India’s Nuclear History, Frozen in Time

The melting Bossons glacier is revealing Indian government documents buried since the crash that killed Homi Bhabha in January 1966.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

The melting Bossons glacier is revealing Indian government documents buried since the crash that killed Homi Bhabha in January 1966.

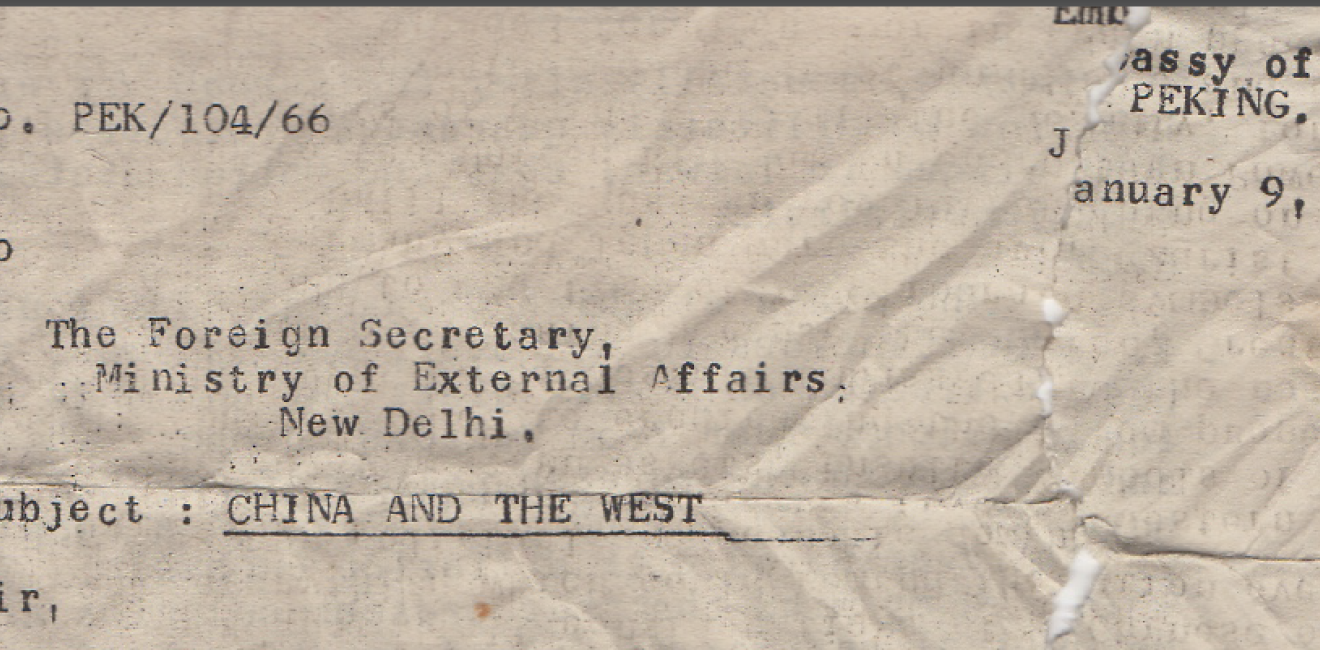

Above: Portion of a recovered document. Courtesy of Ms. Francoise Rey.

The melting Bossons glacier is revealing Indian government documents buried since the crash that killed Homi Bhabha in January 1966

Documenting accidents and disasters surrounding nuclear politics is always a challenging, uphill task. It is further complicated when the evidence has been buried under a glacier on Mont Blanc for fifty years.

Air India 101 Kanchenjanga (a Boeing 707) crashed on Europe’s tallest peak carrying India’s distinguished nuclear scientist, Homi Jehangir Bhabha, on January 24, 1966. All 117 passengers perished, and the plane’s flight data recorder was never found. Severe weather on the mountain meant that the bodies of very few victims were ever recovered.

Thanks to climate change, the Bossons glacier in Chamonix, France has been revealing pieces of India’s nuclear history: official documents marked “Top Secret” and “Secret” originating from the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, long buried with the wreckage of Air India 101.

Included among these documents are New Delhi’s assessments of Chinese defense and nuclear capabilities in early 1966. Some are Indian analyses of Chinese foreign policy, particularly Beijing’s relationship with the West and the Sino-Soviet split. If more can be found, these records from Chamonix could be a window into little-known Indian discussions on nuclear security guarantees during the Geneva-based negotiations at the Eighteen Nations Disarmament Committee (ENDC), which led to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.

The timing of the crash is essential to their historical value: the crash took place only three days prior to the beginning of the Ninth Session of the ENDC (27 January–10 May 1966). More importantly, India’s representative to the ENDC was Ambassador V.C. Trivedi, who was close to Bhabha and also New Delhi’s ambassador to Switzerland. In February 1966, less than a month after the crash, Trivedi gave his famous speech calling for nuclear security guarantees for India from the superpowers outside of alliance structures as a condition for signing the NPT. We still do not know what discussions within the Indian government precipitated this action—but the documents in Chamonix may hold clues.

I reviewed these documents during a recent meeting in Geneva with Françoise Rey, a Chamonix-based novelist who has researched the plane crash for several decades. Rey herself does not possess all the documents—they are scattered across residential homes in Chamonix and elsewhere. Some residents stumbled upon official Indian documents during their regular climbs to the glacier, others found them while looking for “treasures.”

In 2012, a 19.8-pound bag marked “Diplomatic Mail Ministry of External Affairs” was found and promptly returned to the Indian embassy in Paris. It contained newspaper reports from January 1966. Since then, the items found on the glacier have included precious jewels, an engine of the crashed Air India plane, human remains, and personal items of victims. However, it is not clear if all “discoverers” of the scavenged documents are willing to part with their glacial finds.

Perhaps, the appropriate next step is the creation of an “Archive of the 1966 Mont Blanc Crash” as a people’s repository. It could be a crowd-sourced platform, where Chamonix residents, mountain guides, mountaineers, treasure-hunters, enthusiasts, and visitors would photograph and upload items and documents that they chanced upon on the Bossons glacier, as a service to knowledge and scholarship. Histories of accidents and disasters, after all, are people’s histories.

Documents from the Air India 101 Crash Site

The author of this document, A.K. Damodaran, was a top Indian foreign policy official renowned for his expertise in Chinese and Soviet affairs. He went on to play a pivotal role in the 1971 Indo-Soviet Treaty that brought New Delhi at its closest to Moscow during the Cold War. This one-page document is addressed to Indian embassies and high commissions generally, and provides New Delhi’s assessment of Chinese defense production. It notes with frustration: “While every attempt has been made to make the estimates as objective and as accurate as possible, it has not been possible to leave out the speculative element completely because of the total absence of official statistics.”

This letter was sent to Foreign Secretary C.S. Jha in New Delhi from the Indian embassy in Beijing. It provides an Indian analysis of Chinese foreign policy, particularly, Beijing’s relationship with the West and the impact of Sino-Soviet split on Chinese foreign relations, and nuclear strategy. The document claims that Beijing was aware “that she is no longer treated as a sick giant but commands a healthy respect and a welcome fear from Western Europe.” It then adds in the context of the Sino-Soviet split, “the Chinese seem to have been quick to realize that the nuclear weapons and balance of terror provide a new freedom and flexibility for those countries which use their own limited strength in the local and peripheral context to advance their political purpose.” The above quote conforms to Indian concerns expressed to officials in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations that China might use nuclear weapons for ‘blackmail’ in its border dispute with India.

This document, which the author only saw parts of, is an Indian assessment of Chinese nuclear delivery capability. It states, “By the end of 1966, the size of the bomb could be reduced so that it becomes deliverable by an IL-28 light bomber. By the middle of 1967, China could have a nuclear-armed missile with a range of 1000 miles.” It is to be noted that the Ilyushin IL-28 was the first Soviet jet bomber that was widely used by China. However, after the Sino-Soviet split, China could not obtain the necessary licenses from Moscow, and therefore, began producing the IL-28 through reverse engineering as the Harbin H-5.

A longer and substantially different version of this account was published in The Diplomat on June 2, 2017. Neither the author nor Ms. Francoise Rey received financial compensation for this essay or the official documents used in this essay.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more