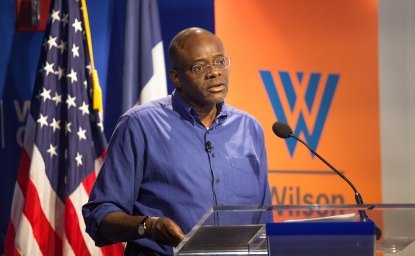

The American government's new special adviser on the Great Lakes region, Howard Wolpe, comes to the post with the best part of three decades' experience in the Africa policies of U.S. administrations behind him. In the second of a two-part interview with AllAfrica, he discusses how the Obama administration could improve its diplomacy and strengthen peace-building in Central Africa.

Wolpe chaired the Subcommittee on Africa of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives for 10 years, later served as President Bill Clinton's special envoy to the Great Lakes region and went on to become director of the Africa Program and Leadership Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, DC. He was interviewed at the beginning of his first trip to Southern and Central Africa since he took up his current appointment. (Read Part I of the interview.)

In testimony earlier this year to the Senate Subcommittee on Africa, referring to when you were the Great Lakes envoy for the Clinton administration, you said [in relation to the Central Intelligence Agency] that you were "struck by how often we were flying blind – with little solid information about the various military elements involved in the conflict, or about the role of ethnic diaspora that were financing and fueling many of the conflicts." Has this improved? Are you doing something about it?

I think there are still some very major gaps in our knowledge and I don't think that there have been adequate resources committed to that process, particularly working with the diaspora. I think that's a terrible mistake and makes much more difficult what we are trying to do, and I am continuing to make that case in Washington.

You talked about a woeful paucity of African language skills in the U.S. government – a lot of publicity was given when General [Scott] Gration was appointed [as special envoy to Sudan], because he speaks Swahili, and it was not quite evident what Swahili had to do with

Sudan

Is something happening in that area?

There's an awareness of that, and I think that the [State] Department now is beginning to expand considerably its efforts at broadening language instruction. But it takes time to overcome the deficit, and the deficit remains and it's a very significant deficit.

You also said in your testimony that the U.S. needs "instruments and processes that are less focused on imposing Western institutional structures than in assisting nationals in divided societies develop a recognition of their interdependence and of the value of collaboration even with former enemies." Can you flesh that out?

When I left government [after the Clinton administration] and moved over to the Wilson Center, the World Bank brought me on as a consultant to think with the bank about post-conflict strategies in the Great Lakes region.

I expressed to the bank my frustrations as a diplomat with conventional approaches to peace building. We put a lot of pressure on leaders to sign agreements but that doesn't mean the next day they suddenly see the world any differently than the day before. And then we have this kind of template – a checklist if you will – of things to do to stabilize the situation: you stand up an independent electoral commission, you provide support for multiple parties, you stand up independent judicial institutions and so on. But never in this array of activities do we talk about working with leaders directly – their mindsets, their perceptions, their mistrusts, their fears.

Moreover, the other thing we do is that we focus almost exclusively on one tiny dimension of democracies – elections. Elections are important; they are a way of establishing a legitimate government. But what we forget is that underlying every stable Western democracy is a set of underlying agreements about who constitutes the nation, about recognition of the interdependence of the various elements of the nation, recognition that politics does not have to be a zero-sum, "winner-take-all" proposition, there is a basic set of understandings about the rules of the game, how power is organized and how it should be shared, there are certain trust levels that exist among key leaders, even among opposing leaders.

The reality is that in most divided societies, none of those agreements are in place. The problem of building democracy is not a shortage of democrats in these societies. I don't know anywhere where people enjoy being tortured or having their rights violated. That's not the point. The problem is that people in these societies don't always see themselves as part of the same political system and they feel threatened by people different than they, outside of their own universe.

What I would argue is that in these societies people know how to compete. It's how to collaborate that is the principal challenge. So when I talk about new processes and strategies, I am focused upon the need to build collaborative capacity, to build cohesion, to alter the conflict paradigm, which is a "winner-takes-all," zero-sum game, to build trust, to build relationships, to give people communications and negotiating skills so that they are better able to put themselves in the shoes of the other and fashion solutions that will satisfy the interests of all.

So that's what I proposed to the World Bank, that we needed a different kind of program that would work directly with leaders. We used Burundi as our initial experiment. We spent several months interviewing the heads of various organizations and institutions and got a buy-in from everyone – from the most extreme Tutsis, the most extreme Hutu, church leadership, grassroots women leaders, politicians, military leaders, rebel leaders, and we launched this training program.

We were targeting initially 100 people

It was stunningly successful. In six months' time, we had built so much cohesion among the 65 leaders we were then working with that the Tutsi chief of staff of the army and the six Hutu rebel groups that were participating, asked if we would organize training for their military commanders to prepare for the ceasefire that had not yet been signed. So we brought 37 military commanders into Nairobi in November of 2003 from the battlefield into this workshop. And again at the end of the week they had become so cohesive that they asked that we expand this effort as rapidly as we could.

So this program is still ongoing in Burundi six years later now, and at the request of the Burundians, 100 members of the high command of the army were trained, 100 members of the high command of the police, the council of ministers of the new government. All the political parties were brought into this kind of process before the election, to give them a sense of ownership of the election. It's been a really remarkably exciting development.

If you go to Burundi today, though they still have many issues in front of them, you will no longer hear the dialogue framed in terms of Tutsi versus Hutu. And despite the political confusion, the cohesion of both the army and the police high commands has remained intact.

Can the same be done in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)?

We were invited because of the success of that Burundi program, by the diplomats resident in Kinshasa, to come into Kinshasa about eight months before their [2006] election when they suddenly realized that there had been no political preparation for the election. They had invested almost U.S. $430 million in the logistics of the election but with no political preparation.

They were very skeptical that Congolese leaders would be receptive to the Burundi type of strategy but they were so desperate they asked if we would make the rounds, and much to their surprise we got a buy-in from everyone, from [Etienne] Tshisekedi and [Jean-Pierre] Bemba to [Joseph] Kabila's people, church leadership, everyone

Could it work in eastern DRC now?

The Wilson Center is working in the east now; I'm not there now but the program continues in the east

We've done training with Mai Mai and Tutsi militias together, we've done training for the 8th and the 10th military regions of the FARDC (Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo, the government army), we did training before the election with leaders of all the belligerent communities, first in North Kivu and then in South Kivu. That work was so successful that there was not one instance of political violence prior to the election in either North or South Kivu. Violence erupted again afterwards when there were these wars involving [rebel leader Laurent] Nkunda and the government and so on.

So we think that this has had impact, although Congo has 60 million people and Burundi has eight million, so critical mass is going to take a much longer time to achieve in a place as large as the DRC.

What is the role of American companies in the mineral industry in the East? Is that part of the problem?

I can't be very specific about which companies operate in the east. There are American interests in Katanga – copper and other interests – but I think it's fair to say that all multinationals need to be sensitized about the implications of purchasing conflict resources, much like conflict diamonds.

In the case of some of these products, like tannerite or coltan, it is not easy to differentiate where they come from and to disaggregate them when they get overseas. But there are things that can be done locally to begin to monitor both mineral and dollar flows, at the point of origin, right at the mines themselves, that requires building Congolese administrative capacity to do that.

I think that we all are interested in pushing for a multi-faceted program that would both try to deal with end-users – but that will take a long time to achieve – and more immediately to try to figure out ways of getting control of resources and the monetary flows at the source of the activity.

So that's on the administration's agenda?

Yes.

From the perspective of somebody who served as chair of the House Africa Subcommittee, from your experience as a Clinton envoy and that in Burundi, are you more or less hopeful now than in the past about peace in the Great Lakes region?

I am more hopeful. Keep in mind that the last time I was on this job, we had two wars that were in full steam and I was constantly doing shuttle diplomacy in both Congo and Burundi. It was just horrendous.

Now at least we have a more localized focus of concern, which is the eastern Congo. Burundi has made good progress. They have an election coming up in 2010 and there's a lot of anxiety surrounding that; people want to be certain that all the guns in the population don't get activated in militia activity. But I'm very optimistic about the direction of change in Burundi.

The Congo has a much longer ways to go but I am very excited to see the level of engagement now by the international community more broadly, which has not existed for the last several years. For many years we were giving very mixed messages to the government in Kinshasa.

What were the mixed messages?

There were times at which the government was either being encouraged in, or discouraged from, pursuing a military solution in the east against Nkunda. Three military humiliations were suffered as a result by the Kinshasa government. There just wasn't any continuous diplomacy.

Another example – there was this very significant achievement in January of last year, of the so-called Goma Accord, that involved a number of key players in the Congo

It was a remarkable achievement to get all these groups coming together and signing this peace accord, and the international community was very engaged in supporting that effort. But immediately after the signing of the agreement, everyone left the field. All the diplomats from overseas returned, all of the Congolese leaders who were involved in the process went on to other things, were no longer involved in Goma, and there was no follow-through.

So the implementation of the Goma Accord died. Every time you go the mountain-top and you don't achieve your goal, it becomes harder and harder next time to go to the mountain-top, and people were so disillusioned by this whole process. Had we had the kind of sustained diplomacy and engagement that we now, I think, are capable of doing because of this new engagement of envoys, and the new partnership of varied parties— I think we can maintain the process much more effectively.