Mexican Leadership in Addressing Nuclear Risks, 1962-1968

Mexican diplomats were active promoters of nuclear arms control and nonproliferation after the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, writes J. Luis Rodriguez.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Mexican diplomats were active promoters of nuclear arms control and nonproliferation after the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, writes J. Luis Rodriguez.

Since the late 1950s, the United States and the Soviet Union attempted to build constraints on nuclear arsenals to prevent catastrophes. The prospects of nuclear Armageddon during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 gave their efforts a renewed urgency. As the international community joined the Cold War superpowers in their quest to build political tools to guarantee security from nuclear weapons, Mexican policymakers proved crucial in findings ways to address nuclear perils in Latin America as well as internationally.

The nuclear order-building efforts depended on US hegemony and relied on nuclear powers’ cooperation. The United States and the Soviet Union brought countries from the North American Treaty Organization and the Warsaw Pact to draft a nuclear nonproliferation treaty. After this group of ten governments could not reach a consensus, US and Soviet leaders formed the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament (ENCD) by inviting four neutral and four non-aligned nations to the negotiating table. Mexico was one of the neutral countries invited to this Committee.

The United States considered that the countries in the ENCD, most of them its allies, would accept its preferences, while the Soviet Union thought it would have a favorable audience among the nations of the Global South. Mexican diplomats were crucial in forging consensus among the eighteen delegations, balancing competing goals around nuclear technologies, and gathering support for the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) when it opened for signatures in 1968.

Mexican diplomats were especially active promoters of nuclear arms control and nonproliferation after the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis for three main reasons. First, the possibility of a nuclear confrontation in the Caribbean made the Mexican government aware of Mexico’s vulnerability in the event of a nuclear conflict between the superpowers.[1] For instance, Soviet strategies targeted various Mexican border and inner cities to block assistance going into the United States in case of a nuclear war.[2] Second, the crisis created common interests and cooperation between the two superpowers, nuclear-weapon states, and non-nuclear-weapon states. Third, the idea of mutually assured destruction permeated US and Soviet thinking, producing a fertile camp for nuclear governance demands. These three elements created a propitious context. Mexican representatives framed their efforts as not only attempts to guarantee Mexican security but actions addressing shared regional and international anxieties.

As the ENCD negotiated the NPT, Mexican diplomats led a Latin American effort to create the first nuclear-weapon-free zone (NWFZ) in a densely populated area. The regional talks took place in the Tlatelolco neighborhood in Mexico City from March 1965 to January 1967. The Treaty of Tlatelolco and the NPT promoted different compromises among advocates of disarmament, nonproliferation, and peaceful use of atomic energy. Mexican diplomats used the Treaty of Tlatelolco and mobilized Latin American countries to increase their leverage during the negotiations drafting the NPT.[3]

Documents from the Archivo Histórico Genaro Estrada, part of the Acervo Histórico Diplomático at the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs, illuminate how Mexican policymakers attempted to address regional and international nuclear risks simultaneously. Below I share descriptions of several key documents. The notation I use cites the book number in Roman numbers, followed by the folio and annex numbers. The documents have also been republished on the Wilson Center Digital Archive.

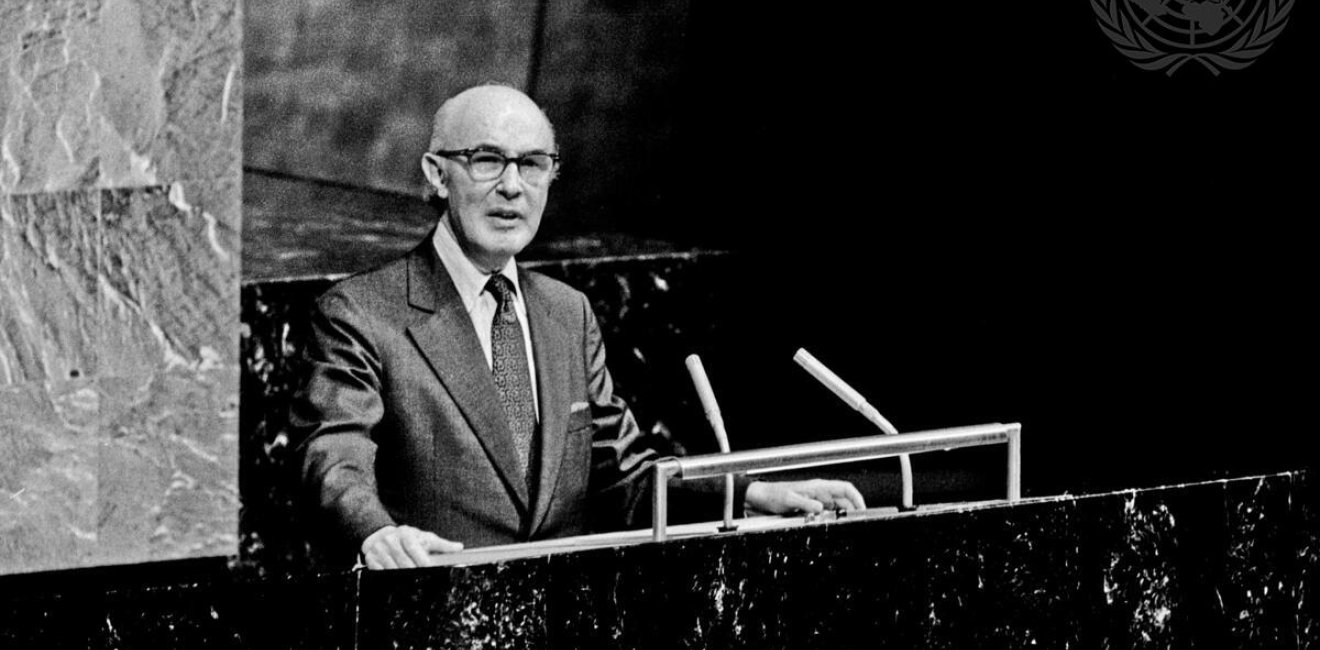

The president of the Mexican delegation to the United Nations (UN), Ambassador Alfonso Garcia Robles, explained why the Latin American nuclear-weapon-free zone (NWFZ) would represent the most ambitious regional project to address nuclear perils. He explained the security implications of the agreement, especially in terms of nuclear nonproliferation, nuclear disarmament, and negative security assurances. He also clarified that the Latin American project would benefit signatories economically. He argued that Latin American governments would not have to waste the resources necessary to engage in nuclear arms races if the region were denuclearized. Moreover, he explained that Mexico’s final aim was to achieve general and complete disarmament; thus, Mexican authorities saw the NPT as a means and not a goal on its own.

Alfonso Garcia Robles used his address to describe the progress in the negotiations of the Treaty of Tlatelolco. For him, this treaty included the most ambitious definition of nuclear weapons compared to existing nuclear governance texts. Another innovation was the reliance on the International Atomic Energy Agency’s safeguard system to monitor compliance. Garcia Robles also explained that Latin American delegations were almost in consensus about the Treaty of Tlatelolco text except for a couple of issues. Countries did not agree on defining the territory where the treaty would apply and when it would enter into force. The Ambassador also took this opportunity to explain the Latin American efforts to obtain negative security assurances from China. Moreover, he reminded delegates that the success of the NPT would depend on balancing obligations for nuclear and non-nuclear-weapon states. Mexican representatives argued that it was necessary to include more ambitious disarmament goals in the draft of the NPT. However, they rejected proposals to condition the approval of the NPT on the existence of concrete steps toward disarmament.

Alfonso Garcia Robles announced the success of the negotiations drafting the Treaty of Tlatelolco and its opening for signatures. He recounted the expressions of support and admiration for the treaty from different authorities, especially from U Thant, the UN Secretary-General, who hoped the Treaty of Tlatelolco would serve as an example and an impetus for similar efforts. He also explained that the Treaty of Tlatelolco managed to balance two fundamental goals: preventing the proliferation of nuclear arsenals and guaranteeing access to peaceful uses of nuclear technologies.

“Memorandum para acuerdo presidencial.” XXII-188-33, April 19, 1968.

The memorandum explains the directions that the Mexican president gave to the Mexican delegation. The president’s instructions were to modify the text of the NPT in order to increase support for the treaty, act as a bridge among dissenting opinions in Latin America, and prevent disruptions to the Treaty of Tlatelolco.

This memorandum is a compendium of comments about the Treaty of Tlatelolco made by different delegations at the UN. It includes statements by the delegates from the United States, Brazil, Ireland, Ethiopia, Austria, Italy, Pakistan, El Salvador, Mauritania, Iraq, Greece, Spain, Tanzania, Zambia, the Netherlands, Argentina, Venezuela, Sierra Leone, Canada, Jordan, Ecuador, Guyana, Colombia, Malta, Panama, Bolivia, Costa Rica, and Peru, in that order.

Alfonso Garcia Robles explained Mexico’s position toward the proliferation of nuclear weapons, the Mexican delegation’s position toward the NPT draft, and a comparison between the Treaty of Tlatelolco and the NPT draft. He explained that the Mexican delegation favored the NPT draft but wanted to make minor language modifications and include an explicit reference to the UN Charter’s articles on the use of force, especially Articles 2 (IV) and 26. Garcia Robles also explained why he thought the Treaty of Tlatelolco was “superior” to the NPT draft as a response to nuclear risks. He argued that the regional treaty better addressed nuclear threats than the NPT draft because it included more constraints on nuclear powers, a more precise definition of a nuclear weapon, and a more institutionalized system of controls.

Alfonso Garcia Robles explained how the Mexican delegation tried to gather the support of the Latin American countries for the NPT draft. These countries prepared and presented modifications to the NPT text, and the United States and the Soviet Union accepted some of these proposals. Garcia Robles reported that the Argentinian and Brazilian representatives said they recognized the value of the NPT but would not support it if it kept its clause prohibiting peaceful nuclear explosions. The Ambassador also reported the Soviet positive reactions toward the Treaty of Tlatelolco. Garcia Robles recounted the skepticism of some delegations toward the NPT. He recommended not to sign the NPT in 1968 unless the Soviet Union signed Protocol II of the Treaty of Tlatelolco, which includes negative security assurances.

This blog post forms part of a project on the constitutional history of the NPT funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

[1] Arturo C. Sotomayor, “Brazil and Mexico in the Nonproliferation Regime: Common Structures and Divergent Trajectories in Latin America,” The Nonproliferation Review, vol. 20, no. 1, 2013, pp. 81–105.

[2] Alejandro Nadal, “Trayectorias de misiles balísticos internacionales: implicaciones para los vecinos de las superpotencias,” Foro Internacional, vol. 30, no. 1, 1989, pp. 93–114.

[3] Mónica Serrano, Common security in Latin America: the 1967 Treaty of Tlatelolco, London, Institute of Latin American Studies, 1992. Jonathan Hunt, “Mexican Nuclear Diplomacy, the Latin American Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone, & the NPT Grand Bargain, 1962-1968,” in Negotiating the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: The Making of a Nuclear Order, ed. Andreas Wenger, Roland Popp, and Liviu Horovitz (New York: Routledge, 2017).

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more