A blog of the Wilson Center

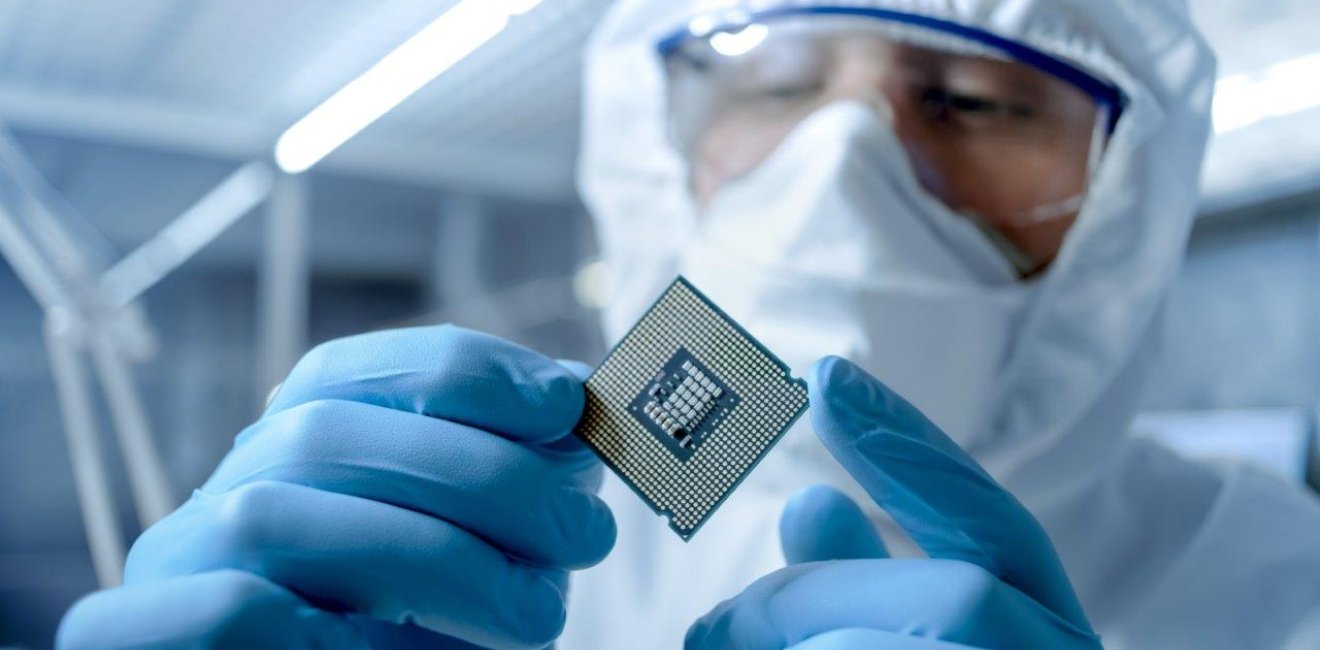

In 2020, dollar-for-dollar, China imported more in semiconductors than it did in oil.

The People’s Republic of China, or PRC, is the world’s largest importer of crude oil, and since 2005, it has been the world’s largest importer of semiconductor chips—which are essential to products like smartphones, computers, and telecommunication equipment. In 2020, the PRC’s reliance on imported semiconductors amounted to a $233.4 billion trade deficit, while that same year the country’s crude oil trade deficit was “only” $185.6 billion.

The heart of the semiconductor industry is located in Taiwan, just 100 miles from the PRC’s shores, and by far the largest producer of advanced semiconductors. In fact, TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.) alone is responsible for 60% of production for semiconductors and as much as 90% production for advanced semiconductors.

But as the Wilson Center’s influential report Of Swans and Rhinos explains, the semiconductor supply chain is a complex, global industry, with chips crossing international borders many times before coming to market, bringing direct implications for reshoring, nearshoring and, increasingly, export controls. While Americans naturally view the status of Taiwan through a bilateral lens, it’s important to remember that, despite the obvious government-to-government distrust between Taipei and Beijing, the PRC is Taiwan’s largest trading partner…much larger, in fact, than it is with the US. Taiwan’s other top trading partners include Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Malaysia, and Vietnam…all countries that need Taiwan’s semiconductors for their own economic growth and security.

The intensifying US-China rivalry, uncertainties in Beijing’s treatment of foreign businesses operating in China, pressures on business to address supply chain vulnerabilities, and the impact of industrial policies emerging from Washington and elsewhere are increasingly making business operations in the region a “high wire act.”

In October 2022, with cooperation from Japan, the Netherlands, and the Republic of Korea, the US enacted a series of export control regulations aimed at limiting American sales of semiconductors to China and preventing Chinese companies from buying chip-making equipment from the US without a license. The Biden administration justified its actions as necessary for America’s national security interest, and firmly stated that its goal was not to hold China back more broadly or to decouple the US and Chinese economies. Unsurprisingly, Beijing sees things differently, and argues that these restrictions are a thinly disguised effort to deny Chinese access to technologies essential for its economic growth and development, including plans to bolster its domestic semiconductor production capacity.

Before the new restrictions, the US only banned the sale of semiconductors and the tools required to make them to PCR military entities. The newer controls are far more sweeping: Advanced semiconductors and chips are restricted from being sold to any Chinese entity; the equipment and machines needed to make semiconductors created in the US are restricted from being sold to Chinese entities; and sales of other key US manufactured technology components like precision lasers or mirrors are sharply limited.

While it could do far more damage to the US by restricting critical minerals—which it can’t do without causing great harm to its own interests—China responded by restricting the export of two metals key to the manufacturing of semiconductors, gallium and germanium compounds. Gallium is used to produce compound semiconductor wafers and germanium is used in the manufacturing of certain fiber optics. China is the world’s largest source of both of these critical minerals.

While the impact of all this is not yet certain, and the world is still feeling the effects of economic turbulence from the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s worth noting that in 2022, China’s importation of semiconductors and integrated circuits actually declined from the previous year. In fact, in November 2022, the PCR’s semiconductor imports were at their lowest level since 2020. And as the aforementioned Wilson Center report shows, the complexities of global technology production mean that what happens (or doesn’t happen) in China, the US, Vietnam, India or numerous other locations, rarely stays there.

Final thought: for many decades, a rallying cry of antiwar activists was “no war for oil.” In modern times, a new plea might be aimed at semiconductors and critical minerals.

This blog was researched and drafted with the assistance of Caroline Moody.

Author

Explore More in Stubborn Things

Browse Stubborn Things

Spying on Poachers

China and the Chocolate Factory

India: Economic Growth, Environmental Realities