Jordan, the US, and the Cold War: The Birth of a Strategic Alliance

Patrick Ackerson explains the beginning of the Jordanian-American relationship and its significance from the Cold War to today.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Patrick Ackerson explains the beginning of the Jordanian-American relationship and its significance from the Cold War to today.

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has been a strong American ally for decades and has helped the US greatly during the Syrian crisis and battle against the Islamic State. Currently, the United States has an undisclosed number of military units in Jordan training the Free Syrian Army and supporting efforts against ISIS. These forces have engaged Bashar al-Assad's Syrian forces on at least one ocassion.[1]

How did the US develop such a close relationship with this Middle Eastern state? Jordan does not have the oil resources of the Gulf States, nor does it have access to the strategic shipping routes of the Persian Gulf. The key to understanding the relationship is in looking at its origins during the early Cold War. At a time of growing Soviet influence in the Middle East, the US found in Jordan and King Hussein a moderate, stable, and staunchly anti-communist partner who was willing to represent American interests in the region. In exchange, King Hussein gained the necessary support to shield against his own regional rivals. Born out of necessity, the Jordanian-American partnership has proven to be a truly symbiotic relationship that has lasted well beyond the Cold War and into today.

American involvement in Jordan began after World War II, but it was not until the Suez Crisis of 1956 that it began earnest. Following the British, French, and Israeli invasion of Egypt, the Jordanian ruler, King Hussein, could no longer count on a British alliance while maintaining the support of his public. Lacking the military or economic strength to defend itself from Israel, its Arab neighbors, or Soviet aligned forces without significant assistance from an outside nation. Hussein began looking for a new partner. After the British, the United States were the logical choice. Fortunately for Hussein, the US was also in the market for a regional ally.

Jordan and the United States found a mutual enemy in the socialist and nationalist ideology of Egypt's leader Gamal Abdel Nasser. Nasser led an Arab nationalist movement focused on uniting the Arab world under his leadership in opposition to the West and Israel. Nasser's rise challenged Western interests as well as moderate local governments like Hashemite regime in Jordan. When the Soviet Union offered to trade weapons for cotton with Egypt, the Eisenhower administration saw the possible deal as an immediate threat to the American position in the Middle East.[2] A National Intelligence Estimate issued on October 12, 1955 concluded that the continued movement of Nasser into the Soviet camp would imperil any Arab-Israeli settlement and block an anti-Communist regional defense pact. In addition, the estimate argued that the deal would "enhance the capabilities of local Communists for subversion and political penetration."[3]

To counter the increase in Soviet influence in the region, in 1955, the Americans aided British efforts to organize a Middle East defense pact between Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, and Turkey, known as the Baghdad Pact. While Egypt made it clear it would not join, the British and Americans hoped to add both Lebanon and Jordan to their ranks. However, Egyptian propaganda inflamed the Jordanian population against the proposed alliance and the leadership of King Hussein. Riots soon broke out in Jordan, which Hussein blamed on Nasser's interference.[4] Though Hussein believed that joining the pact had many important benefits, including increased military support and a chance to change the terms of the Anglo-Jordanian Treaty, the effectiveness of Nasser's propaganda prevented him from joining.[5] Still, Hussein clearly saw the US as his best option for coutnering the threats to his regime posed by Nasser and his Soviet supporters.

Even before the Suez Crisis, King Hussein demonstrated his aversion to communism and the threat it represented. In a meeting with Assistant Secretary of State Henry Byroade, Jordanian Foreign Minister Khalidy said, "Jordan was against communism. Jordan put people in jail for being Commmunists. ...And people like [me] hated communism." In a letter to Prime Minister Nabulsi in 1956, Hussein called Soviet-supported communism "a new kind of imperialism" and said, "If we are enslaved by this, we shall never be able to escape or overthrow it."[6]

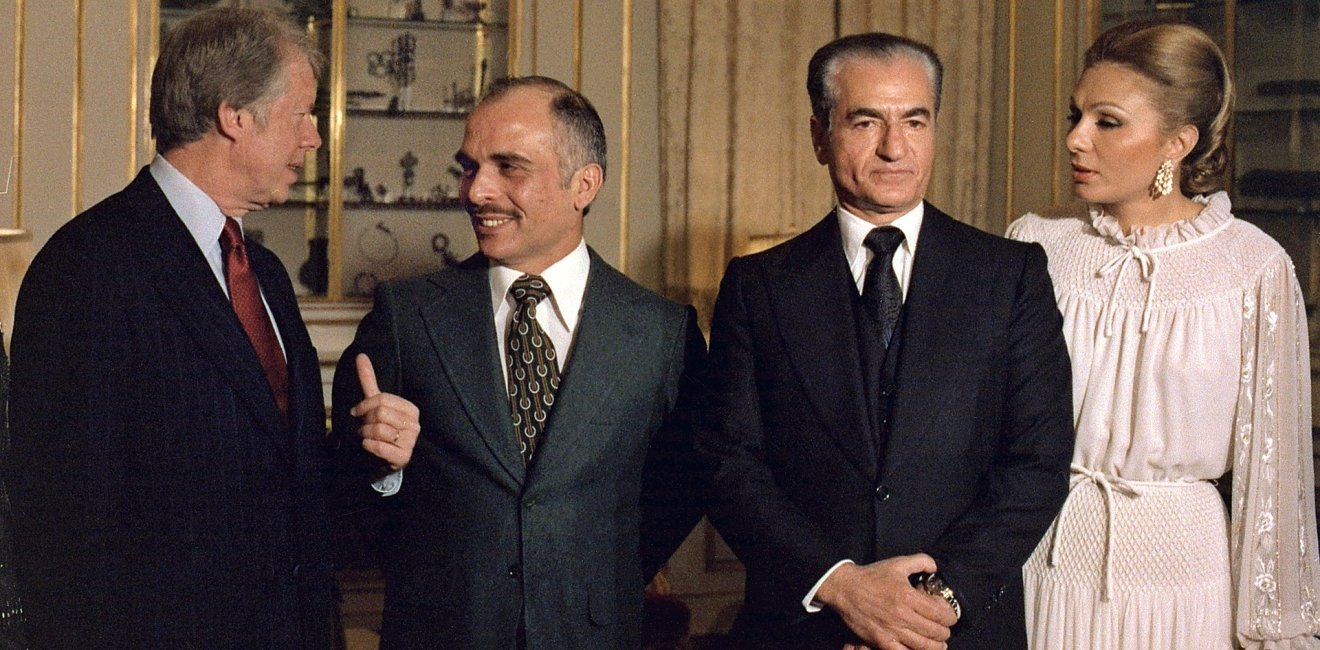

That same year, following the crisis in Egypt, the US increased diplomatic support for Hussein. On June 17, 1957, Secretary of State John Dulles informed Egypt, "Nasser should be under no illusion regarding US determination that Jordan shall be left free to decide its own policies according to its own conception."[7] In a meeting between Eisenhower and Hussein on March 25, 1959, during Hussein's first trip to the United States, the president expressed his fears of Soviet imperialism in the region and pledged continued military and economic aid to Jordan.[8] Hussein's visit and his declared willingness to support American interests in the region began a partnership between the two countries that would last through eleven American administrations and the reigns of both Hussein and his son Abdullah II.

Once the Americans and the Jordanians established a working relationship, they continued to increase their mutual support. In future conflicts, like the 1973 Yom Kippur War the Americans aided the Jordanians while restraining the Israelis from destroying Hussein's forces. Jordan has since played a vital role in the American attempts to forge a peace between the Israelis and Palestinians, and became the second Arab country to sign a peace deal with Israel. King Hussein, despite failing health, worked tirelessly to bridge the divide between the Israelis and the Palestinians at the Wye River Agreement in 1998. Finally, Jordan under Hussein's son, Abdullah II, continued this relationship and supported the Americans during the second war with Iraq and the American efforts to defeat ISIS. While the relationship began because of the Cold War, it has grown into a mutually beneficial partnership that remains strong almost thirty years after the Cold War ended.

[1] http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/ct-us-airstrike-in-syria-20170520-story.html and https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/08/world/middleeast/us-trains-syrian-rebels-in-jordan-to-fight-isis.html

[2] https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1955-57v14/d136

[3] https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1955-57v14/d335

[4] King Hussein, Uneasy Lies the Head: The Autobiography of His Majesty King Hussein I of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan (New York: Bernard Geis Associates, 1962), 112.

[5] Hussein, Uneasy Lies the Head, 108-9.

[6] Hussein, Uneasy Lies the Head, 159.

[7] https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1955-57v17/d340

[8] https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1958-60v11/d397

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more