Desert Mystery: Intelligence Assessments of Israel’s Nuclear Program

The CIA missed Dimona, but their peers fared worse.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

The CIA missed Dimona, but their peers fared worse.

The CIA missed Dimona, but their peers fared worse

Israel’s nuclear program is unique: foreign intelligence agencies extensively evaluated its progress during the Cold War, yet we understand only the outlines of its overall history. As part of its “opacity” policy, Israel refuses to admit to developing weapons at its nuclear facility near the desert town of Dimona, whose name came to stand for the entire nuclear program.

My dissertation research compares how Cold War-era intelligence agencies evaluated the nuclear programs of other countries. With the benefit of hindsight, we can compare these historical evaluations to one another and to the contemporary consensus on Israel’s nuclear program.

The United States was especially eager to understand Israel's nuclear capabilities and intentions, but struggled to do so. Two years ago, historians Avner Cohen and Bill Burr released several documents chronicling the inglorious frustration among friends:

The Eisenhower administration's "discovery" during the last months of 1960 that Israel was secretly building a large nuclear complex at Dimona was a belated one indeed. It occurred more than five years after Israel had made a secret national commitment to create a nuclear program aiming at providing an option to produce nuclear weapons; more than three years after Israel had signed its secret comprehensive nuclear bargain with France; and two years or more after Israel had begun the vast excavation and construction work at the Dimona site…

What amounted to an intelligence breakdown by the United States was a tremendous counterintelligence success for Israel. The U.S. bungle enabled Israel to buy precious time for the highly vulnerable Dimona project. One could argue that had the United States discovered Dimona two years earlier, perhaps even a year earlier, that the young and fragile undertaking might not have survived. Early political pressure from the United States on the two foreign suppliers, France and Norway, might have terminated it at the very start.

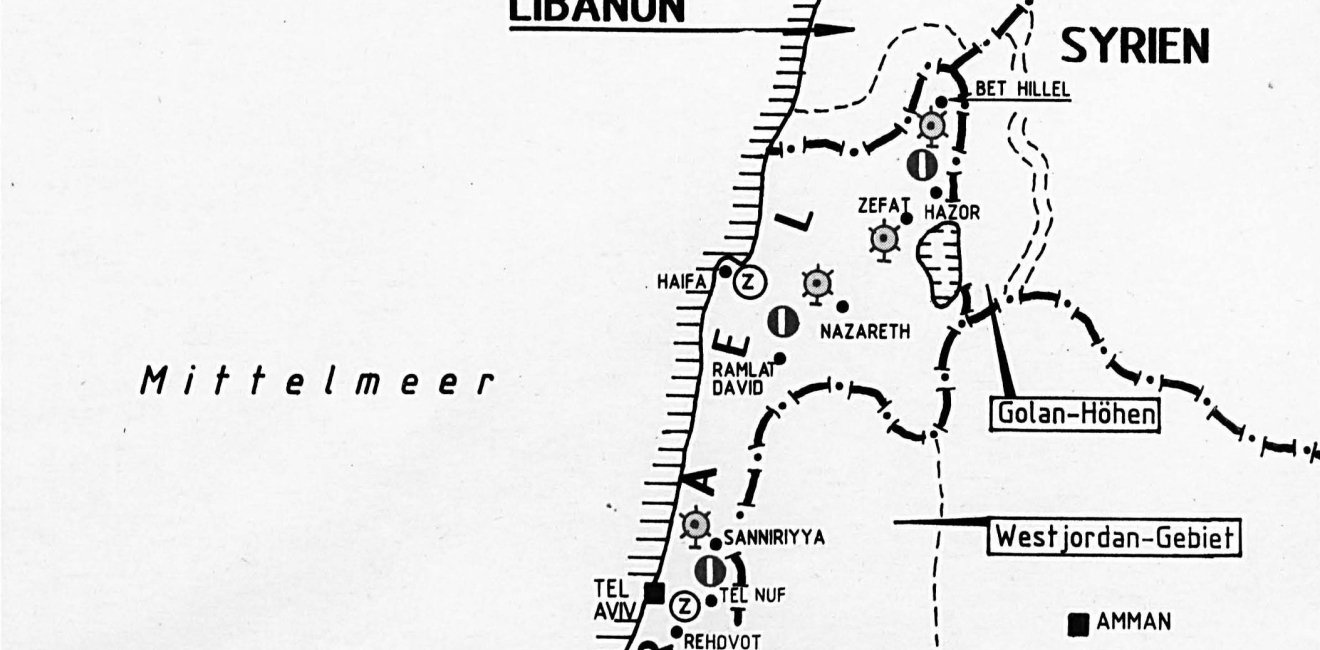

Other intelligence agencies, like the West German Federal Intelligence Service (BND), did not fare better. In 1974, all the BND could tell the German Chancellor was that the Israelis would have had enough plutonium after 1970 to make four or five bombs. The BND remained in the dark despite multiple inquiries, only updating its estimate of plutonium stocks to being equivalent to 15 bombs in 1981. As late as 1985, an intelligence briefing for the trade minister noted press reporting about Israeli possession of operational nuclear weapons, but that the BND had yet to find proof.

Analysts on the other side of the wall performed even worse. Handicapped by unfriendly bilateral relations and smaller resources, East German spies found that their best sources on Israeli nuclear weapons to be their many connections in the West German government. In 1970, the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) used its own information to confirm Israel’s ability to build weapons, but relied on Western government sources to speculate that it had operational warheads (it doesn't appear that they had procured the actual BND assessments).[1] A decade later, the Stasi still relied on foreign opinions, including an Indian defense ministry's internal investigation.[2]

The East German military intelligence service was less circumspect, announcing in 1988 that Israel had precisely 20 warheads that would be ready for use immediately or at least within days. This did not convince their peers at the MfS, which continued to profess uncertainty all the way to its deathbed.

As with declassified US documents, the UK is especially protective of intelligence reporting on Israel. Global proliferation overviews began to mention Israel in 1961:

Israel began an enlarged atomic energy program in 1956-57. There is reason to suppose that its purpose was partly military, and the installations now being built could, when complete, be put to military use unless this were prevented by pressure from outside. It would be technically practicable for the Israelis to hold a nuclear test in 1965, provided they can acquire safeguard-free uranium and they are prepared to disregard world public opinion.[3]

Another cursory summary followed four years later:

The Israelis are close to putting themselves into a position to manufacture nuclear weapons. Sufficient plutonium could be available for a first test about two years after a decision, the earliest possible date being the and of 1966. However, Israeli political leaders are likely to adhere as long as possible to the view that the military balance between Israel and the Arab world can be maintained without nuclear weapons.[4]

A 1973 assessment expressed great uncertainty about Israeli nuclear intentions and capabilities:

We cannot ignore the possibility that Israel may possess enough fissile material and the design capability to produce a few low yield weapons very quickly and without testing. These could be delivered by her fighter-bombers, and she may already have surface-to-surface missiles which would make most sense if they carried nuclear warheads. If for example, she thought that increasing United States dependence on Arab oil would reduce the amount of American assistance on which she could count in any future conflict she might consider it necessary to have an independent nuclear deterrent.[5]

After this report, the British records become elusive. A registry of reports produced by the department that evaluated nuclear programs is redacted in several places. I suspect that most of the censored report titles relate to Israel. Another conspicuous omission is a 1980 military intelligence report on Israel, which lists military assets from inland waterways (none) to oil storage capacity (plenty), without ever mentioning nuclear weapons.[6]

Would it have mattered if these intelligence agencies had provided earlier warning to their governments that Israel was working to build nuclear weapons? Yes. Early detection expands the range of counter-proliferation options, as Israel itself understood in its persistent campaign against Iraq's nuclear program.

[1] Ausgangsinformation der HV A des MfS Reihe: (Einzel-) Informationen, Nummer: 834/70 Archivsignatur: BStU, MfS, HV A 170, Bl. 326-327 and Ausgangsinformation der HV A des MfS Reihe: (Einzel-) Informationen, Nummer: 90/70 Archivsignatur: BStU, MfS, HV A 159, Bl. 58-62 [Sonderfassung]

[2] Ausgangsinformation der HV A des MfS Reihe: Wirtschaftspolitische Informationsübersichten, Nummer: 5/80 Archivsignatur: BStU, MfS, HV A 86, Bl. 259-274

[3] "Development of Nuclear Weapons by Fifth Countries during the Period up to 1970" JIC (61) 31 (final) September 1961 in CAB 158/43

[4] "The Development of Nuclear Weapons by Additional Countries 1965-1975" JIC (65) 25 (Final) July 1965 in CAB 158/57

[5] “Development of Nuclear Weapons by Additional Countries up to 1980” JIC (A) (73) 15 in CAB 186/15

[6] Intelligence Briefing Memorandum on Israel, August 1980, Ministry of Defence, Defence Intelligence Staff (Logistics Intelligence Branch), D/82/IBM in DEFE 62/5

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more