Liang Sicheng as CIA Defection Target in Mexico City: New Evidence from the JFK Files

Adam Cathcart examines evidence from the JFK Assassination Records concerning CIA efforts to prompt Chinese architect Liang Sicheng to defect to the United States.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Adam Cathcart examines evidence from the JFK Assassination Records concerning CIA efforts to prompt Chinese architect Liang Sicheng to defect to the United States.

In December 2022, the United States government released over 13,000 documents categorized as JFK Assassination Records. Some of these previously classified documents dealt with Cuba and Mexico, given that these were places where both Lee Harvey Oswald and US intelligence officers had been active in the early 1960s.

Two newly released JFK documents focused on in this essay center on US Central Intelligence Agency interest in documenting and leveraging internal dissent amongst artistic intelligentsia in the People’s Republic of China, and the CIA’s related drive to get Chinese officials to defect to the West. In the early 1960s, the Agency was collecting “case studies of disaffection” among “Chinese Communists stationed abroad or sent out on tours with delegations,” and were alert to the increase in what one internal study called “opportunities to stimulate defections.”[1]

In 1963, the CIA was monitoring architect Liang Sicheng, exploring the potential for a defection during his trip to Mexico City that autumn. Liang is today a very famous figure among Chinese artists and architects as well as foreign art collectors and urban planners, celebrated as a patriotic intellectual who combined sensitivity to traditional Chinese architecture with foreign modernism.[2] He had studied at the University of Pennsylvania in the late 1920s and had interactions with Mao Zedong in the early 1950s, when the Chinese Communist Party was bulldozing all sorts of ancient walls, gates, and towers – to Liang's disappointment and probably real depression. However, he and his wife stayed in China and worked with the CCP in the end, jointly designing the Monument to the People’s Heroes in Tiananmen Square.[3]

In 1963, Liang was part of a PRC delegation at an international architecture congress which took place partly in Havana and partly in Mexico City operating within a “mediating niche” in the Cold War.[4] At this congress, Liang would have heard speeches by Che Guevara and seen Fidel Castro, and rubbed shoulders with other socialist planners.[5] The US government tried to prevent the congress from happening at all, with George Bundy menacing the planners and the State Department also intervening, pressing for Havana to be dropped altogether.[6]

Beyond this polarizing backdrop, had Liang defected, it would have been a major embarrassment to the conference hosts, netting the US government one of its highest-level defections from the PRC and potentially providing the Central Intelligence Agency with more specific fodder about the state of affairs close to the apex of cultural and political power in Beijing.

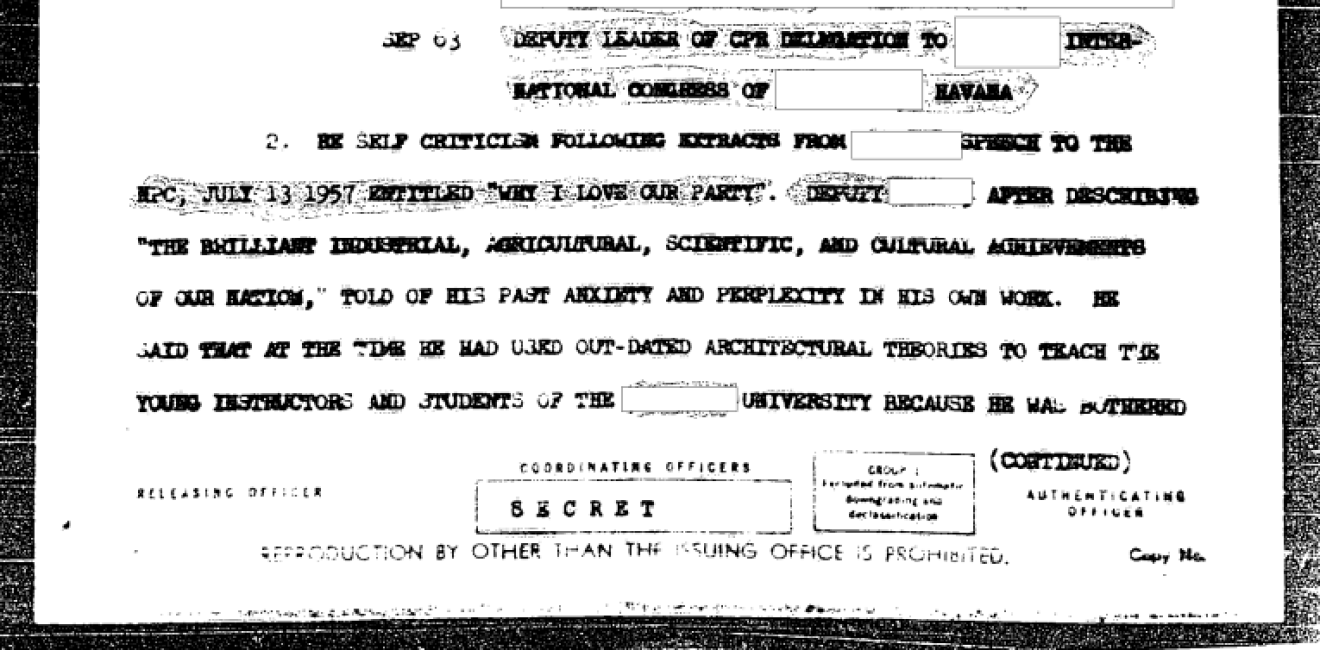

Playing a significant role in why they thought he would be a good target for defection were two factors: the CIA was in control of Liang’s brother in the US and using him to arrange a meeting between the two men in Mexico City in which defection would be raised as a real possibility. Secondly, the Agency had a copy of Liang's self-criticism which he delivered as a speech before the National People's Congress in the summer of 1957 (it had been published in the People's Daily on July 14 of that year), some of which is translated in one of the CIA files released as part of the JFK Assassination Records.[7] Liang's line about being child-like in hatred and anger at the mother party was directly picked up on by Edward Hunter in his 1958 Black Book on Chinese Communism.[8] The language seems therefore to have circulated widely amongst the US intelligence community and its supported anti-communist authors; it makes an appearance in this letter from the CIA Director to Mexico City.

Oddly, although Liang is from a very famous family, there is no record whatsoever of a brother along the lines of the one described – that is, a person who was living and working for the US government National Geological Survey, based in Washington, with a family in Riverton, an industrial neighborhood in south Seattle. Yet, according to the CIA, Liang Sicheng was sending quite descriptive letters to his brother in Seattle (the file goes into some detail) although they had not seen one another in “thirty years.”

Finally, the CIA document describes trying to set up a meeting in Mexico City: “While the brother is willing to introduce the subject to a KUBARK officer we have no guarantee the brother would buy this.” Kubark is an intelligence lingo for the CIA itself.[9] Liang never defected, and no open records exist to indicate that he was ever presented with such an option. Nevertheless the interest which US intelligence officials demonstrated in Liang Sicheng’s self-criticism, his biography, his correspondents, and his travels was indicative of the double-edged dangers and opportunities for both the US and China within the fraught terrain of “people to people” interactions of the Cold War.

[1] For more context on the CIA view of defections from Chinese embassies, see Henry Flooks, “Chinese Defections Overseas,” Studies in Intelligence, Issue 9, 1965 https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000609021.pdf

[2] Wilma Fairbank, Liang and Lin: Partners in Exploring China's Architectural Past (Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994); Daniel Slotnik, “Lin Huiyin and Liang Sicheng, Chroniclers of Chinese Architecture,”

New York Times, May 14, 2018, A19.

[3] Harold Kalman, “Chinese Spirit in Modern Strength: Liang Sicheng, Li Huiyin, and Early Modernist Architecture in China,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 58 (2018), 154-188.

[4] Miles Glendenning, ‘Cold-War Conciliation: International Architectural Congresses in the late 1950s and early 1960s,” The Journal of Architecture Vol. 21, no. 4 (2016), 630-650; Miles Glendinning, "The Architect as Cold-War Mediator: THE 1963 UIA Congress, Havana," Docomomo Journal, No. 37 (September 2007) pp. 30-35. 47-20-PB.pdf

[5] Peter Speakman, “International Union of Architects Congress, Havana Cuba and Mexico City 1963,” film footage, National Library of Scotland, Moving Image Archive, http://movingimage.nls.uk/film/9928

[6] Glendenning, “Cold-War Conciliation,” pp. 208-210.

[7] Liang Sicheng, “我为什么这样爱我们的党?[Wo weishenme zheyang ai women de dang? / Why do I love our Party?], Renmin Ribao, July 14, 1957.

[8] Edward Hunter, The Black Book on Chinese Communism: The Continuing Revolt (New York: Friends of Free China Association, 1958), 28.

[9] Tim Weiner, “The Spy Agency’s Many Mean Ways to Loosen Cold-War Tongues,” New York Times, February 9, 1997, p. 7; Weiner excerpts a 1963 CIA document entitled “KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation,” which, according to Dujmovic, was obtained by the Baltimore Sun through a FOIA request in 1997. See Nicholas Dujmovic, “CIA and Interrogations: Today’s Debate and the Historical Discussion,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 55, no 1 (March 2011) p. 62, footnote 28.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more