A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

One day after the announcement of the AUKUS security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States on September 15th, China applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Although China’s admission to the 11-nation trade agreement remains doubtful, the move is representative of Beijing’s push for further economic and financial integration through multilateral trade agreements. AUKUS may very well check Chinese military power projection in the Indo-Pacific by equipping Australia with nuclear-powered attack submarines in a few decades. However, without a corresponding economic dimension, AUKUS allies risk unintentionally inflicting harm on each other as they unilaterally pursue their own economic interests. The consequences of U.S. economic bilateralism will have a more immediate impact on its allies, within AUKUS and beyond, than security multilateralism. The Biden administration needs to complement AUKUS with economic multilateralism in order to more effectively compete with China.

Bilateralism versus Multilateralism

To be sure, U.S.-China economic relations matter for the Biden administration, but overly narrow U.S. conceptualizations of those interests can undermine multilateral efforts such as AUKUS. For example, U.S. Trade Representative Ambassador Katherine Tai recently promised to assess China’s performance under the Phase One Agreement, including its commitments to purchase U.S. products, in upcoming talks with her Chinese counterpart. During a briefing, she artfully dodged a question raised by Daniel Rosen about how to reconcile the Biden administration’s emphasis on working with allies and the centrality of the Phase One Agreement in dealing with China. As Rosen pointed out, China could meet its purchase commitments to the U.S. through trade diversion from U.S. allies like Australia. Purchase commitments to the tune of $200 billion were a major element of the Phase One Agreement signed in January 2020, and China has since fallen short of these ambitious targets. Ambassador Tai promised to “defend-to the hilt-[U.S.] economic interests,” but we argue that the Biden administration must choose between continuing to define these economic interests narrowly, as the Trump administration did, or more broadly to encompass the economic interests of allies when dealing with China.

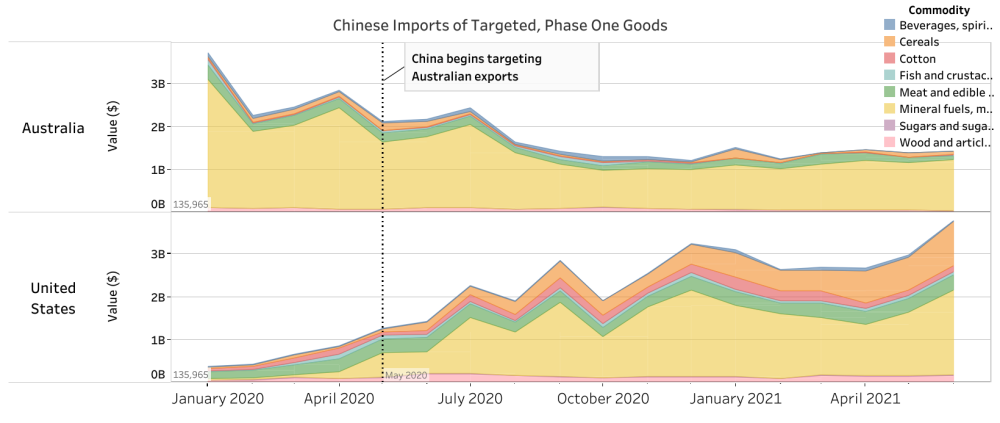

We use product-level trade data to show that China used trade restrictions against Australia as a way to facilitate the fulfillment of Phase One purchase agreements with the United States. While China’s economic coercion of Australia in 2020 was presented by Beijing as defending national pride and addressing grievances to its domestic audience, the Australian products they chose to target reveal a logic of trade diversion to appease the Trump administration. This case study reveals the pernicious effects that managed trade through purchase commitments have on the global economy and why bilateral deal-making with China creates unintended consequences for U.S. allies. As the Biden administration rallies U.S. allies like Australia to confront China militarily, it must also work with those allies to build a common economic front rather than prioritizing its own exporters at the expense of allies.

The Trade Diversionary Logic of China's Economic Coercion of Australia

Since May 2020, over $25 billion of Australian exports have been subject to restrictions put in place by the Chinese government. Implemented just weeks after Australia echoed the United States in calling for an international investigation into the origin of COVID-19, the trade restrictions have been widely viewed as the result of increasingly hostile Chinese attitudes toward foreign policy and an increased Chinese willingness to leverage its position as the world’s largest trading nation to induce political concessions. When asked about trade measures against Australia in July, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian said plainly: “We will not allow any country to reap benefits from doing business with China while groundlessly accusing and smearing China.”

On the surface, recent tensions between Australia and China appear to be rooted firmly in the political sphere. However, this understanding fails to consider that the Australia-China relationship exists not within a vacuum but instead a multilateral network of international trade. Months earlier, China had concluded Phase One Deal negotiations and agreed to increase imports of certain U.S. goods by $200 billion over two years.

However, from the time the deal was reached, there was doubt surrounding the methods used to set the purchase targets and China’s ability to meet such large targets. Trump himself emphasized bilateral trade deals as opposed to regional multilateral agreements, reflected perhaps most notably in his administration’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Then, Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross explained that the Trump administration’s preference for bilateral agreements was based on the logic that they were easier to negotiate for the United States. This ‘America First’ logic and preference for bilateral trade deals necessarily ignores the effects of such deals on U.S. allies.

Our research indicates that China was robbing the Australian Peter to pay American Paul, that is targeting its sanctions against products that would help meet its Phase One Trade Deal purchase targets.

Our research indicates that China was robbing the Australian Peter to pay American Paul, that is targeting its sanctions against products that would help meet its Phase One Trade Deal purchase targets. Of the nine Australian sectors targeted by Chinese sanctions (Beef, Barley, Coal, Copper, Cotton, Lobster, Sugar, Timber, and Wine), only copper was not included in the Phase One Deal. If China truly sought to punish Australia for perceived political transgressions, we would expect it to restrict sectors in which the value of trade with China relative to GDP is greater. In 2019, two-thirds of China’s total imports of iron ore came from Australia. Trade with China in the iron ore sector was worth nearly 4.4% of Australia’s GDP. Rather than inflict greater economic costs on Australia by targeting high-value sectors such as iron ore, China instead targeted sectors where trade could be easily diverted and accounted for a smaller share of Australian GDP.

The figure above shows that as Chinese imports of sanctioned Australian goods fell from May 2020 (sanctions start) to June 2021, Chinese imports of those same goods from the U.S. rose. Particularly noticeable are the increases in China’s imports of U.S. meat products, coal, and cereal grains.

These data demonstrate Beijing’s political savvy in recognizing an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone: concede (to a limited extent) to U.S. pressure by diverting trade from a vocal U.S. ally in order to placate a nationalistic domestic audience. In a similar episode, China resumed purchase of U.S. soybeans in June 2019 (halted during the U.S.-China trade war) after banning Canadian soybeans earlier that spring in retaliation for the arrest of Meng Wanzhou. The move was hailed as a “goodwill gesture” ahead of a meeting between Xi Jinping and Donald Trump, but likely also reflects the use of trade diversion to punish U.S. allies.

The Perils of Managed Trade with China

China’s use of trade diversion against Australia complicates the Biden administration’s professed unwillingness to “improve relations in a bilateral and separate context at the same time that a close and dear ally is being subjected to a form of economic coercion.” As Chad Bown has warned, “the real problem with managed trade is that it may divert, rather than expand, international commerce.”

The Phase One Agreement’ high quotas incentivize Beijing to shift purchases away from other foreign suppliers and toward the United States to overcome anticipated shortfalls. This was true before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted global supply and demand, and it is especially true in its aftermath. However, diverting trade also carries costs. To combat recent coal shortages, China began importing Australian coal last month, which had sat idle in customs warehouses since the ban on Australian coal last December. In 2021, China has also resumed limited imports of Australian copper and cotton, albeit on a much smaller scale than before they were banned in November 2020. These reversals suggest that the diversion of trade away from Australia has not been without costs for China and reveal a willingness to remove restrictions on an ad hoc basis, at least in the short term. Nevertheless, other U.S. allies such as Japan, South Korea, and the EU could be targeted with Chinese trade diversion if the Washington pressures Beijing to renew purchase agreements in ongoing negotiations.

In assessing the Phase One Trade Deal with China the Biden administration therefore has a choice between adopting the Trump administration’s focus on short-term outcomes (such as Chinese purchases for U.S. agricultural and energy products) and pushing for structural reforms in China that will also benefit its allies. The Biden administration has consistently emphasized its willingness to work with democratic allies to confront China. But, this cooperation has largely been weighted towards security policy, not economics and trade. Security cooperation initiatives like AUKUS are low-hanging fruit because the U.S. does not have to compromise its political priorities and its defense contractors to gain a lucrative contract. True economic coordination involves not just telling U.S. allies to say no to China, as the U.S. did during its campaign against Huawei, but also compromising on some U.S. domestic priorities in order to achieve greater leverage vis-à-vis China.

Jiakun Jack Zhang, Wilson China Fellow and Director of the KU Trade War Lab, is on Twitter @HanFeiTzu.

Jackson Martin, Senior majoring in Economics and Chinese at KU, is on Twitter @JMartKS.

Follow the Asia Program on Twitter @AsiaProgram. or join us on Facebook.

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2020, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

Authors

Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Kansas and Director of the Kansas University Trade War Lab

Indo-Pacific Program

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more