The Soviet Committee for State Security (KGB) had its own educational system, at the pinnacle of which was the Felix Dzerzhinsky Higher School of the KGB located in Moscow. As can been seen in the articles from the KGB’s classified in-house academic journal Papers of the Higher School of the KGB, considerable attention was devoted to the cultivation of what were described as “Chekist” values: unquestioning loyalty to the Soviet Communist system and its defense from foreign and domestic adversaries.[1]

But what if someone were to be recruited into the KGB without having graduated from the Higher School in Moscow or from one of its branches in the other Soviet Socialist Republics? Was this even possible and, if so, what kind of study and training would this individual have to go through? In other words, could one be trained for the Chekist profession independently from the Chekist educational institutions?

A secret document from the archive of the Lithuanian KGB provides answers to these questions. I have translated this document into English and published it on DigitalArchive.org.[2] The document was produced by the regional branch of the Lithuanian KGB from the northern Lithuanian town of Pasvalys on the river Svalia. Today Pasvalys is a small farming town best known for its beer and cheese. There is no evidence that it was the source of any major security concerns during the Soviet era, except in the immediate post-WWII period when the local Lithuanian partisans fought against the Soviet troops.[3]

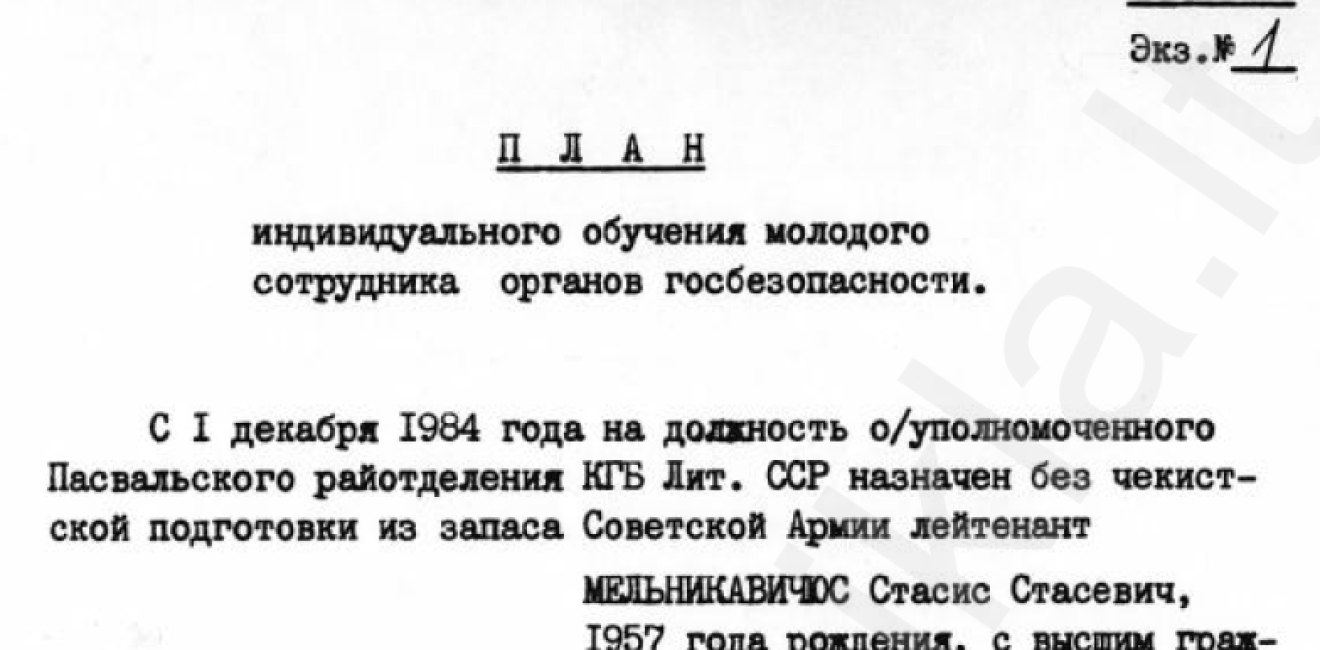

However, the document in question came into being almost four decades later, in December 1984, and has no direct relation to those events. Titled “A Plan for the Individual Training of a Young Officer of the State Security Service,” the document provides a set of instructions concerning the matters that a newly-recruited state security officer who has not gone through the Chekist educational system needs to know in order to perform his Chekist duties in the successful manner. As such, the document offers a fascinating insight into the fundamentals of Chekism. Essentially, it is a course syllabus for Chekism 101.

The officer in question is named Stasis Stasevich Melnikavičius. He is 27 years old, a university graduate, a member of the Soviet Communist Party, and comes to the KGB from the Army Reserve where he had the rank of a lieutenant. It is likely that he was a native of Pasvalys and was well-known to the regional security service leadership as a young, devoted Communist. It is also likely that someone from his immediate family was closely connected to the state security. This would explain how Melnikavičius could be recruited by the regional KGB branch without having any previous Chekist training. Even so, the issue of his lack of training could not be allowed to linger on for long. Not even a week after Melnikavičius started his new job on December 1, 1984, the chief of the regional branch, Lt. Colonel S. Saveikis signed a detailed plan instructing Melnikavichius’ immediate supervisors how to remedy the situation.[4]

First of all, Melnikavičius’ training was to include both theoretical and practical components. The theoretical component included the close familiarization with the executive orders of the KGB dealing with the main areas of the security officer’s daily job: working with agents and trusted persons and filing reports for superiors. It is to be noted that the executive orders that the document specifically mentioned included the two from the previous year (1983), which implies that the KGB was in the process of reforming its procedures and trying to improve the manner in which it conducted these activities.

In addition, the theoretical component included an intensive and sustained focus on seven specific areas of study designated as “topics.” The topics ranged from the procedures related to the selection, recruitment, and work with agents and trusted persons (two distinct categories of informers in the KGB terminology, with the latter being more informal and typically not paid for their services) to the general measures on political and ideological vigilance given the vectors of international and domestic politics and the dynamics of the Cold War in the 1980s.

The practical component encompassed the assessment of Melnikavičius’ abilities to fill out and file all the necessary reports related to his daily activities. According to the document, this assessment was to be made via “regular conversations” initiated by Melnikavičius’ immediate supervisors.

Interestingly, these “conversations” were also intended to go beyond the complexities of the daily tasks and to involve the references to what the document described as “the glorious Chekist war and post-war traditions.” In this way, Melnikavičius was supposed to be brought into contact with the idealized images of the Chekists as role models to inspire him to be a loyal and disciplined cog in the Chekist machine. As a source for these references, the document suggested the KGB in-house bi-monthly journal Sbornik as well as the variety of Chekist-sponsored popular culture products (novels and films) but without naming any in particular.[5]

It is not known how well his independently acquired Chekist education served Melnikavičius in carrying out his daily duties, how many agents and trusted contacts he recruited, or how many anti-Soviet plots he broke up in the flatlands of northern Lithuania. The top secret Pasvalys KGB regional branch annual report for the year 1985 (the first full year of Melnikavičius’ Chekist employment) reveals that the branch had 36 agents, two of whom were recruited during the course of that year in addition to the recruitment of one owner of a safe house apartment.[6] However, it is not stated who recruited them nor who was in charge of running them. The same absence of the recruiting officers’ names is also found in the other Pasvalys KGB regional branch annual reports available in the Lithuanian KGB archive.

There is, however, an additional trace of Melnikavičius’ activities found in the archive. It is a short, undated handwritten note he addressed to the chairman of the Lithuanian KGB, Maj. General Eduardas Eismuntas giving his assent to being transferred to another KGB regional branch in the town of Skuodas.[7] Skuodas is located in northwestern Lithuania about 130 miles west of Pasvalys and is 50 miles away from the major Lithuanian port city of Klaipeda. It is slightly smaller than Pasvalys, so it is not clear whether this was to be considered a promotion or not. Still, Melnikavičius seems to have been happy with it. Now in the rank of a captain, he informed Eismuntas that his wife had nothing against the move and that she also did not mind the fact that for a time he would have to leave his family behind.

The transfer might have turned out to be a smart career move for Melnikavičius, if not for the larger domestic and international forces that were shaking up the Communist status quo in Lithuania in the late 1980s. Less than a year after his announced move to Skuodas, Lithuania declared itself a sovereign, independent state and the days of the Lithuanian KGB were numbered. In contrast to the majority of Lithuanians, the independently-educated Chekist captain Melnikavičius faced a bleak future. The archive says nothing about his post-Soviet fate.

[1] See, for instance, полковник В.А. Золототрубов [Colonel V.A. Zolototrubov], “Дальнейшее укрепление дисциплины - важнейшее условие подготовки чекистких кадров [The Further Strengthening of Discipline – The Most Important Condition for Training Chekist Officers]” Труды Высшей Школы 11 [Papers of the Higher School of the KGB, Volume 11]. Moscow, 1976, pages 238-253; подполковник А.Д. Ионин [Lt. Colonel A.D. Ionin], “Некоторые методические проблемы совершенствования содержания специальных учебных дисциплин в чекистском вузе [Some Methodological Questions Regarding Content Improvement of Special Study Disciplines at the Chekist University]” Труды Высшей Школы 14 [Papers of the Higher School of the KGB, Volume 14]. Moscow, 1977, pages 170-182; Кандидат юридических наук подполковник В.Ф. Шмелев [Law PhD Lt. Colonel V.F. Shemlyov] “Формирование у слушателей чекисткого характера военного контрразведчика в процессе преподавания специальной дисциплины 5 [The Formation of the Chekist Character of the Military Counterintelligence Officer Among the Students in the Process of Teaching Special Discipline No. 5]” Труды Высшей Школы 30 [Papers of the Higher School of the KGB, Volume 30]. Moscow, 1983, pages 329-345. All these articles were classified as top secret. The print run of the Papers in the 1980s was 350 copies per volume.

[2] “Секретно: ПЛАН индивидуального обучения молодого сотрудника органов госбезопасности [Secret: A Plan for the Individual Training of a Young Officer of the State Security Service], December 7, 1984, Lithuanian Special Archives, f. K-11, ap. 1, b. 2357, l. 1 - 3, first published by The Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, http://www.kgbveikla.lt/docs/show/4960/from:664.

[3] In this context, the archive contains the documents related to the case of Juozas Cibulskis, a Pasvalys region native, sentenced to death for the anti-Soviet “terrorist” activities in November 1951 whose sentence was later commuted to 25 years in prison. Released in 1957, Cibulskis returned to the Pasvalys region in 1974. He was known for his anti-Soviet views and was a subject of the extensive Pasvalys regional branch surveillance. See “LSSR KGB Pasvalio r. skyriaus viršininko pplk. S. Saveikio pažyma apie operatyvinės stebėjimo bylos (DON) Nr. 1857 objektą J. Cibulskį [The LSSR KGB Pasvalys Regional Branch Chief Lt. Col. S. Saveikis' Report on the Operational Surveillance File of the Object No. 1857 J. Cibulskis],” December 30, 1983, Lithuanian Special Archives, f. K-1, ap. 46, b. 2648, l. 34, first published by The Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, http://www.kgbveikla.lt/docs/show/2904. There is also a document detailing the KGB plan for the arrest of Cibulskis in June 1987. See “LSSR KGB Pasvalio r. skyriaus viršininko kpt. R. Gabalio operacijos planas dėl J. Cibulskio suėmimo [The LSSR KGB Pasvalys Regional Branch Chief Capt. R. Gabalis' Operational Plan for the Arrest of J. Cibulskis], June 9, 1987, Lithuanian Special Archives, f. K-1, ap. 46, b. 2648, l. 35-36, first published by The Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, http://www.kgbveikla.lt/docs/show/2905.

[4] Lt. Colonel S. Saveikis was the head of the Pasvalys regional branch until the spring of 1987 when Captain R. Gabalis was appointed to that position. Gabalis was in charge of the Pasvalys regional branch at least until the spring of 1990. There is a document bearing his signature dated February 1990 which shows that in the meantime he had been promoted to the rank of a major. See “LSSR KGB Pasvalio r. skyriaus mobilizacinės veiklos dokumentų aprašas [The LSSR KGB Pasvalys Regional Branch Description of Its Mobilization Activities], February 8, 1990, Lithuanian Special Archives, f. K-1, ap. 46, b. 2648, l. 1 - 3, first published by The Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, http://www.kgbveikla.lt/docs/show/2901.

[5] For the discussion of the Sbornik, see Victor Yasmann, “The KGB Documents and the Soviet Collapse: A Preliminary Report” (Washington, DC: The National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, 1998); Victor Yasmann and Vladislav Zubok, “The KGB Documents and the Soviet Collapse: Part II” (Washington, DC: The National Council for Eurasian and East European Research, 1998), and Sanshiro Hosaka “Repeating History: Soviet Offensive Counterintelligence Active Measures,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence (2020).

[6] “LSSR KGB Pasvalio rajono poskyrio 1985 metų veiklos ataskaita, statistiniai duomenys, agentūra [The LSSR KGB Pasvalys Regional Branch 1985 Activities Report, Statistics, Agent Networks], December 13, 1985, Lithuanian Special Archives, f. K-11, ap. 1, b. 2357, l. 44-56, first published by The Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, http://www.kgbveikla.lt/docs/show/1529.

[7] “LSSR KGB Pasvalio r. skyriaus operįgaliotinio kpt. S. Melnikavičiaus raportas KGB pirmininkui gen.-mjr. E. Eismuntui [The LSSR KGB Pasvalys Regional Branch Captain S. Melnikavičius’ Note to the Chairman of the KGB Maj. General E. Eismuntas],” 1989, Lithuanian Special Archives, f. K-11, ap. 2, b. 918, l. 10, first published by The Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, http://www.kgbveikla.lt/docs/show/4959. The note makes a reference to June 1989 which means that it was written sometime after that.