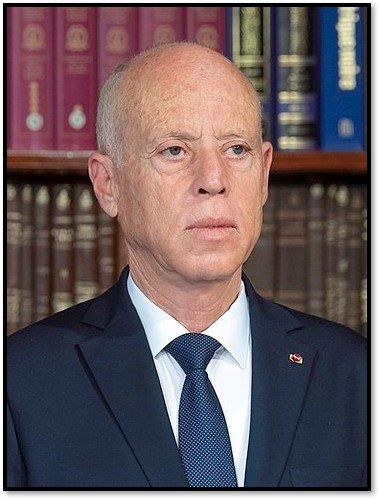

July 2021: President Kais Saied invoked Article 80 of the constitution, which empowered him to take actions to maintain security and “protect the normal operation of state institutions.” Ghannouchi called it a “coup” and an assault on Tunisia’s democratic values.

July 25, 2022: Tunisia held a referendum on a new constitution. Ghannouchi charged that Saied “feels that he is the envoy of divine providence. If we were to have the option to choose between a constitution full of Islamic meanings and a constitution free of them but democratic, we are with democracy.” The State Department criticized “the suspension of constitutional governance, consolidation of executive power, and weakening of independent institutions have raised deep questions about Tunisia’s democratic path, both in Tunisia and internationally.”

Sept. 19, 2022: Ghannouchi was questioned at a police station about accusations of money laundering and links to terrorism. Ghannouchi denied all charges made against him.

Oct. 13, 2022: Ghannouchi challenged Saied’s claim to power. “With his coup against democracy, he has lost whatever legitimacy,” he said.

Nov. 10, 2022: Ghannouchi appeared in court on charges of money laundering and incitement to violence. He denied the allegations and called them “politically motivated.”

Nov. 28, 2022: Ghannouchi appeared in court on charges of “exporting terrorism.” He was implicated in a case involving Tunisians who went to fight in Iraq and Syria. Ghannouchi denied the charges.

April 17, 2023: Police arrested Ghannouchi at his home in Tunis. Ghannouchi was taken to "an unknown location," according to an Ennahda's statement. The statement condemned his arrest and called on "all freedom-loving people to stand together in the face of these repressive practices that violate rights and freedoms and the dignity of opposition politicians." The European Union said that it was monitoring the situation "with great concern." The U.S. State Department condemned Ghannouchi's arrest, calling it “fundamentally at odds with the principles Tunisians adopted in a constitution that explicitly guarantees freedom of opinion, thought, and expression.”

April 18, 2023: Tunisian authorities announced a ban on all meetings and activities at Ennahda's offices. "It seems to be an attempt to ban the Ennahda and hit opposition,” said Riadh Chaibi, a senior party official.

April 20, 2023: A judge ordered that Ghannouchi be placed in jail ahead of his trial. The decision was reportedly made after eight hours of investigation. "It was a ready decision to imprison Ghannouchi only because of Ghannouchi’s expression of his opinion," said Ghannouchi's lawyer. Ennahda said that the move was politically motivated in a statement posted to its Facebook site.

May 15, 2023: A judge sentenced in absentia Ghannouchi to one-year in prison and fined him for remarks he made at a funeral in February 2022. In a eulogy, Ghannouchi lauded the deceased, a member of Ennahda, for not fearing “a ruler or tyrant.”

Sept. 5-6, 2023: Tunisian authorities detained Ennahda’s interim President Mondher Ounissi and Abdelkarim Harouni, the Shura council head on September 5. The next day, they questioned former Ennahda official and Prime Minister Hamadi Jebali about “appointments and missions during his tenure” from 2011-2013, according to media. Ennahda condemned the “malevolent campaign” meant to “[hurt] the Islamist movement and its leaders.”

Aaron Boehm, a research assistant at the Wilson Center, compiled this report.

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more