As the global economy becomes increasingly interconnected, so too have the risks. A single disaster or event in one region can have severe implications felt halfway around the globe. No single risk illustrates this interconnectedness better than climate change. The increased frequency of extreme weather events and their growing intensity is affecting every facet of the world and humanity. Extreme weather events have created added strain on global food production, caused supply chain disruptions, and are constantly testing the endurance of global infrastructure as well as financial resiliency. Addressing climate change is a complex and daunting task that requires an international coordinated response from policymakers. To enact effective change, however, policymakers must do more than simply implement policies in a unilateral fashion; they must formulate public-private partnerships that can execute such actions. One key player that can help facilitate this, and has yet to be fully utilized, is the insurance industry.

The insurance industry is uniquely positioned to drive a fundamental improvement of sustainability practices across the global economy through its vast financial assets, expertise, and influence. It touches virtually every sphere of human endeavor, and insurers’ ability to effectively grant or revoke permission for companies to operate affords them singular leverage in relation to curbing high-risk behaviors and encouraging financial resiliency. In 2019, 820 natural disasters around the globe caused overall losses of US$150 billion, of which only US$52 billion were insured. This widening protection gap, and the indiscriminate nature with which extreme weather events occur, could lead to a dramatic rise in global poverty levels unless addressed. Creating more access to insurance solutions can expedite recovery efforts to restore livelihoods and rebuild critical infrastructure so that people, communities, and economies can rebound.

Traditionally, policymakers have addressed climate change via regulatory means, like carbon taxes, cap-and-trade programs, and stricter emissions standards. From an insurance perspective, policymakers have worked with insurers in the promotion of premium rate relief for companies who practice responsible behavior, like utilizing eco-friendly manufacturing processes. This approach has proven effective and will be part of the solution to combat climate change for the foreseeable future. The next evolution in the utilization of insurance to combat climate change involves policies that encourage companies and insurers to participate in innovative insurance solutions. Future-proofing food supplies, rethinking insurance’s role in energy and infrastructure, and designing resilient infrastructure solutions that are affordable for multiple stakeholders are three key areas of innovation that policymakers should pursue alongside the insurance industry.

Future-proofing Food Supplies

Policymakers understand that a critical aspect of climate change is its impact on global food supplies and agriculture. Climate change has undercut the reliability of the years of data and weather patterns farmers have traditionally depended on to plant and harvest their crops. Extreme weather events, dramatic fluctuations in precipitation, and heat patterns are having a detrimental impact on crop growth, livestock health, fisheries, and other related resources. The United Nations’ International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is forecasting a 2 to 6 percent decrease in global crop production every decade for the foreseeable future. While policymakers have implemented various types of crop insurance initiatives designed to help abate some of these risks for farmers, these programs utilize an outdated, retroactive risk modeling that does not contemplate climate change impacts, and provides funds for losses only once they have occurred. Such programs do nothing to meet the dynamic nature of climate risks, nor do they help smaller, less financially stable farmers salvage their crops and livestock in real time.

When losses can be anticipated, such as during extended droughts, existing parametric insurance programs play a pivotal role for farming communities. Parametric insurance policies utilize pre-determined triggers to determine whether a loss is likely to occur, such as insufficient rainfall. This allows insurers to pay insurance claims proactively and allows farmers to replant crops within the same harvest. Some smaller innovative companies, like AcreFrica, are deploying these types of solutions in Kenya. By embedding a mobile-activated code in the bags of seeds, farmers obtain immediate drought insurance. If insufficient rainfall occurs, measured via satellites and sensors, funds are sent automatically to farmers. While countries like the United States have made crop insurance programs available and affordable to farmers, often via premium subsidies and tax incentives, this is not a widely utilized concept. Emerging countries do not have these types of advanced insurance programs in place that would provide farmers access to risk transfer products, like crop insurance. Policymakers in developing economies could work with insurers to provide more proactive and innovative parametric program structures to encourage participation by private insurers in these markets. Parametric policies, especially those leveraging innovative technology and dynamic data modeling like that found in AcreFrica’s solution, help reduce the overall severity of losses over time, create a more resilient food production supply chain, and build the necessary financial resiliency and economic stability for emerging markets.

A select number of countries have leveraged these types of programs to help establish insurance funds. Sovereign parametric insurance programs—where national governments are the buyer and the insurance relies on satellite and data modeling rather than on-the-ground damage assessments to estimate the cost of disasters—help countries manage climate disasters and enable expedited recovery efforts. Surprisingly, developing country governments have been quick to adopt these programs at the national level to offset catastrophic losses. But they have not been successful in encouraging the insurance industry to invest in creating the primary insurance markets (such as business interruption insurance vehicles) so their citizens and businesses can also benefit from these types of financial risk transfer tools.

Building for the New Normal: Impact on Energy and Infrastructure

Working towards cleaner, more efficient energy standards has long been an objective in the fight against climate change. In an interesting twist of fate, the fallout from COVID-19 has aided this task by raising the profile of clean energy projects and increasing their importance for large energy producers. For instance, in the aftermath of the pandemic, the French oil behemoth Total cut capital spending by more than 20 percent and eliminated share buybacks. However, the unit dubbed “new energies,” which included investments in alternative energy infrastructure such as wind and solar, was spared from budget cuts.

The pandemic lockdowns knocked the price of oil from above US$60 a barrel down towards $0, an unprecedented benchmark. Although negative oil prices were an anomaly related to futures contracts, and prices are slowly recovering as lockdowns end and OPEC cuts production until significant demand returns, the future of oil assets remains uncertain. Policymakers had been pressuring oil companies to diversify from these stranded assets to alternative sources well before the pandemic, but the unique slump in oil demand is a rare opportunity to accelerate these efforts.

As cheap oil dominates the headlines, policymakers must work even harder to ensure that clean energy investments like those undertaken by Total continue to proliferate. They can do this by:

- Increasing the number of new commercial and residential real estate developments required to have energy efficient systems installed, such as solar panels.

- Working with insurers to encourage insurance premium rebates to companies and residences that adopt energy efficient infrastructure improvements, such as the installation of solar panels and other alternative energy solutions.

- Working with insurers to expand their investments in renewable and clean energy vehicles via financial incentives (such as tax breaks). Examples of investments include MetLife’s ownership in a solar PV power plant in Texas, and Allianz having investments in wind farms and solar parks throughout Europe.

- Increasing the adoption of Feed-in tariffs, where homeowners are compensated for any unused solar energy that is returned to the power grid.

- Easing restrictions placed on offshore wind farms.

While it is difficult to determine the lasting impacts of the pandemic on global travel, early indicators show some changes may be permanent, with lasting impacts on infrastructure maintenance at critical transportation hubs. As firms around the world have shifted to teleworking policies, travel has declined drastically, with air travel down more than 90 percent from this time last year. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) estimated that demand for air travel in 2021 will be 24 percent less than what it was in 2019, and not return to pre-pandemic levels until 2023. IATA’s most pessimistic recovery scenario projected a 41 percent decrease in demand by 2021, with a five to seven-year timeframe before returning to 2019 levels. This is fueled both by consumer fears and shifting corporate views on “essential business travel” needs, especially with increased video conferencing capabilities.

This reduced travel has helped to curb greenhouse emissions in the short term, but it has also halted key infrastructure improvements at airports and other transportation hubs. To keep infrastructure improvement projects on the agenda post-pandemic, policymakers can work with insurers to establish the types of incentives that encourage energy-efficient improvements to critical infrastructure like airports and ports, such as discounts on insurance premiums.

Policymakers need look no further than California as an example. The insurance commissioner for the state recently introduced the Climate Smart Insurance Products Database, a groundbreaking list of green insurance policies. Individuals and businesses alike can choose from hundreds of insurance policies that address climate risks, such as policies that factor green energy use in the discounting of insurance premiums.

Designing Affordable Resiliency

As the world’s population creeps towards 8.5 billion over the next decade, urbanization and development of megacities around the world is accelerating. This rapid urban development, however, has not fully accounted for the new risks introduced by climate change. The past few years has shown the impact of these new weather patterns—causing devastating floods across the United Kingdom and Indonesia, igniting powerful wildfires throughout Australia and the Amazon rainforest, and bringing record-breaking high temperatures to Siberia. Houston, the fourth largest city in the United States, has now seen three consecutive 1,000-year floods in the past two years. To put this in perspective, 1,000-year floods statistically have a 0.1 percent chance of happening in any given year. These types of floods not only cost billions in damages, but also displace thousands of people. Current city planning and construction has further exacerbated these weather events by limiting natural mitigation systems such as root systems, forestry, and other barriers that reduce flooding.

By working with policymakers, insurers could help guide a more resilient approach to the development of major cities. Policymakers must enact stronger guidelines for building codes, aligning with insurers’ risk models to limit losses. Encouraging developers to consider the new threat landscape that extreme weather events are creating, via measures like reduced insurance premiums, can drastically reduce the overall damage and loss of economic activity.

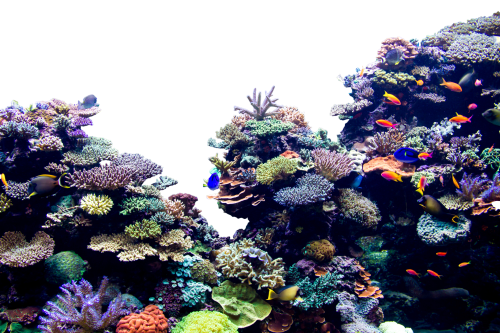

There is a school of thought, now backed by a growing body of evidence, that suggests that protecting nature’s boundaries is critical. This is particularly important in post-disaster reconstruction cases where questions of build back, build back better, or build back at all require consideration of nature’s lines of defense. Barrier reefs, for example, offer clear advantages in abating storm surges and coastal flooding, as do mangroves. Groups like Conservation International are exploring ways to leverage these natural defensive systems to reduce risks of flooding and property damage in collaboration with insurers. Their objective is to not only limit potential damage, but also work to establish greater access to insurance solutions in developing countries. By reducing the risk profile of property projects in developing countries, insurers can expand their risk appetite into regions they might have otherwise deemed too risky. This can be encouraged with the support of policymakers enforcing these types of “natural defense” building codes.

Integrating these natural defenses into man-made projects is not the only way to leverage the protection they provide. In many places around the world, natural assets act as the primary barrier against natural disasters and extreme weather events. Coral reefs, mangroves, wetlands, and forests can often minimize the damage caused by these events near metropolitan areas. It is equally important to protect these natural assets, much like property developments are protected.

The effects of human development and natural degradation (such as wind, rain, and erosion) takes its toll on these natural barriers, rendering them less effective over time. Fortunately, a select number of pioneering insurers have developed highly bespoke products to insure nature’s assets. One of the first, and most notable projects, was an insurance policy designed to protect the Mesoamerican Reef in the Caribbean Sea. By quantifying the economic impact of potential damages and lost GDP that would be incurred should the reef cease to exist, insurers were able to develop an insurance policy protecting this asset. The policy would pay for the maintenance, revitalization, and repair efforts needed if the reef sustained any damage.

While these types of customized insurance solutions are uncommon, it is imperative for policymakers to encourage more of these solutions into their broader strategy for fighting climate change. Working in collaboration with policymakers and the private sector, insurers can help establish added layers of financial resources that will not just maintain natural assets, but also help reduce damages and protect economic interests while building more resilient communities.

This approach allows for both proactive regulatory measures and revitalization efforts to work in unison. Multilateral organizations like the World Bank have also developed and promoted sovereign insurance funds to address these types of complex, large scale risks with insurance funds, working directly with sovereign governments. However, there is greater scope to promote this approach, e.g. by involving the participation of private sector insurers and working closer with policymakers to establish subsidiaries. Doing so would both encourage governments to offset potential losses from their balance sheets and enable private sector participation in these types of innovative risk transfer solutions.

Aligning insurance underwriting requirements and regulations, via policies that allow insurers to influence buying behaviors, further encourages the proliferation of these innovative solutions. The requirement to not only keep natural protective barriers intact as regions become developed, but also mandating the ongoing maintenance of such natural barriers as part of the insurance policy, will have a lasting impact in terms of limiting potential economic losses and damages from extreme weather events.

This is akin to the practices employed by insurers and regulators during periods of urbanization in the late 19th century. When large cities, using wood as the dominant construction material, expanded along with the adoption of electricity, stricter building codes were required as a public safety measure. This served a dual purpose from insurers’ perspective: stricter building codes and fire prevention measures enabled insurers to both reduce damages and contain losses in highly urbanized environments.

Regulation and Public-Private Partnerships

Public-private partnerships are key to supporting initiatives that combat climate change. Last summer, the Bank of England’s Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) stated that it would work with United Kingdom insurers to determine how climate change will affect their finances. Given the impact climate change is having on insurance claims globally, the PRA is wise to investigate how climate change will affect insurers’ balance sheets as it will have a direct impact on the bank’s financial health. California’s insurance regulator has followed a similar posture, asking insurers operating in the state to conduct veritable climate stress tests on their balance sheets to not only identify stranded assets exposed to climate change, but also recalibrate their liabilities.

Policymakers must work with insurers globally to include climate change impacts into insurance underwriting models, compelling more businesses to make climate-sensitive changes to their operations in order to secure favorable premiums or coverage in the first place. Some insurers have taken steps in this direction. The insurance giant Chubb says it will no longer underwrite risks related to the construction and operation of new coal-fired plants. (Exceptions to the policy will be considered until 2022 in regions that do not have practical near-term alternative energy sources and taking into account the insured’s commitment to reduce coal dependence.)

However, while some carriers like Chubb are making strides to limit their carbon footprints and wield their investment dollars to fight climate change, it is not the industry standard. Encouraging more insurance carriers to adopt this mindset and aligning shared interests would not only drive effective climate risk reduction, but also propel insurers to expand the access of their products to more emerging markets, creating broader global resiliency. The Sustainable Insurance Forum (SIF) is one such group that is gaining momentum with this effort. SIF is a global network of insurance regulators working on the sustainability issues confronting the insurance industry, and it is influencing regulation aimed at reducing the impact of climate change.

The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) is an important element of the public-private partnership needed on a global scale. The ICC has launched its Climate Coalition, a global network of over 45 million businesses that convene on a regional level to devise solutions aimed at reducing climate change’s impact—it is a type of marketplace, just as Lloyd’s is the marketplace through which insurance buyers and sellers meet. The word “public-private partnership” is used casually, but the ICC’s Climate Coalition is a global resource where this partnership has the chance to create public-private partnership models that can be scalable globally.

Climate change poses a global threat that requires a multi-faceted, international coalition to help change its trajectory. As governments seek to implement new guidelines and goals for how to fight its impact, they would do well to recognize that insurers can play an important role—through data sharing and financial tools that equip countries with additional funds and resources needed to rebound quickly from disasters linked to climate change. Policymakers must encourage insurers to expand their market access, bringing sophisticated risk transfer solutions to both advanced economies and those throughout the developing world. With an aligned agenda, this type of public-private partnership can affect material change and build greater financial resiliency while navigating the new risk landscape shaped by climate change.

Authors

Environmental Change and Security Program

The Environmental Change and Security Program (ECSP) explores the connections between environmental change, health, and population dynamics and their links to conflict, human insecurity, and foreign policy. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Can Climate-Resilient Agriculture Become an Engine for Syria’s Post-Conflict Recovery?

ECSP Weekly Watch | March 10 – 14

ECSP Weekly Watch | February 17 – 21