A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

The conventional wisdom states that the U.S.-India partnership, due to the bipartisan support it enjoys in Washington, is not likely to experience many notable differences now that there is a new occupant in the White House.

This is a case of the conventional wisdom being correct. But we also shouldn’t overlook some notable changes that are likely to emerge.

On a very general and macro level, there won’t be that many differences. The relationship, impelled by intensifying cooperation in the security sphere, will continue to gain momentum, just as it did in the Trump era. The bottom line is that The U.S.-India relationship, generally speaking, was going to be in a good place no matter who won the 2020 election. And that’s because there is strong bipartisan support in Washington for U.S.-India partnership, and there has been for several decades. The relationship has grown in a big way since the early 1990s, and especially since the early 2000s. That first boost came when Indian liberalization reforms and the end of the Cold War created new opportunities for cooperation on trade and energy, among other issues. The more recent boost came as shared concern over Islamist terrorism and more recently China’s rise has sharpened.

It’s also telling that a prominent Asia analyst and former Obama administration official, Kurt Campbell, has been appointed to the role of coordinator for the Indo Pacific at the National Security Council.

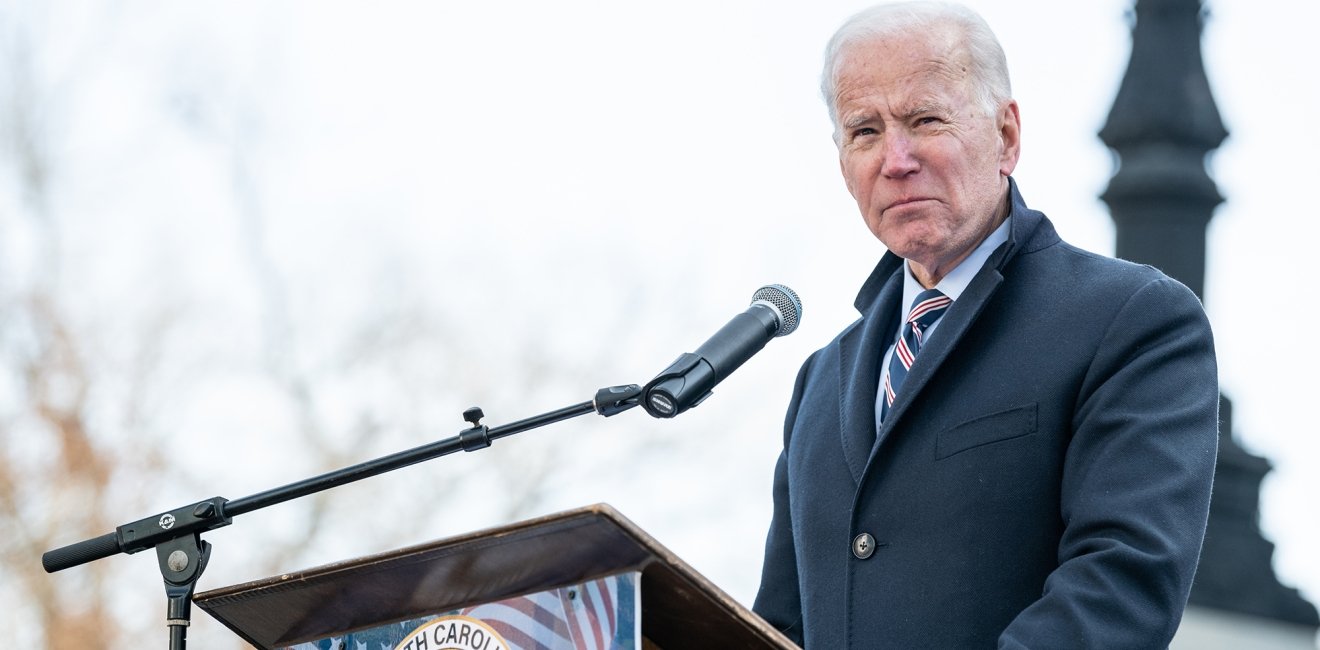

Biden himself is a long-time friend of India. He helped negotiate the U.S.-India civil nuclear deal, widely believed to be a major milestone for the relationship. He has described the U.S.–India partnership as the “defining relationship” of the 21st century. He has also often expressed his support for the Indian-American community, which has long been viewed as a bridge. In its early days, the administration has signaled that it will maintain a focus on two key areas of U.S.-India cooperation during the Trump years—the promotion of a “free and open Indo Pacific,” and also the strengthening of ties with two other close U.S. maritime partners in the region, Australia and Japan, as part of the “Quad” arrangement. An initial call between Secretary of State Antony Blinken and his counter part Dr S. Jaishankar hit on these themes. It’s also telling that a prominent Asia analyst and former Obama administration official, Kurt Campbell, has been appointed to the role of coordinator for the Indo Pacific at the National Security Council. That’s significant.

All this said, we can anticipate some notable changes in the U.S.-India relationship in the Biden era, with both positive and negative implications for the relationship.

Let’s first consider the positive changes that could soon emerge.

One is that the style and tone of Biden’s engagements with India, and the world on the whole for that matter, will be softer and kinder, as well as more consistent and predictable. This means India won’t have to worry about the possibility of impolitic distractions such as mocking remarks about India’s leaders (Donald Trump used to mock Narendra Modi’s accent), about Indian policies (Trump described India as a tariff king), or India’s policy challenges (Trump harangued India about its poor air quality). Based on conversations I’ve had with people close to the Indian government, the sense I get is that there is a strong measure of satisfaction among Indian officials that they’ll be working with a more traditional U.S. interlocutor. And this is important, given how much importance they place in their relationship with the United States.

A second likely change we will see is a willingness on the part of Washington to truly broaden the relationship into bigger issues, beyond hard security. The Biden administration places a lot of importance on borderless threats—climate change above all, but also cyberwar and pandemics. These are areas that the administration will want to focus on bilaterally with India, and multilaterally with India and other countries. Other broader areas that have the potential to take off are clean energy and IT cooperation. In the Obama era, there had been some forward movement with some of these spaces, but they were essentially put on the backburner over the last four years. Biden will want to get back to these areas. The new administration may well convene strategic dialogues—something the Trump administration chose not to do—that focus on these issues. The Biden administration may also encourage stepped-up exchanges on non-security issues on non-government levels—such as by supporting dialogues between business communities and academia on these topics.

On a related note, there will likely be an effort to get trade ties, which struggled in the Trump era, back on track. But we shouldn’t overstate an improvement in trade ties. Biden is no pushover on trade; he has indicated that he won’t sign any new trade deals unless there are guarantees on labor and environment. Keep in mind that he’s going to be focused on nursing the U.S. economy back to health, and he’s not about to quickly sign new trade deals that could be perceived as a threat to U.S. jobs or U.S. workers.

How about possible changes in the Biden era that could disadvantage the relationship? I do think we can expect the Biden administration not to hold back as much as the Trump administration did when speaking publicly about democracy issues in India. This is after all an administration that vows to make the strengthening of democracy a main pillar of foreign policy.

That said, we shouldn’t overstate the possibility of the Biden administration calling out India on democracy and rights issues. Even an administration that plans to wear the democracy promotion label on its sleeve will be selective in terms of which countries it calls out and which ones it does not. India is rightly perceived to be an important partner, and the administration will go relatively easy on it; it will not condemn India harshly in the way that it will lambast China or Saudi Arabia or Russia or other U.S. rival for their human rights violations. The Biden administration, like its predecessor, will not want to risk antagonizing such an important partner—and especially one that is highly sensitive to criticism abroad about its internal affairs.

One of Biden’s major concerns is Internet bans, and more broadly how technology and online tools are used in undemocratic ways. There’s been a fair amount of this in India of late.

But that doesn’t mean there won’t be gentle criticism. One of Biden’s major concerns is Internet bans, and more broadly how technology and online tools are used in undemocratic ways. There’s been a fair amount of this in India of late. I could envision some narrowly focused public comments from the administration that bring attention to the Internet bans that have taken place in Kashmir, and elsewhere. The State Department spokesperson recently brought attention to concern about Internet bans in areas where farmers’ protestors have been taking place, and it also congratulated India for lifting a very long Internet ban in Kashmir—thereby indirectly criticizing India for that ban.

We can expect some public criticism couched in diplomatic terms. For example, we could well hear Biden administration officials talk about how the US and India will work together to strengthen democracy at home and abroad—that’s a subtle way of prodding India without calling it out directly. Biden actually said something along these lines in an op ed he published in an Indian American newspaper just a few days before he won the election. He said, “We will meet every challenge together as we strengthen both democracies,” including freedom of expression and religion.

A second change we can expect in U.S.-India relations that isn’t necessarily a positive one relates to personal relationships. I don’t think personal chemistry among top leaders will figure as much in the Biden era as it did in the Trump and for that matter the Obama years. In this age of summitry and the personalization of diplomacy, these chemistry issues are important. This played out with the much ballyhooed “bromance” between Narendra Modi and Trump, two men who share much in common, and more surprisingly between Modi and Obama, two men who shared less in common.

Because of his focus on strengthening democracy and rights, Biden likely won’t want to be associated in a close and personal way with Modi, whose government has initiated crackdowns on dissent. This doesn’t mean Biden won’t want a good personal relationship with Modi, but he’ll likely want the focus to be less on the personal and more on the policy, and on working together toward common geopolitical goals in the Indo Pacific.

A third possible change in the relationship is that we could see some modest threats to the bipartisan nature of this relationship. In the Trump era, there was a fair amount of criticism on Capitol Hill against India for its crackdown on rights on Kashmir. Much of it came from Democrats. Now, under Biden, there is a White House that as noted earlier won’t shy away from some criticism of India, even if it’s relatively restrained. This could embolden Democrats on Capitol Hill and prompt them to intensify their own criticism.

An even modestly improved U.S.-China relationship may present a complication for New Delhi, which has seen its relations with Beijing plummet to their lowest point in decades...

One final potential change we could see in the U.S.-India relationship under Biden that could cause a bit of trouble for the relationship might emerge from Biden’s policies toward China and Russia. Biden, like Trump, will view China as a strategic competitor and threat. But he has vowed to pursue cooperation with China in areas, largely non-security spaces, where it is possible. An even modestly improved U.S.-China relationship may present a complication for New Delhi, which has seen its relations with Beijing plummet to their lowest point in decades, and has taken an increasingly hard line on China through reducing its commercial ties and scaling down other cooperation.

Russia could pose an even bigger issue for U.S.-India relations, given that U/S/-Russia ties are likely to get worse in the Biden era. Many Democrats view Russia through a bitter personal and emotional lens, as they believe that Russian election meddling propelled Donald Trump to his 2016 election victory. India’s longstanding friendship with Russia constitutes one of the few entrenched tension points in U.S.–India relations, at least from a geopolitical perspective. This doesn’t mean we should expect the Biden administration to place sanctions on India for the S400 deal with Russia, though we certainly can’t rule it out. This administration, like the previous one, will recognize that it can’t afford to sanction such a key partner. Still, the U.S.-India-Russia triangle may grow a bit more volatile.

This is not to overstate the negative impact these potential changes could have on the U.S.-India relationship. The relationship is in a very good place— in fact it’s arguably never been stronger—and in the Biden era such challenges can easily be weathered. So the bottom line is that we can expect, in the Biden era, for the pattern of the last 30 years to continue to play out: The U.S.-India relationship will continue to grow in an exponential fashion, regardless of who is in charge in the White House.

There will certainly be constraints—from lingering tensions over trade issues to India’s concerns about the U.S. relationship with Pakistan and America’s concerns about the Indian relationship with Russia to bigger and more strategic issues about New Delhi’s continued unwillingness to join the alliance system favored by the United States. And yet, these constraints would be there, no matter who is in the White House. And they won’t impact the general positive trajectory of the relationship.

This post is based on a presentation delivered to the UK-based Democracy Forum on February 16, 2021.

Follow Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Asia Program and senior associate for South Asia, on Twitter @MichaelKugelman.

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2020, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

Author

Indo-Pacific Program

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more