Norway’s Supposed Arctic Seafloor Treasures: What Does the Data Show?

Media coverage and an oft-cited resource assessment may be overhyping the Norwegian Continental Shelf’s mineral wealth.

A blog of the Polar Institute

Media coverage and an oft-cited resource assessment may be overhyping the Norwegian Continental Shelf’s mineral wealth.

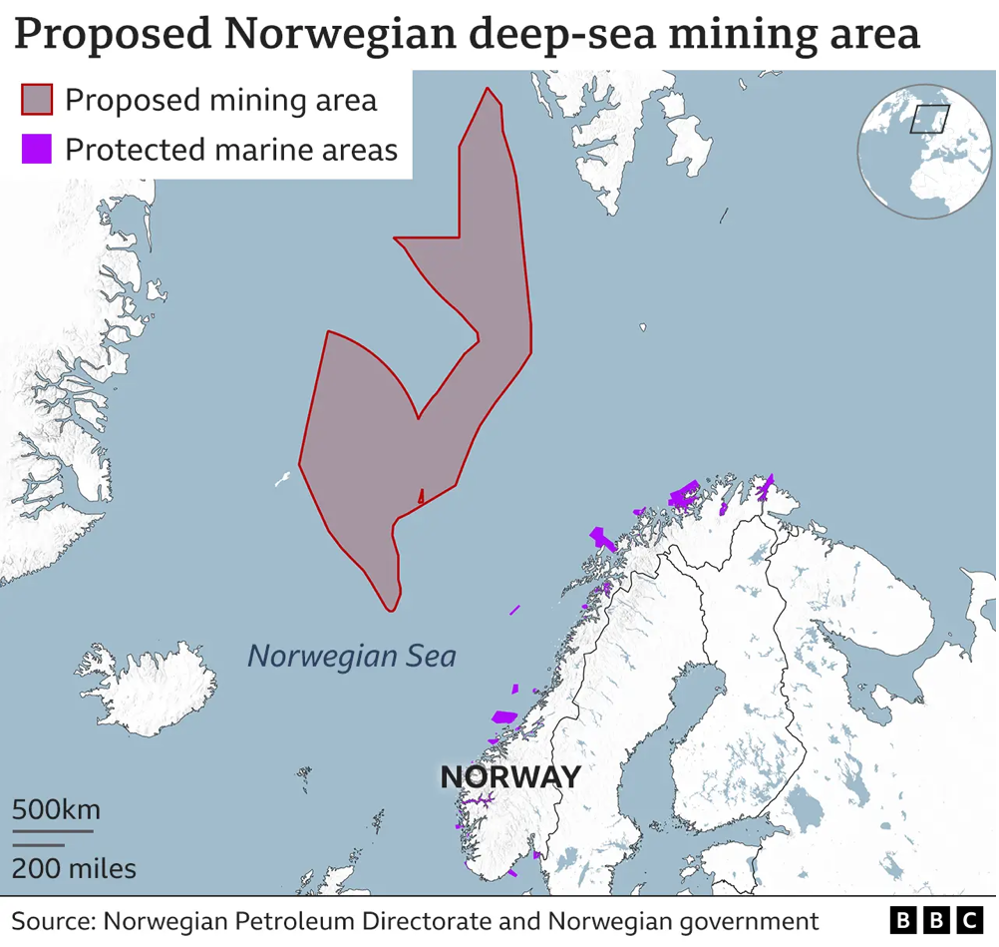

The deadline for public comment has just passed on Norway’s decision to permit seabed mineral exploration in a swathe of its Exclusive Economic Zone, but the move continues to spark controversy, along with significant media coverage. The Norwegian government plans to divide a section of the permitted seabed (comprising about 38 percent of the total 108,000-square mile area designated for exploration) into blocks for auction in the spring of 2025. Reactions from environmental non-profits and other NGOs have been fierce, and even the Council of the European Union has “noted with concern” the development.

The Norwegian government, for its part, pitches the decision in the context of Norway’s history of responsible resources development and extraction, and asserts that the Norwegian Continental Shelf contains “metals and minerals that are crucial for the technology that surrounds us today – such as batteries, wind turbines, PCs and mobile phones,” according to the Norwegian Offshore Directorate’s website (formerly the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate). A January 2023 Directorate assessment of the region claims that the “resources in place are significant. For several of the metals, the mineral resources compare to many years of global production.” Media outlets have seized on this narrative, expounding on the “huge trove of metals, minerals, and rare earths” that the NOD has supposedly discovered and speculating that Norway could “help to break Russia and China’s rare earths stronghold”.

Similar debates continue to rage across the Arctic and worldwide about the extraction of critical minerals, from the Ambler district in Alaska, where the Bureau of Land Management rejected permits to build a road that would enable mining of copper, zinc, and other energy transition metals in the region, to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone in the Pacific, which has become the locus of much of the support and opposition to deep-sea mining. The myriad environmental, governance, social, and other tradeoffs of deep-sea mining versus other forms and types of mineral extraction are beyond the scope of this article. Its purpose is instead to address whether the delineated seabed area is actually likely to contain economically viable concentrations of minerals. (Of course, this is what the Norwegian government itself is hoping to ascertain by auctioning off sections of the seabed to exploration companies.)

The NOD’s resource assessment of the mineral endowment of the Norwegian Continental Shelf did indeed estimate that the NCS contained vast aggregate amounts of metals and minerals; one million tonnes of cobalt, for instance, versus 2023 world cobalt production of roughly 200,000 tonnes. The NOD’s assessment, however, was remarkably light on details, and declined to discuss the most important variable in mineral exploration and extraction: grade. Without data on whether the projected metal endowment of the NCS is sufficiently concentrated to justify the cost of extraction and processing, sheer values of contained metal are practically meaningless. This is especially true of the NPDs’s estimates of lanthanide-series “rare earth” elements, which are relatively abundant in the earth’s crust but are rarely found in economically viable concentrations with mineralization amenable to processing. Others, including the Norwegian Geological Survey, have also critiqued both the NPD’s methodology and choice to release their data in this way.

The actual datasets of the NOD’s exploration voyages, available in English here, tell a different story. The samples of sulphide mineralization collected by NOD teams on the Mohn Ridge, one of the most promising sections of the Norwegian Continental Shelf for mineral deposits because of the presence of “black smoker” volcanic vents, include miniscule amounts (a few parts per million) of the vast majority of metals analyzed, including rare earths, with economically interesting concentrations of copper, zinc, and not much else. Even for copper and zinc, the grades are nothing to write home about; out of sixty samples reported from the 2020 survey of the “Mohns Treasure” deposit, the average copper grade was 0.92%, while the median was just 0.48% (at current copper prices, this equates to an in-situ copper value of roughly $40 to $80 per tonne. Is that worth transporting hundreds of meters to surface in the Greenland Sea?) The fact that the samples are all of sulphide mineralization is also important, since it means that by definition, the analyses only looked at chunks of the seabed that were known to be mineralized, rather than a truly random sampling.

Moreover, the NOD’s own assumptions of the size of Mohns Treasure indicate that it would be a very small deposit, likely not even worth mining if on land – the equivalent of a penny jar rather than a “treasure”. The hope is presumably that the NCS is dotted with richer, as yet undiscovered deposits, all of which could be mined concurrently. Yet a separate Norwegian Institute of Science and Technology voyage in 2015 at another high-priority site along the Mohn Ridge, Loki’s Castle, yielded similar results: “the majority of the samples which display visible sulphide mineralization typically contain 0.5wt% Cu and 1wt% Zn” (again, selection bias is at hand as only the mineralized samples are reported, not the barren ones). Despite decades of academic and government study, no world-class deposits have yet been found – and yet the NOD assessment assumes the existence of many.

Joanna Ponicka of Equivest, a Norwegian/Andorran-based mining exploration and investment firm, also doubts the prospects for success of NCS seabed mining in an excellent Twitter/X thread, in which she writes that she is “struggling to find basis for scientific or economic decision” on the part of the Norwegian government. Ponicka further observes that land-based mineral exploration companies with deposits of comparable size and grade to those on the Norwegian seafloor are typically valued at just US $5 to $10 million. Given the substantial up-front capital expenditure required to initiate a seafloor mining operation, and the inherent challenges of operating in hundreds or thousands of meters of water (to say nothing of the particular climactic, navigational, and other hurdles of Arctic maritime operations), it is hard to believe that any Norwegian seafloor mining operation would be profitable based on the information currently available.

The economics of deep-sea mining overall are far from certain, even in areas like the Clarion-Clipperton Zone where major seabed resources have been more thoroughly explored and understood. Norway appears to be forging ahead with its exploration permitting decision and seafloor auctions in the spirit of wishful thinking – what if a lucky private company does find a “treasure trove”? But it is unlikely that any known deposits on the Norwegian seabed are economically viable, a fact which should let environmentalists rest a little easier and give would-be explorers pause.

Since its inception in 2017, the Polar Institute has become a premier forum for discussion and policy analysis of Arctic and Antarctic issues, and is known in Washington, DC and elsewhere as the Arctic Public Square. The Institute holistically studies the central policy issues facing these regions—with an emphasis on Arctic governance, climate change, economic development, scientific research, security, and Indigenous communities—and communicates trusted analysis to policymakers and other stakeholders. Read more