Churchill and India: Manipulation or Betrayal?

With over 2,000 books on Winston S. Churchill, why another? Here’s a good reason: No one has studied the story of Churchill’s relationship with India in its entirety

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

With over 2,000 books on Winston S. Churchill, why another? Here’s a good reason: No one has studied the story of Churchill’s relationship with India in its entirety

With over 2,000 books on Winston S. Churchill, why another? Here’s a good reason: No one has studied the story of Churchill’s relationship with India in its entirety. That’s the subject of my new book, Churchill and India.

Where did Churchill’s bitter hatred for India and Hindus originate? Let’s briefly examine why.

Churchill went to India with his cavalry regiment, the 4th Hussars, from 1896-1899. Spending 22 months “in country,” this was Churchill’s longest foreign sojourn. From Bangalore, Churchill complained to his mother that the only people he met were soldiers, and they were “as ignorant” about conditions in India as he was. He disliked British “old India hands,” like Indian Civil Service officials, who understood the country; many were erudite scholars. Churchill was put off by their social customs such as hierarchy-driven “calling” (exchanges of visits), which were so different from London society’s practices. His knowledge of India remained superficial.

Churchill worshiped his father, Lord Randolph. He died in 1895 after a prolonged illness, becoming a lifelong lodestar. Churchill bought wholesale those Victorian values. He then discovered himself through self-study, having missed university education. He thirsted for knowledge. He read voraciously, especially the classics plus books his father had recommended. And he reflected. That forged his core values, including a permanent passion for “defense of Empire.”

Random events cast long shadows. In 1897, going nominally as a war correspondent in uniform, Churchill joined in brutal Afghan mountain combat with Pathan tribesmen, even hand-to-hand fighting. This is brilliantly depicted in his first book, Malakand Field Force (1898). He was sent from the frontline to temporary duty with an Indian regiment, composed of Muslim soldiers. At that time Indian troops (under their own British officers) and British regiments were strictly segregated. That became his only exposure to “real India,” producing lifelong empathy for Muslims. Later, that morphed into political support for Jinnah and his Muslim League.

Churchill’s dealings with Indian servants, moneylenders, and petty merchants were open; he described these with humor. During his 1907 six-month East Africa safari, Churchill showed sympathy for the Indians who had come as laborers and traders. On July 8, 1920, endorsing in Parliament the removal from the Army an officer who led the 1919 massacre at Jallianwala Bagh, he called it a “monstrous event” without parallel.

Churchill’s views of India began to change after 1919. British moves after WWI that allowed elections to new entities with limited power drew his antipathy. A key point was the 1921-22 visit to India by the Prince of Wales (later King George V), which coincided with Gandhi’s first Satyagraha movement against British rule. It alarmed Churchill. Katherine Mayo’s 1927 book Mother India, a one-sided attack on Hindu society and heritage, gave Churchill that sharp edge and vocabulary. It produced prejudice, racism, and hatred for all Hindus (“beastly religion, beastly people”). For him, India’s freedom movement personified those defects.

In October 1929, Churchill entered 10 years of political wilderness. Going against his own Tory Party, and other major parties, he stridently attacked India’s gradual evolution to self-rule. Four years later, asked why he did not abandon this, Churchill replied: He would not remain in politics or actively participate “if it were not for India.” A consequence: his prescient warnings, commencing in 1933, on the rise of Nazi Germany went unheeded.

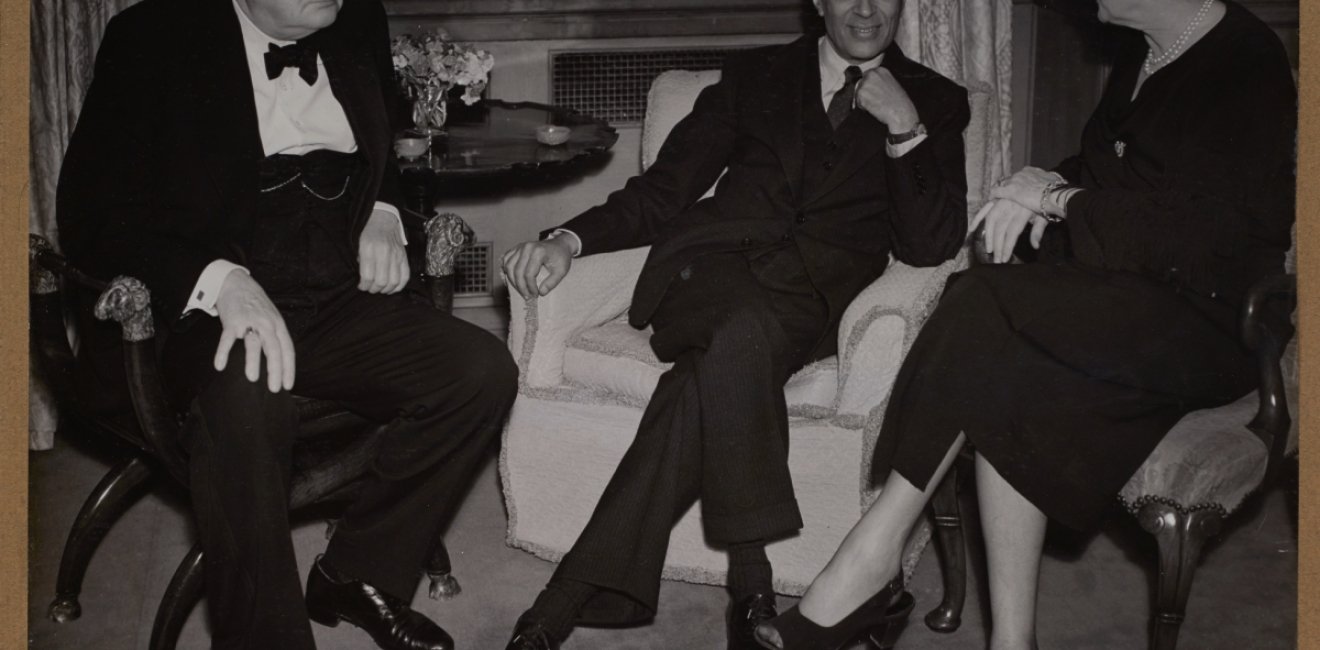

Britain and the West rightly celebrate Churchill as an inspiring wartime prime minister (between February 1940 and August 1945). But a “dark side” of unreason and denial dominated his India outlook. Fixation on the “Empire” led him to fantasy and misgovernance, plus great pain for India. President FD Roosevelt (FDR) worked hard from 1940 until 1942 to get Churchill to accept the looming postwar reality of self-rule in the colonies. Just before their White House Summit of December 1941, FDR told Eleanor that he would “have to compel” Churchill to give dominion status to India, but that failed. Churchill was unmoved. After extended cajoling, FDR gave up by late 1942.

Unable to counter the Indian freedom movement’s high tide, Churchill lapsed into ostrich-like denial. He imprisoned Indian leaders for nearly three years from 1942 until 1945. That sundered political dialogue, which could have offered compromise. With the end of WWII in sight, Churchill refused to consider an orderly transfer of power. And throughout, Jinnah and his Muslim League were patronized, built up to create a new state as a future strategic ally to block Soviet access to the Arabian Sea and safeguard oil supplies.

How can we forget the 1942-1944 Great Indian Famine, which killed three million? It originated with blocked Burmese rice supplies, poor rains, destruction of rice stocks in East India in early 1942 by the British Army (fearing a Japanese invasion), and hoarding of food grains by Indian traders – all compounded by the incompetence of British India officials. Churchill did not heed that crisis. Not one “Action This Today” edict went to an incompetent Viceroy Linlithgow. Futile buck-passing between Delhi and London ensued, over shipping to bring food grains offered by Australia and Canada. It is the darkest event under Churchill’s watch.

As for Churchill-Jinnah links, we find tantalizing bits of information, not conclusive in themselves, adding up to a suggestive partial picture. The first bit of Churchill-Jinnah correspondence in the Churchill Archives is from 1945, after Churchill left the premiership. I found in the British National Archives Jinnah’s January 2, 1941, letter, and his telegram of January 4, plus Amery’s reply on behalf of the PM. The banal tones suggest a mutual familiarity. Churchill-Jinnah exchanges don’t figure in the meticulous Amery Diary, clearly an out-of-bounds theme.

In the early 1940s, Churchill predicted a Hindu-Muslim bloodbath at Partition. That became his self-fulfilling legacy after he lost the August 1945 election. Labour PM Clement Attlee pushed through an unprepared, over-hasty but inevitable division of British India.

My new book offers new accounts of known events, with documents and other material confirming Churchill’s betrayal of human values.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more