In Rwanda today, the government makes no distinction between its two main ethnic groups, Hutus and Tutsis: ethnic identity cards are banned and national unity is promoted. But 10 years ago, the ethnic distinction was evident and turned deadly. From April to July 1994, Hutu extremists slaughtered 800,000 innocent Tutsis and moderate Hutus during a 100-day genocide while the world stood by, inactive and silent.

In Rwanda today, the government makes no distinction between its two main ethnic groups, Hutus and Tutsis: ethnic identity cards are banned and national unity is promoted. But 10 years ago, the ethnic distinction was evident and turned deadly. From April to July 1994, Hutu extremists slaughtered 800,000 innocent Tutsis and moderate Hutus during a 100-day genocide while the world stood by, inactive and silent.

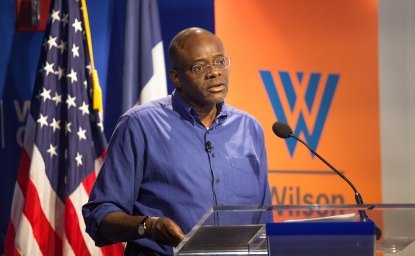

"The world silently watched and chose not to act," said the Wilson Center's Africa Program Director Howard Wolpe, former U.S. special envoy to Africa's Great Lakes region. "Remembering Rwanda seeks not only to remember both the victims and survivors of the genocide, but also to pay tribute to the remarkable courage and vision of Rwandans who are undertaking the painful, difficult work of reconciliation and reconstruction."

For the past three months, the Africa Program has co-hosted events with the United States Institute of Peace, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Council on Foreign Relations, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Refugees International and other groups to commemorate the horrific events of 1994 and generate public conversation on lessons learned from the failure to act and about the international capacity to prevent such atrocities, or to intervene in the event of mass killings.

The Rwandan genocide began on April 6, 1994 when the plane carrying Rwanda's Hutu President Juvenal Habyarimana was shot down. The mass killings, however, were not spontaneous; they were carefully planned over many months. The country's Hutu government had been embroiled in civil war for three years with the Tutsi-led rebels—-the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF)—-when, in 1993, the two sides negotiated a ceasefire and signed the Arusha Accords, which would insure broad power-sharing between Tutsi and Hutu. At this point, the United Nations sent in Canadian General Roméo Dallaire to reinforce the Accords and head the UN peacekeeping forces there.

The Hutu extremists, fearing the Accords would diminish their power, began planning to "exterminate the enemy." They spent several months preparing death lists, importing tens of thousands of machetes, and disseminating anti-Tutsi propaganda. In April 1994, the Presidential Guard, the Rwandan Armed Forces, and Hutu civilian militia-—called the interahamwe—-then executed a genocide, enlisting the help of ordinary citizens to kill their Tutsi neighbors. The genocide ended when the Tutsi-led RPF, headed by Paul Kagame, took over the capital, Kigali. More than a million Hutus, including the genocidaires who spearheaded the killing, fled to neighboring Zaire.

Periodic violence between Hutus and Tutsis dates back to shortly before Rwanda's independence from Belgium in 1962, spurred by ethnic divisions and the favored role given to Tutsis by the Belgian colonial rulers. "Genocide in our country was, in many ways, a culmination of the hatred initiated during the colonial period," said President Kagame at an April 21 Director's Forum at the Wilson Center, "but it was also due to the failure of post-colonial rulers in Rwanda to divorce the legacy of that past."

President Kagame said post-colonial Rwandan governments suffered from an ideology of exclusion that penetrated all aspects of society, segregated ethnic institutions, and a culture of impunity that rewarded criminals. "All these were a recipe for a catastrophe that was waiting to happen," he said. "It is no surprise, therefore, that genocide happened when it did." Yet the international community was silent. "The world had the means and the resources to act, but lacked the will to do so."

An Immobile International Community

In January 1994, General Dallaire learned of the Hutu extermination plot and cabled UN headquarters seeking permission to help thwart the plot by raiding an identified arms cache. But he received strict orders against intervening from Kofi Annan—-then head of the UN peacekeeping office—-who said taking action would violate Dallaire's peacekeeping mandate. When the killing began three months later, about 2,500 UN blue-berets were in Rwanda under Dallaire's command. Belgium soon withdrew its forces after several of its peacekeepers were assassinated. Meanwhile, the United States—-still reeling from the deaths of 18 U.S. soldiers in Somalia a year earlier—-led efforts at the UN Security Council to withdraw or reduce Dallaire's force, despite his pleas before and during the mass killings for more troops. On April 21, the Security Council reduced the force to 270 soldiers.

Reflecting on that time, Dallaire feels enormous guilt about his failed mission. He expressed deep anger at the world's refusal to intervene. In 1994, "Rwanda did not count," he said at an April 22 Wilson Center Director's Forum. He repeatedly asked, "Are all humans human or are some humans more human than others?"

Reflecting on that time, Dallaire feels enormous guilt about his failed mission. He expressed deep anger at the world's refusal to intervene. In 1994, "Rwanda did not count," he said at an April 22 Wilson Center Director's Forum. He repeatedly asked, "Are all humans human or are some humans more human than others?"

No one came to Rwanda's aid when it was clear that genocide was occurring, he said, because the developed world feared casualties of its own. "Our lives are more important than theirs," he said, bitterly. When the developed world refused to authorize UN intervention, he attempted to use the media to "shame the international community" into action by devising a system to get cameras access to the carnage and to disseminate the stories quickly.

Despite a later resolution authorizing an increase in UN troops and an ambiguous intervention in late June by the French (who had long-standing ties with the leaders of the genocide), no more blue-berets arrived before the effective end of the genocide on July 18, when General Kagame declared the war over.

"Can we morally accept our institutions establishing a pecking order of who counts and who doesn't?" Dallaire asked. "Until humanity is the primary motivation and not the ‘national interest,' we'll have difficulties in intervention."

Rebuilding and Reconciling

In the past decade, Rwanda's government has restored schools, hospitals, and basic civil services and ratified a new constitution, while the country has seen modest, steady economic growth. But Kagame's Rwanda remains a traumatized society. While he won the recent presidential election with an overwhelming vote, human rights advocates have criticized restrictions placed on the media and opposition parties. Other serious problems remain. The average life expectancy is only 40 years and an estimated 60 percent of Rwandans live below the poverty line.

Since the genocide, the government adopted a policy of open return and reconciliation for many of the former soldiers who participated in the genocide. In addition, the government has released tens of thousands of Hutus from prison who have moved back to their communities. Rwanda's devastated judicial system simply could not cope with the 150,000 Hutus imprisoned awaiting trials and decided to utilize a traditional system of community-based adjudication, called "gacaca."

"This is the only instance I know of in the world where the killers involved in a genocide have been reintegrated into the communities whose families they destroyed," said Wolpe.

Most of the Hutus who fled the country after the genocide have been reintegrated in their former communities; however, remnants of the Hutu extremists still remain in the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) and pose a continuing threat. Thus President Kagame observed: "Unless there is a concerted effort by the international community to deal with these forces that committed genocide and continue to harbor the idea of further genocide, they remain a potential threat to peace and security—-not only to Rwanda, but to the whole region."