The role of environmental conditions in triggering migration has long been hotly contested. Climate change as the definitive condition is no exception. How exactly climate change impacts forced or voluntary migration is difficult to decipher and riddled with complexity, yet the essence of climate change is that it is marked by a dramatic and decisive departure from the past. Despite the inconclusive and sometimes contradictory historical record for the environment-migration nexus, it is clear that climate change will increasingly influence migration patterns around the world. Estimates for how many people will move as a result of climate change are wide-ranging and fraught with uncertainty. What we do know is that migration is an important factor in climate adaptation, for both sending and receiving countries.

The actions that have led to climate change and its impacts (migration chief among them), and the geographically lopsided nature of them, make “climate change” as much a geopolitical term as a scientific one. To date, however, diplomacy related to climate change has been generally relegated to environment ministers, climate negotiators, and scientists who are tasked with managing a phenomenon with geopolitical implications. Those engaged in other areas of diplomacy have not seen its relevance to their portfolios. Many within the diplomatic class, such as trade envoys, actively disregard or oppose climate change curbing goals, despite the consequences for the globe and their very remit.

The effect of this positioning is that climate and environment negotiators, armed with the limited capacity and resources to “manage the trees,” are now burdened with saving each and every forest, as well as the peoples and political economies that depend upon them (i.e., the global population). Consistent with the intent of the “21st Century Diplomacy” project, Sue Biniaz persuasively argues the same in her article, reminding fellow diplomats that “it’s your problem too” and “climate is foreign policy,” both militating in favor of intentional and intensive streamlining of climate change in diplomatic work.

Climate migration touches on innumerable areas across international law, and down to domestic and sub-national decision-making. Notably, climate-induced migration breaks through the typical silos more so than the impacts of climate on other sectors, like agricultural productivity, transportation, and energy. This is in part because climate-induced migration is commonly used to illustrate how climate change can act as a “threat multiplier.” Without additional context, however, the (unintended) consequence of this framing is that it presents climate-induced migration first and foremost as a security risk. It obscures the very practical role that migration plays in climate adaptation, and the need and potential for interventions that prevent forced displacement—that is, interventions that allow people to decide whether or not to move.

This piece surveys relevant evidence and current policy proposals related to climate change and migration, explores the shortcomings of the predominant security framing, and seeks to inspire and advance diplomatic responses that provide meaningful choices for those at the crossroads of climate change and human mobility.

Climate Migration – Evidence and Projections

Although experts are quick to maintain that migration has always been a feature of human behavior and the product of multiple drivers, climate change is increasingly a factor in the decision to move. Perhaps the clearest indication of this is the growing number of people displaced by weather-related impacts. In fact, weather related displacement now represents a significantly larger number of internally displaced people (IDPs) than those displaced by conflict and violence. In 2017, there were 18.8 million new IDPs associated with disasters, compared with 11.8 million new IDPs as a result of conflict and violence.

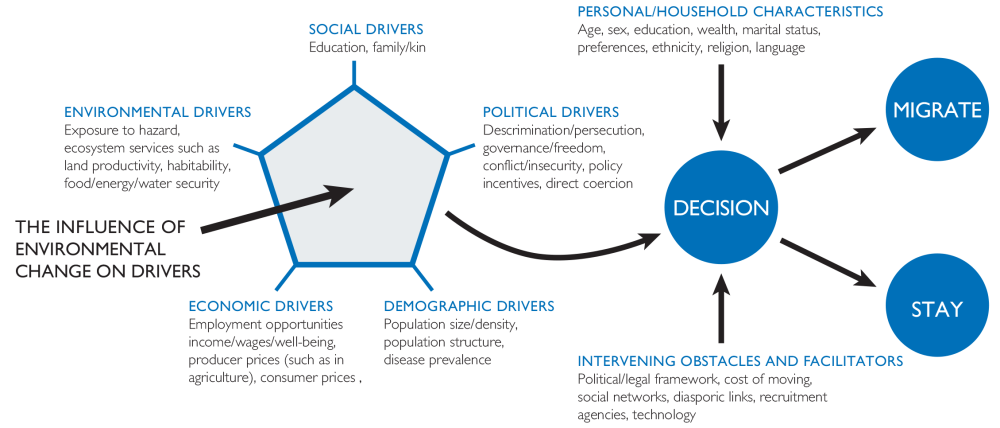

Climate change will also impact migration through its effects on the five broadly recognized drivers of migration: economic, political, demographic, social, and environmental. Together these drivers comprise a conceptual framework for deciphering the range of factors that might affect the volume, direction, and frequency of migratory movements. Climate will redistribute economic activity and shift trade routes, impact agricultural productivity, expose weak governance in fragile states, and deepen inequities. As climate change impacts the primary drivers of migration, its influence on migration decisions and pathways will grow.

Climate change will also influence mobility patterns more directly, however, as global change increases sea level and the number and intensity of droughts, floods, heatwaves, and other extreme weather events. There are, of course, variations in the responses to these triggers. Sea level rise, for example, is more likely to influence the timing and volume of ongoing migration rather than produce novel patterns of migration. Migration responses and displacement as a result of extreme, sudden onset events vary widely across socioeconomic groups, as seen in the United States following Hurricane Katrina. Droughts and extended extreme heat events suggest wholly different patterns. Where livelihoods and food security are undermined, but homes left intact, these events do not generally lead to “immediate, large-scale displacement or migration.” However, if the conditions persist and there is insufficient adaptive capacity, internal rural to urban migration may increase. These divergent responses, under varying scenarios, make a precise prediction of the scope and scale of climate-induced migration a fundamental challenge. [See further information on evidence of climate-migration linkages around the world.]

Three broad, possible shifts in mobility due to climate change can be deduced, however:

- Larger flows of people along established migration routes as the destinations become safer or more attractive, sending areas become less safe or less viable, and migration network effects continue to facilitate movement.

- Unchanged or even decreased flows of people along established migration routes, either because destinations become less attractive or less viable relative to the sending area, or because migrant networks are not able to facilitate greater levels of migration.

- New flows of migrants between sending and destination areas that have not historically been connected, leading to the creation of new migration networks.

Given the way in which recent migration crises have unfolded, countries—including those in the Global North—are woefully ill-prepared. In an assessment of “distress-driven migration,” researchers found that climate change could drive a huge increase in the number of migrants seeking asylum in Europe if current trends continue. They forecast the number of migrants attempting to settle in Europe each year to triple by the end of the century based on current climate trends alone, independent of other political and economic factors. Warming of 2.6 degrees Celsius to 4.8 degrees Celsius (which climate experts deem likely unless stringent measures are taken to bring down greenhouse gas emissions) would result in as many as 660,000 additional asylum seekers coming to Europe each year by 2100, based on their proposed model.

Numbers like these dominate the climate migration discourse, with estimates of global climate migration ranging from as few as 25 million to as many as 1 billion climate migrants. These numbers can tell a compelling story but are hampered by the limitations of crude population estimates and fail to consider the countering effects of climate adaptation, particularly to facilitate potential migrants’ preferences to stay in place. They also leave out the stories of those unwilling or unable to relocate, sometimes referred to as “trapped populations.” Of equally great concern is the absence of broadly recognized and formal legal infrastructures and clearly articulated and enforceable rights of migrants, much less a spirit of readiness and welcome for receiving countries.

The focus on the projected number of potential migrants obscures another important fact: Migration is a critical and long-practiced resilience strategy with benefits for both sending and receiving communities. In fact, as a response to climate change, it may serve as “the most effective way to allow people to diversify income and build resilience where environmental change threatens livelihoods.” Temporary migration can be a necessary and pragmatic response to disasters, and is capable of strengthening the resilience of affected communities. Migrants often provide significant remittances to their places of origin, increasing the resilience and adaptability of those who remain. In 2019, for the first time, remittances exceeded foreign direct investment and official development assistance flows to low- and middle-income countries.

These potential benefits of migration, however, are dependent on policies that facilitate safe, affordable, and legal migration, ensure equal rights for both migrants and host communities, and avoid real or perceived disparities in opportunity or access to services between migrants and host communities. Decision-makers should institute these migration policies in concert with broader climate strategies such as aggressive decarbonization, sustainable urbanization, climate-smart development, conflict resolution and prevention, and emergency preparedness.

Relevant Laws & Governance Gaps

The instruments and regimes related to migration that are currently in place fail to respond effectively to current migration flows, and increased and potentially erratic movement will likely further stress and strain them. In short, the mobility options for those on the move are circumscribed by increasingly antiquated 20th century parameters. They include: a move to (the rare) neighboring country that allows unrestricted entry; formal international migration programs that facilitate entry to high-income countries, such as a skilled worker visa programs; and the extralegal, clandestine, and often life-threatening journey to another country to seek asylum.

Most climate change and mobility scenarios fall outside of almost all legal frameworks, prompting numerous and sustained calls for a global governance regime to manage international migration. Some have called for a new legal instrument, such as a standalone treaty to address cross-border climate-induced migration, while others remain skeptical that migration spurred by climate change differs substantially from other kinds of survival migration to warrant a new instrument—never mind the difficulty of drafting and passing a new one or amending the Refugee Convention.

Certain migration scenarios may meet the elements of the oft-invoked Refugee Convention’s definition of “refugee.” If authorities were to deny assistance and protection following a slow or sudden-onset event to “certain people because of their race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion and as a consequence expose them to treatment amounting to persecution,” protections might be available. The overwhelming consensus, however, is that climate-induced migration, particularly triggered by relatively slow-moving sea level rise, for example, falls outside of the Convention’s scope and protections.

More recent international attempts to manage movement related to climate change include three United Nations initiatives relevant to migration: The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM), the Global Compact on Refugees, and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Task Force on Displacement (Task Force). The Task Force seeks to enhance the capacity of governments and regional and international organizations to address climate-related drivers and impacts of displacement by developing recommendations for integrated approaches in response. Some believe that a combination of extant approaches, if fully taken up, would be effective. The GCM, the Sustainable Development Goals, and the UNFCCC displacement efforts “collectively provide all of the policy-making tools necessary for responding successfully to the risks posed by climate change.” Yet the United States, Australia, and a number of European states did not vote to approve the GCM, despite the fact that it doesn’t create any legal obligations. Meanwhile the current U.S. administration has initiated withdrawal from the UNFCCC’s Paris Agreement and appears thoroughly unmotivated by the goals and content of the SDGs.

International agreements related to the protection of human rights may be increasingly relevant. In 2013, an i-Kiribati man was denied asylum in New Zealand after claiming that, if deported, he faced irreparable harm to his right to life because climate change is rendering Kirabti uninhabitable. In a subsequent appeal, the UN Human Rights Committee found that New Zealand did not violate the man’s right to life when they deported him. In their ruling, however, they recognized that “without robust national and international efforts, the effects of climate change in receiving states may expose individuals to a violation of their rights,” suggesting that future claims based on violation of human rights might be available. There are also relevant principles and soft law provisions, such as the Peninsula Principles on Climate Displacement within States and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, that while pertinent are not binding on any nation state, providing very limited protection for migrants. Some individual nation-states also provide temporary or subsidiary protection for disaster-induced cross-border displaced persons that, while promising, remain ad hoc.

Informing More Effective Diplomatic Responses

Explore State to State Engagement

The diplomatic community might explore avenues adjacent to the multilateral initiatives described above. While there are no legally binding regional conventions or treaties that prescribe obligation for developed countries, existing or newly crafted regional, bilateral, and multilateral agreements may be relevant. And, countries with strong transnational communities can develop bilateral arrangements.

The Compacts of Free Association between the United States, and the “Freely Associated States” of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of Palau, for example, allow for visa free entry to work and live in the United States. These agreements were negotiated before climate related threats to habitability emerged but may, nonetheless, provide an avenue for migration in response to climate impacts. Even so, there are gaps in the existing agreements that, if addressed, would strengthen them. While the agreements do allow for indefinite stay, they do not provide a pathway to citizenship for migrants. The lack of financial assistance restricts eligibility to those with existing resources or family networks. Finally, the Compacts may not serve as an adequate solution to permanent or large-scale population displacement in large part because they are unilaterally terminable by any party.

Regional governance of migration, effectively exemplified by the free movement agreements (FMAs), may offer a more facile, practical response to climate migration and displacement. Such ‘bottom-up’ approaches acknowledge that regions experience climate displacement differently and have differing capacities for protecting those who are displaced. FMAs—provisions within broader regional economic agreements that liberalize mobility restrictions between participating states—have the potential to offer comprehensive protection to climate migrants. They exist across all continents and have already proven effective in facilitating migration in the disaster context. For instance, the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) FMAs were both used during the 2017 Atlantic Hurricane season to provide displaced persons a right of entry into neighboring island nation-states, waivers of travel document requirements, indefinite stays in some circumstances, and access to foreign labor markets by waiving work permit requirements. For instance, after Hurricane Maria in 2017, displaced Dominicans were able to migrate to Trinidad and Tobago using the CARICOM FMA’s six-month visa-free stay program, and others were able to migrate to Antigua, St. Vincent, Grenada, and St. Lucia under the OECS FMA. Expansion of FMAs may provide effective protection in the climate change context.

FMAs may also resonate in the Pacific, as free movement harkens back to pre-colonial Oceania in which islanders’ freedom of movement was not hindered by national borders. Historically, interconnections among islands were inherent to the Pacific experience, “but active travel and resettlement activities were stifled by the migration and mobility restrictions of the colonial powers.” Indeed, current South Pacific negotiations processes seem shaped by these earlier conceptions of mobility when facing contemporary discussion of climate migration. Similarly creative, collaborative, and humane proposals can emerge if the security frame is right-sized to address the multidisciplinary nature of climate change generally, and climate and human mobility specifically.

Loosen the Security Frame and Expand the Toolbox

In the academic literature there is a consistent concern regarding the exceptionalism used to describe climate-induced mobility (as if mobility has not been a defining feature of human history) and the subsequent securitization of climate migration. The larger numbers of potential migrants estimated and disseminated in policy reports are often used to fuel the negative perceptions of migrants themselves, strengthening the “threatened borders” narratives and anti-immigrant sentiment prevalent around the world today. As noted by Boas et al.’s review and reflected in the migration agendas of the European Union, United States, and Australia, among others, the effect of this narrative is that “‘climate-induced migration’ is now a common rationale for measures to strengthen and protect national and regional borders in the Global North.” These countries are implementing migration policies that include restricted entry, discouragement of asylum claimants, and criminalization of undocumented migration—and, in some instances, are pressuring other countries to do the same. This is suboptimal from the perspective of the migrant as well as host countries and communities.

The growth of anti-immigration sentiment and border tightening is also happening within the Global South, where South-South migration is empirically more prevalent and is projected to grow. In Johannesburg last September, a dozen people were killed in a spate of xenophobia-fueled violence against migrant shop owners. Also of note are the stricter border controls Venezuela has erected with its neighbors, the Dominican Republic’s deportation of Dominican-born descendants of Haiti, and Kenya’s border fence with Somalia.

In addition to military grade weapons, vehicles, and even uniforms, high-tech surveillance tools are being deployed by the U.S. Border Patrol. We see increased border surveillance as well in the European Union with the use of biometric visas for third-country nationals. Robert McLeman underscores the stark consequences of this turn:

"…turning these technologies with military origins against civilians … securitizes the act of migration. It blurs the distinction between surveillance actions to detect and deter the approach of armed enemy agents — something that every state has a sovereign right to do — and monitoring borders to prevent the approach of unarmed civilians seeking entry: something every person has a right to do under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UN Refugee Convention. In this collision, the rights of the individual are lost."

These trends carry their own security risks. Migration can act as an important “release valve.” Restrictions on mobility—including hardened borders and the criminalization of asylum-seekers—force migrants into “expensive and physically dangerous attempts to reach their destinations.”

Severely impeding mobility can have knock-on effects on livelihood security more broadly, and not just in regard to remittances. For example, in the Lake Chad Basin, where more than 2.5 million people have been displaced by conflict and 10.7 million are in need of humanitarian assistance, an assessment of the region’s climate and fragility linkages found that "restrictions on the places that people can live and travel [compound] the impacts of displacement and population growth on livelihoods and natural resources."

A reorientation that does not reinforce decontextualized narratives about climate-fueled mass migration is sorely needed at this time. A narrative that is focused on both the risks faced by affected populations’ and their rights, and is as attentive to the need to migrate as it is to efforts to “stay in place,” will be the most effective. It is only through this reorientation that policymakers and practitioners will be able to identify an expanded set of entry points for interventions that bolster the resilience of both sending and receiving communities.

Conclusion

The single defining global policy decision regarding human mobility and climate change is the rate of greenhouse gas emissions and their rapid drawdown. But the fact remains that even if greenhouse gas emissions were reduced to zero tomorrow, the world would continue to warm for several more decades.

The rhetoric needs to shift from a fear of migrants and unregulated migration to one focused on the impact of investing in countries experiencing high levels of displacement and the facilitation of safe and sanctioned movement for those who need it most. To allow those who are at the climate and mobility crossroads to enjoy meaningful choices, the diplomatic community will need to facilitate the protection of life and dignity, whether individuals and communities are on the move or choosing to stay in place. Key to this is the recognition of the role played by domestic and international institutions, agencies, and international regimes that are tasked with addressing and responding to the increased movement of people across and within borders.

We must address the magnitude of 21st century human migration, which has no historical analogue, by crafting solutions that are not shaped by, nor perpetuate, fear and othering. Instead, mediated approaches that are inclusive and rights-driven should be the only non-negotiable.

Evidence of Climate-Migration Linkages Around the World

The interplay of climate migration drivers is born out in the results of studies on migration in West Africa. One review examined 15 empirical case studies that concentrate directly on the links between climate and human mobility in West African drylands. The authors found that the studies were consistent on three points: 1) environmental conditions and changes tend to result in temporary migration; 2) migration is commonly leveraged to diversify income; and 3) migration is caused by multiple factors. They also determined that environmental factors are often not the main driver but can trigger movement in regions where there are other drivers at play. Again, however, whether the future stays consistent with current and former studies is unclear in light of accelerating climatic changes.

Increased temperature may have a more significant impact on migration as it can more directly, and more permanently, impact those whose livelihoods are dependent on the environment (e.g., declines in agricultural productivity). A 21-year longitudinal survey conducted by Mueller et al. in rural Pakistan that measured the relationship between weather and long-term migration found that while flooding—a climate shock commonly associated with large relief efforts—has “modest to insignificant impacts on migration,” heat stress “consistently increases the long-term migration of men, driven by a negative effect on farm and non-farm income.” Interestingly, they explain that flooding’s more modest impact on migration may be because flooding increases demand for local labor and hence reduces migration.

Similarly, Bohra-Mishra et al. demonstrate that increased temperatures have had a much stronger effect on inter-provincial migration within the Philippines than disasters by using a detailed longitudinal data-set, combined with data on temperature and precipitation. Another study by Feng, Krueger, and Oppenheimer found that climate-driven changes in crop yields in Mexico had a significant effect on Mexican emigration to the United States.

Authors

Environmental Change and Security Program

The Environmental Change and Security Program (ECSP) explores the connections between environmental change, health, and population dynamics and their links to conflict, human insecurity, and foreign policy. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Can Climate-Resilient Agriculture Become an Engine for Syria’s Post-Conflict Recovery?

ECSP Weekly Watch | March 10 – 14

ECSP Weekly Watch | February 17 – 21