I recently discovered reading a real estate advertisement that my neighborhood – D.C.’s West End -- was being “redefined.” I suppose that it is. Certainly development long ago “redefined” the area’s historic African American community out of existence. I wonder who might be next.

A once noteworthy blue collar neighborhood, the West End had fallen into disrepair by the 1970s after having been targeted for demolition to make way for an inner beltway circling downtown. Investment and property values fell despite the area’s convenient location between Dupont Circle and Georgetown. The neighborhood came on-line again once highway planners lost their battle to plough an interstate highway through the front door of the Luxembourg Embassy.

The preparation of a neighborhood renewal plan that was released in 1972 was an early signal that developers would take an interest in this tired section of town. Issued by the District’s Office of Planning and Management, the plan envisioned a “new town for the West End”; which is precisely what would happen over the next several decades.

“Urban pioneers” quickly followed the cessation of highway planning. Area buildings soon filled up with the 1970s version of today’s millennials. Over time, as people came and left, new residents once were undergraduate students. They were replaced by grad students. Similar transitions followed every half-decade or so as grad students were followed by professional school students, and then lawyers and World Bank economists. The story is a model of great success from the perspective of District officials, planners, and developers. This was not always the case for those who lived in the neighborhood before.

Precise moments are readily apparent in the transition from a neighborhood of African American wage earners to one with the embassies of Qatar and Spain, a Ritz Hotel, and a Trader Joe’s. For example, on one area side street mid-way through the 1970s, the first white resident moved into what had been a completely African American community for decades. The entire neighborhood came out to help him move in as is the tradition in African American Washington. When everyone was done and a neighborhood cookout ensued to celebrate, he overheard one of his new friends ironically declare, “There Goes the Neighborhood.”

A more true prediction could not have been uttered. Within just a couple of years, poorer African American renters had been forced out by condominium conversions and rising rents. Many African American homeowners held on, aging in place. Their children and relatives had scant interest in keeping their houses once their parents, aunts and uncles had passed on. Within a decade or two not a single African American resident remained. Meanwhile, “historically accurate” brick sidewalks and street lamps have replaced towering stanchions with super-charged anti-crime lights glaring down on cracked cement sidewalks. Long abandoned fire call-boxes became art projects.

There now are precious few reminders of what the West End had been before. A post office substation marks Duke Ellington’s Ward Place birthplace; the historic African-American Francis-Stevens School has become an “education campus;” the façade of an apartment building that once housed African American staff for the White House remains despite the construction of a pricy apartment building on the rest of its site; and those who know what to look for can still find the Secret Service motor pool. Otherwise, virtually nothing can be found of the historic African American West End.

Washington, D.C. has lived through almost seven decades of gentrification, beginning with Georgetown in the 1940s and continuing until today when it is reaching Brookland and beyond. Much has been gained. Washington has become a safer, more interesting, and more vibrant city. However, as the story of the West End reveals, much has been lost.

Argentine novelist Manuel Vázques Montalbán once wrote that “triumphant cities smell of disinfectant.” Contemporary Washington’s challenge has become how to embrace pioneers of every race, gender, creed, and generation without having them become colonizers. The city appears to fail at this challenge at least as much as it succeeds. The odor of disinfectant becomes more pronounced in Washington every day.

Author

Former Wilson Center Vice President for Programs (2014-2017); Director of the Comparative Urban Studies Program/Urban Sustainability Laboratory (1992-2017); Director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies (1989-2012) and Director of the Program on Global Sustainability and Resilience (2012-2014)

Urban Sustainability Laboratory

Since 1991, the Urban Sustainability Laboratory has advanced solutions to urban challenges—such as poverty, exclusion, insecurity, and environmental degradation—by promoting evidence-based research to support sustainable, equitable and peaceful cities. Read more

Explore More in Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Browse Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Hometown D.C.: America's Secret Music City

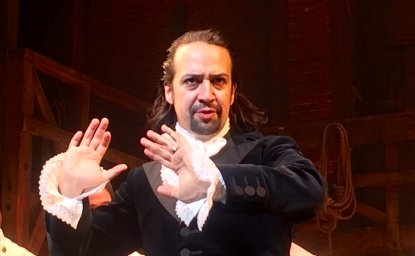

Bringing New York to the Broadway Stage

10 Steps to a More Genuine DC Experience