A blog of the Brazil Institute

On May 13, 1888, Brazilian Princess Isabel of Bragança signed Imperial Law number 3,353. Although it contained just 18 words, it is one of the most important pieces of legislation in Brazilian history. Called the “Golden Law,” it abolished slavery in all its forms.

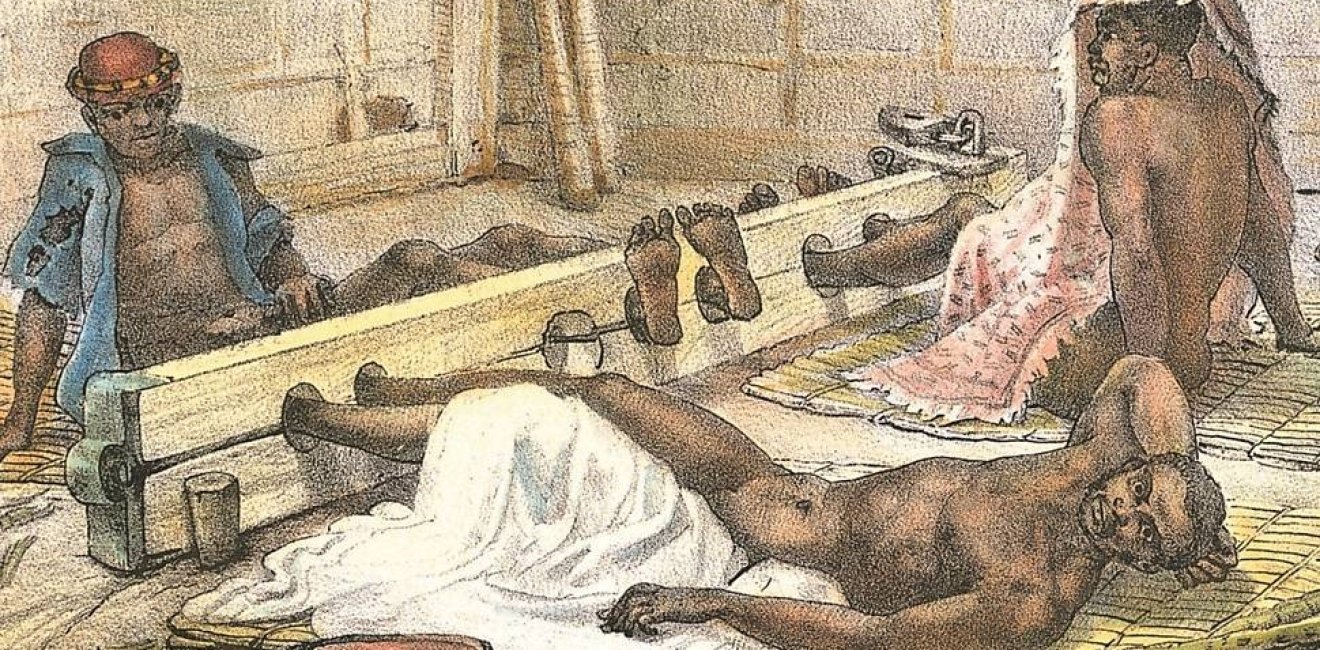

For 350 years, slavery was the heart of the Brazilian economy. According to historian Emilia Viotti da Costa, 40 percent of the 10 million enslaved African brought to the New World ended up in Brazil. Enslaved persons were so pivotal to the economy that Ina von Binzer, a German educator who lived in Brazil in the late 1800s, wrote: “In this country, the Blacks occupy the main role. They are responsible for all the labor and produce all the wealth in this land. The white Brazilian just doesn’t work.”

By 1888, abolition had the support of most Brazilians—including several conservative sectors—the culmination of a long process of societal and economic changes. By the time slavery was abolished, the practice had already begun to decrease due to the modernization of agriculture and increasing migration towards Brazil’s cities from rural areas.

Yet the shift took nearly 70 years. Great Britain outlawed slavery in 1807, and subsequently began to pressure other nations to follow suit—including Brazil upon its independence from Portugal. However, in 1822, 1.5 million of 3.5 million people in Brazil were enslaved and the practice was not simply tolerated, but strongly supported by all segments of society, including the Catholic Church.

Yet in the years that followed, Great Britain ramped up efforts to outlaw the slave trade, seizing slave ships in the Atlantic Ocean, and even attacking a few ports in Brazil. As a result, the Brazilian government passed a law declaring that all enslaved persons were free upon reaching Brazilian soil, though the government did not enforce the law.

As British ships made life harder for slave traders, the supply of slave labor declined and enslaved persons became more expensive. Initially this forced owners to improve living and working conditions, as they could no longer afford the high mortality rates that previously characterized the practice of slavery in Brazil.

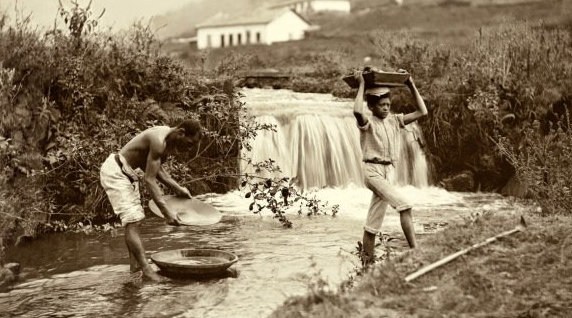

Landowners became increasingly aware that slave labor was making less and less economic sense. Paying low salaries to free men was in fact cheaper than maintaining slaves, for whom the owners were responsible. Thus, the Brazilian government began implementing policies aimed at gradually reducing slavery, although it moved slowly to avoid disturbing owners’ economic interests.

The Gradual Abolition

In 1871, the Brazilian Parliament passed the so-called “Free Womb Law,” declaring that all children born to enslaved women would be free. However, children had to work for their parents’ owners until they were adults in order to “compensate” the owners. At the time, many notaries–with the knowledge of local parishes–forged birth certificates to prove that child slaves were born before the law had been passed. According to Joaquim Nabuco, a lawyer and abolitionist leader, thanks to this piece of legislation alone, slavery would remain in effect in Brazil until the 1930s.

In 1884, a new law came into effect that freed enslaved persons who were 60 years of age or older. More perverse than the latter, this law gave owners the power to abandon enslaved persons once they had become less productive and more susceptible to diseases. Moreover, it was rare that an enslaved person even made it to his or her 60th birthday.

The Catholic Church ended its support of slavery by 1887, and not long after the Portuguese Crown began to position itself against it. On May 13, 1888, the remaining 700,000 enslaved persons in Brazil were freed.

Post-abolition Brazil

The legal end of slavery in Brazil did little to change the lives of many Afro-Brazilians. Brazil’s abolitionist movement was timid and removed, in part because it was an urban movement at a time when most slaves worked on rural properties. Yet the abolitionst movement was also more concerned with freeing the white population from what had come to be viewed as the burden of slavery. Abolitionist leaders were unconcerned with the aftermath of abolition. There were no policies to promote integration, or plans to help former enslaved persons become full citizens through providing access to education, land, or employment.

Indeed, Brazilian elites largely opposed to the idea that Brazil would have a majority Afro-Brazilian citizenry. After slavery was formally abolished as a legal institution, the government implemented a policy of branqueamento, or “whitening”—a state-sponsored attempt to “improve the bloodline” through immigration: Brazil was to accept only white Europeans or Asian immigrants. Meanwhile, with nowhere to go and no other way to earn a living, many freed slaves entered into informal agreements with their former owners. These amounted to food and shelter in exchange for free labor, thereby maintaining the status quo.

Today, vestiges of the slave system can still be witnessed in Brazilian society. It is not a coincidence that only 53 percent of the Brazilian population identify as Afro-Brazilian or mixed, but make up two-thirds of incarcerated individuals and 76 percent of the poorest segment of the population. More than any other nation in the Americas, Brazil was profoundly shaped by slavery—a legacy that the country still struggles to address more than 350 years after the first enslaved African landed on its shores.

Like the content? Subscribe to the Brazilian Report using the discount code BI-TBR20 to get 20 percent off any annual plan.

Author

Brazil Institute

The Brazil Institute—the only country-specific policy institution focused on Brazil in Washington—aims to deepen understanding of Brazil’s complex landscape and strengthen relations between Brazilian and US institutions across all sectors. Read more

Explore More in Brazil Builds

Browse Brazil Builds

They're Still Here: Brazil's unfinished reckoning with military impunity