A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

It’s a dramatic scene: Japanese police armed with rifles chase two young Korean men down the street in colonial-era Seoul. They finally catch them, killing them execution-style. The men’s crime: making a Korean language dictionary, then considered an illegal act of defiance by the Japanese government, which had banned Koreans from using their native language.

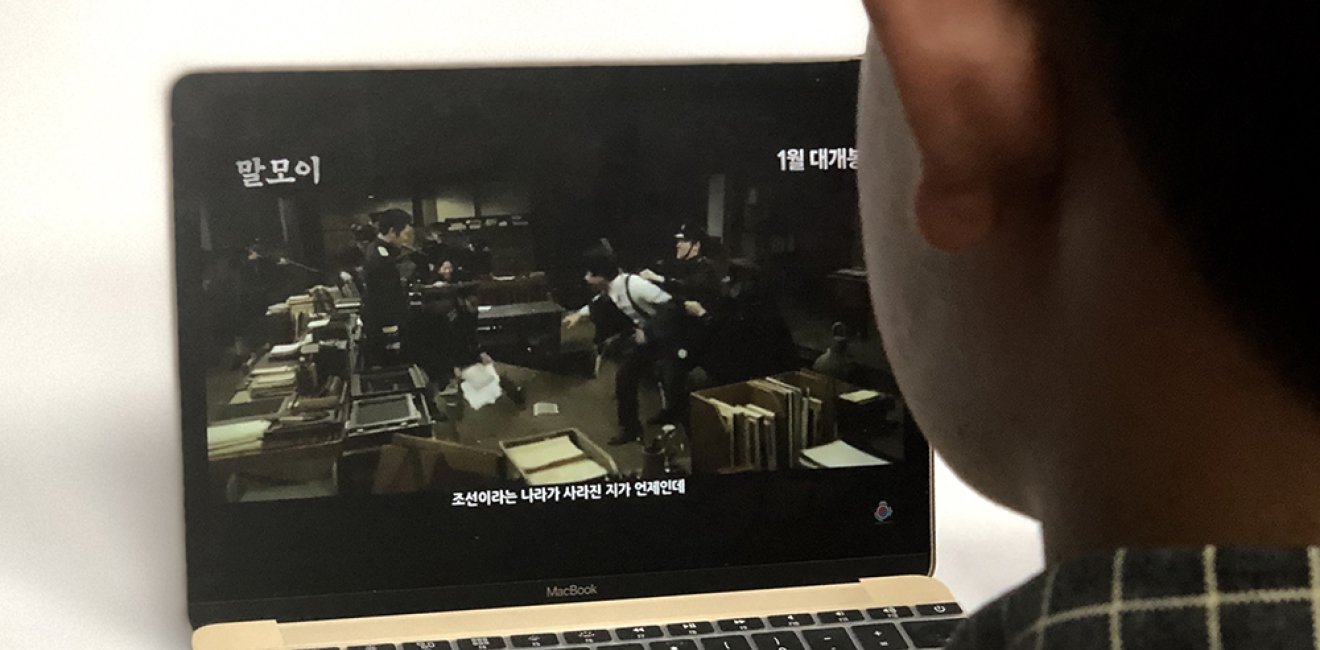

This is a scene from Secret Mission (말모이), a 2019 South Korean movie that I recently watched on a flight from Seoul. The film highlights Korean scholars’ endeavors to publish a Korean dictionary during the period of colonial rule by Japan from 1910 to 1945. Despite the deadly crackdown, the Koreans refuse to give up drafts of the dictionary. The materials become the first Korean dictionary after the country gains independence from Japan in 1945. Today, South Korea celebrates its language, hangeul, every Oct. 9.

Frankly, I do not consider myself someone with a strong sense of nationalism or anti-Japan sentiment. I was born in South Korea a half-century after the colonial period ended. I enjoy eating Japanese food and watching Japanese animation and TV.

I wondered whether films like Secret Mission were meant to highlight our country’s painful history with Japan.

But watching this scene, I felt a surge of emotion and anger that surprised me. I wondered whether recent tensions between Japan and South Korea were affecting my feelings toward Japan. I wondered whether films like Secret Mission were meant to highlight our country’s painful history with Japan.

South Korea is in the middle of a trade dispute with Japan that has brought relations to a low point. In July, Japan removed South Korea from its “whitelist” of trusted trading partners. This decision prompted a boycott and protests in South Korea. Seoul then terminated a military intelligence-sharing deal with Japan, and in September, South Korea removed Japan from its trade whitelist.

The Japanese government claims that South Korea’s lax export system for sensitive strategic material is the reason behind its export restrictions, while Seoul believes the move was retaliation for its top court’s rulings that ordered Japanese firms to compensate Koreans forced into labor during Japan’s 1940-45 colonial rule of the country.

Ordinary South Koreans also got involved. In a July poll, 67 percent of South Koreans interviewed said they were willing to participate in a boycott of Japanese products. The percentage of those with a positive view of Japan dropped to 12 percent from 32 percent in a June poll taken just before the trade spat.

In South Korea, it is typical for movies with an anti-Japanese theme to be released every year, especially targeting commemorative national anniversaries such as March 1, which marks a massive independence march held in 1919, or Liberation Day on Aug. 15th. Not only are the movies entertaining, but they also serve as a reminder to South Koreans of the activists who traded their lives for the country and its people.

Could these movies help us understand the emotions and motives behind the ongoing tensions?

It’s important to remember that Korea and Japan tensions date back centuries, including a seven-year war in the 1500s during Korea’s Joseon Dynasty rule. After the war ended, they established a peaceful relationship. When Japan opened its border and began allowing Western influence in the late 19thth century, however, they faced resistance from conservative elites. As a solution, they shifted their eyes outside and decided to expand Japan’s territory by colonizing less industrialized countries in Asia. They beefed up their influence over Korea through treaties such as the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1876 and the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1905.

Japan officially annexed Korea in 1910. The Korean royal family became Japanese aristocrats. In trying to merge two different cultures and to justify its colonization of Korea without provoking too much Korean nationalism, the Japanese governors implemented its assimilationist policies gradually at first. In the 1910s, they deployed Kenpeitai, the Japanese military police, to forcefully rule the area. After the uprising on March 1, 1919, Japan authorities changed their tactics, instead persuading Korean scholars and writers to encourage fellow Koreans to embrace colonial rule.

After Japan joined World War II, officials turned back to authoritarian policies in Korea, using the country as a source of rice, cotton and labor. Korean men were used for labor as well as for medical experiments and suicide squads, and women for sexual services; they were known as “comfort women.” With Japan’s surrender following the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima during World War II, the colonial period came to an end on Aug. 15, 1945.

Photo: Wikimedia.

Since then, Japan has held the official stance that its colonial rule was legal, and maintains that individual claims against Japanese colonial rule were settled with the 1965 Treaty of Basic Relations between the two countries.

South Korea disagrees, and its Supreme Court ruled last year that a Japanese company must pay four South Korean for forced labor during colonial rule.

The tensions go beyond law and trade. There is a Korean expression, “close but far neighbor” (가깝고도 먼 나라), that refers to Japan. The two countries share many similarities but tensions over their history persist. This animosity has spread into sports and culture. For example, the most heated sporting rivalry is any South Korea-Japan soccer match. You can be forgiven for losing in the FIFA World Cup, but not for being defeated by Japan even in a friendly match.

Secret Mission is based on historical events in the 1940s when teaching Korean was banned by the imperial government. Kim Pan-soo, the main character, is illiterate. He runs into Ryu Jung-hwan, a passionate leader of the Korean Language Society, on the street. They don’t get along at first but grow to like one another, and Ryu begins teaching Kim how to read and write in Korean. Kim joins the project to publish a Korean dictionary.

The movie was highly rated by critics and the South Korean public. But it is not completely free from criticism that it was used to generate anti-Japan sentiment by exaggerating Japanese officers’ violence.

Living in globalized South Korea, I grew up with Japanese pop culture and Japanese products, and even traveled twice to Tokyo. For my generation, anger toward Japan is diluted as historical events are getting away from the present. However, that scene in Secret Mission was powerful enough to move South Korean audiences, even the younger generation of Koreans who’ve never experienced the dark times of colonial rule, including me.

...the pain of the colonial period has never been resolved.

While Secret Mission is just a movie, it reminded me of two things: that the pain of the colonial period has never been resolved, and that the historic tensions have a way of affecting diplomacy and trade today.

While officials typically refer to “future-oriented relationship” in their diplomatic rhetoric, both governments speak in the past tense more often rather than in future tense.

These divided perspectives put fetters upon building a sound relationship between the two countries. South Korea and Japan should move forward to get the historical truths right. And I believe it is the younger generation that could help the two countries eventually leave these powerful sentiments behind -- and change the direction of the two countries’ relationship.

Jihoon Lim is an intern with the Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy at the Woodrow Wilson Center. He studied political science and international relations at Kyung Hee University in Seoul, South Korea.

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2019, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

Author

Indo-Pacific Program

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more

Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy

The Center for Korean History and Public Policy was established in 2015 with the generous support of the Hyundai Motor Company and the Korea Foundation to provide a coherent, long-term platform for improving historical understanding of Korea and informing the public policy debate on the Korean peninsula in the United States and beyond. Read more