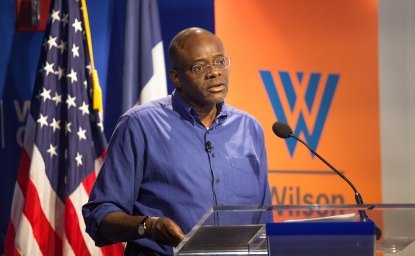

Arnaud Kurze: Transforming Justice from the Bottom Up

Global Fellow Arnaud Kurze shares his insight on the dynamic field of transitional justice and how marginalized voices are amplifying and answering calls for action.

A blog of the Wilson Center

Global Fellow Arnaud Kurze shares his insight on the dynamic field of transitional justice and how marginalized voices are amplifying and answering calls for action.

Arnaud Kurze, Global Fellow with the History and Public Policy Program, is Assistant Professor of Justice Studies at Montclair State University. In addition to his scholarly work on transitional justice in the post-Arab Spring world, he is currently leading a Digital Humanities Project on political change in the Mediterranean basin and is co-organizing the Cres Summer School on Transitional Justice. He is widely published and the editor of New Critical Spaces in Transitional Justice: Gender, Art & Memory. He is the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships, including the American Council on Learned Societies and Sciences Po.

Q: What does transitional justice look like in the 21st century?

A: Transitional justice -- or in other words, how we as a society account for past wrongdoings -- has greatly changed over the years. More precisely, it has expanded its repertoire drastically recently. While efforts to deal with the past were initially centered around several traditional pillars, including retributive as well as restorative justice mechanisms, ways to address mass atrocity and grave human rights violations have shifted over time and include new forms of reckoning. It is not only governments or official institutions that are at the heart of these efforts, but civil society has also increasingly become front and center in implementing these efforts. I am currently writing the final pages of a book on Youth, Art and Resilience, which maps these tectonic changes of how societies can best deal with their dark pasts. It features a new generation of actors, namely youth activists, as well as art as a vector to implement this type of change.

Q: Your recent research focuses on comparing the performative activism in younger generations with the work of older human rights organizations in the Balkans and the MENA region. What are the main differences you’ve noticed between the two generations in these regions, and how might these distinctions apply to other countries’ transitional justice processes?

A: The young generation of activists have a broader transnational network than their predecessors. Moreover, social media and internet technology have also enabled different groups of social actors to stay connected and learn from other similar cases abroad. Older generations of human rights activists -- while promoting rights and freedoms -- were more vulnerable to authoritarian state apparatuses. The revolutionary uprisings of the Arab Spring have illustrated how newly empowered activists were able, at least temporarily in many cases, to defy state authorities. More recent examples of protests in Hong Kong, exemplify this trend. Unfortunately, state authorities do not remain inactive and have learned their own lessons, as for instance Egyptian president Fattah el-Sisi or Chinese president Xi Jinping. Both have cracked down on activists' demands for rights, freedom and accountability. It remains to be seen (albeit the likelihood is low) whether external forces, such as great powers, will intervene effectively to support civil society demands.

Q: Since starting your work on transitional justice, what is the greatest change you’ve seen in the field?

A: Over the past decade we have witnessed a tremendous increase in bottom-up activities. This does not necessarily signify that they were inexistent previously, but technology has enabled to increase the visibility of these community-led initiatives. As a consequence, international institutions have noticed these trends and this, in turn, has led to further empowerment of vulnerable or marginalized groups, including youth, women, and sexual minorities.

Q: You mentioned in your Wilson Center NOW interview that you focused on gender, art, and memory in your book because those angles were largely ignored in the general discourse. What are other angles to transitional justice that you’ve explored in your research that may be marginalized in the field?

A: These three larger topical areas include a number of related themes that have found less attention and that will have to be tackled in the years to come. I am notably thinking here of race and temporality. The dark chapter of racial injustice that is embedded in our US institutional system is a pressing issue that has been ignored or inappropriately been dealt with in the past. Recent events have shifted the tide and different efforts, particularly grassroots initiatives, have crystallized and given these crucial issues more attention in the public eye and across media platforms.

Q: Could you share any upcoming projects that you’re working on?

A: I am currently working on several projects. As mentioned earlier, I am wrapping up a manuscript that maps alternative transitional justice mechanisms, notably focusing on youth activists, art and collective memory in the context of rising authoritarianism. Furthermore, I am co-writing another book that looks at global justice issues, including timely public health crises and environmental challenges. Lastly, I am also helping to expand the Digital Archive at the Wilson Center to include broader cultural and sociopolitical aspects that have affected our societies. One goal here lies in providing broader access to the materials and digital documents by using visualization tools that increase accessibility and visibility of large amounts of online data.

Q: How has your time at the Wilson Center impacted your research and understanding of your field?

A: The Wilson Center is a very effective and eclectic hub to understand, explore and disseminate important research. Thanks to many stints at the Wilson Center I was able to engage in productive, eye-opening dialogues with scholars, practitioners and lawmakers. As a case in point, I was able to raise early awareness about the importance of youth as an actor of change, rather than the perpetual victim, as they are often portrayed in post-conflict settings. The Center continues to be an important space for ideas and bipartisan discussions that result in progressive policy to foster social and political change.

Q: What has been your favorite project or memory while at Wilson?

A: I fondly remember the collegiality, ample opportunities for intellectual exchanges and the overall, forward-thinking mindset at the Center. Often, scholars and fellows from different focus areas would get together over lunch in the cafeteria and engage in stimulating discussions on current issues or policy debates, which speaks volumes about the importance of cross-disciplinary and bipartisan perspectives when tackling our pressing contemporary global and local problems.

Q: Do you have any advice for a student interested in your field?

A: Since the field has been growing exponentially over the past decade, many local issues have emerged to the forefront. Anyone interested in exploring post-authoritarian and post-conflict justice has now the opportunity to study it in their "own" backyard. While it is important to understand more conventional mechanisms, such as human rights trials or truth commissions, the focus has shifted to alternative transitional justice mechanisms. These include notably the arts as well as performative activism and deserve closer attention, particularly in view of empowering marginalized communities.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more