Introduction

GRU Lt. Colonel Pyotr Popov is considered to be the CIA’s first Soviet double agent. There are numerous books that discuss his espionage activities. To name just a few: William Hood, Mole: The True Story of the First Russian Intelligence Officer Recruited by the CIA (1982, 1993); Tom Mangold, Cold Warrior: James Jesus Angleton, The CIA’s Master Spy Hunter (1991); David Wise, Molehunt: The Secret Search for Traitors That Shattered the CIA (1992); David E. Murphy, Sergei A. Kondrashev, and George Bailey, Battleground Berlin: CIA v. KGB in the Cold War (1997); John Limond Hart, The CIA’s Russians (2003); Clarence Ashley, CIA Spymaster: George Kisevalter, the Agency’s Top Case Officer Who Handled Penkovsky and Popov (2004); and Tennent H. Bagley, Spy Wars: Moles, Mysteries, and Deadly Games (2007).

Battleground Berlin by Murphy, Kondrashev, and Bailey offers the most extensive account of Popov’s case from the Soviet perspective. One of the co-authors, Lt. General Sergei A. Kondrashev (1923-2007), a high-ranking veteran of the First Chief Directorate of the KGB (foreign intelligence), interviewed Maj. General Valentin V. Zvezdenkov (1920-1997) who had a long and distinguished career in the Second Chief Directorate of the KGB (counterintelligence). The interviews took place in Moscow in November 1996 (Battleground Berlin, p. 487, fn. 3).

Zvezdenkov’s involvement with Popov was first mentioned by Popov himself in the so-called “cylindrical letter” he passed to CIA case officer Russell Langelle in the men’s room of Moscow’s Aragvi Restaurant on September 18, 1959 (Battleground Berlin, pp. 279-280). Zvezdenkov confirmed to Kondrashev that he had investigated Popov while the latter was based at the GRU Strategic Intelligence Operational Group in Karlshorst, Germany. He also confirmed that he was Popov’s main handler when Popov interacted with the CIA officers in Moscow. However, Zvezdenkov produced no material evidence to substantiate his claims.

Zvezdenkov’s later career took him to Vilnius, Lithuania, where he was appointed the principal deputy chairman of the KGB of the Lithuanian Socialist Soviet Republic in October 1978. He retired from this position in January 1987.

Because of Zvezdenkov’s service in Lithuania, I had a hunch that the documents related to his earlier professional career might also have been deposited in the KGB archive in Vilnius. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the files of the KGB archive came into the possession of the authorities of independent Lithuania. They are now curated by the Lithuanian Special Archives (LYA) in Vilnius and are available to researchers.

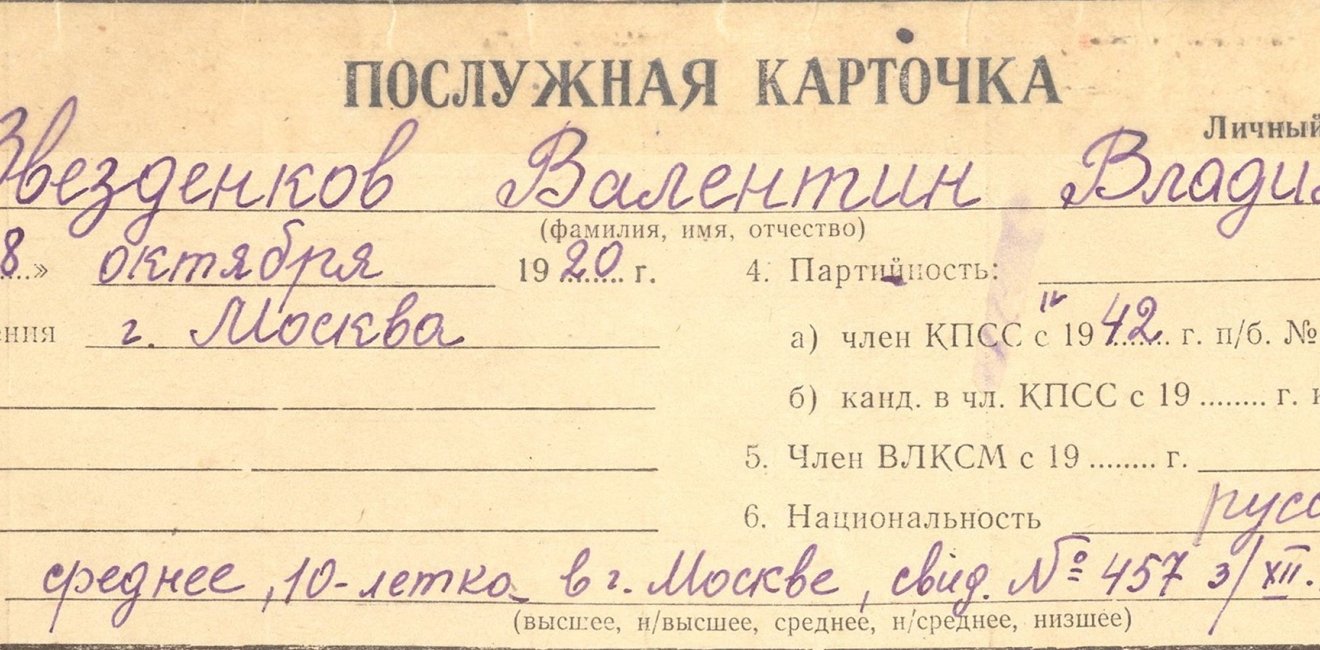

I contacted the LYA and was overjoyed but not surprised to hear that there is indeed a four-page document related to Zvezdenkov: his handwritten detailed professional biography (see Fond No. K-1, Inventory 61, Card No. 4810-4813), a file that offers much more precision and clarity on Zvezdenkov’s activities in Germany than what could be found in Battleground Berlin. More importantly, this file is also valuable to the Popov case, contesting, in one crucial aspect, the interpretation of events presented in the major published accounts of his case.

The Revelations

Zvezdenkov’s detailed professional biography shows that immediately prior to being sent to Germany in June 1954, he was the section chief of the 3rd Department of the 4th Directorate of the KGB. The focus of this Department was on the so-called Baltic “bourgeois nationalists,” a designation used by Soviet state security to describe those who opposed the Soviet political regime in the Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.

Considering the traditionally close economic and cultural links between the Baltic states and Germany, many of these individuals, including ethnic Germans, immigrated to Germany in the post-WWII period. Having been schooled in counterintelligence, Zvezdenkov was sent to “cultivate” (razrabotka) them, either to recruit them for the Soviet cause or, alternatively, to counteract and subvert their activities.

Zvezdenkov’s first major appointment – starting on August 2, 1954, after a 2-month period of acclimatization to the local conditions in Karlshorst, Germany – was that of the deputy chief of the 6th Department of the KGB Office (Apparat), also known as the Inspectorate on Security Questions Attached to the Supreme Soviet Commissioner.

The 6th Department targeted anti-Soviet immigrant activities in Germany and Zvezdenkov’s job was to strengthen and sharpen the focus on the Baltics. At this point, he was obviously quite removed from crossing paths with the GRU in general and Pyotr Popov in particular.

However, according to his biography, on April 18, 1955, Zvezdenkov was moved to another department. He became the deputy chief of the 8th Department. The focus of the 8th Department was the so-called “Soviet colony,” in other words, all Soviet civilian and military personnel based in Germany. Almost overnight, Zvezdenkov’s job changed from keeping an eye on dissidents from the Baltic diaspora to keeping an eye on potential dissidents among the Soviets themselves. It is only in this new position that somebody like Popov could come into Zvezdenkov’s field of vision.

The only existing publicly accessible source on Zvezdenkov’s professional activities in Germany is the website of the FSB-affiliated historian Oleg Mozokhin. However, for some reason, perhaps related to the KGB/FSB disinformation regarding the Popov case, Mozokhin excluded this particular appointment from Zvezdenkov’s biography. According to Mozokhin, Zvezdenkov was employed in the 6th Department until September 1, 1957. And yet, Mozokhin also claims that Zvezdenkov “cultivated” Popov in Berlin. This makes no sense. Had Zvezdenkov stayed in the 6th Department, he’d be cultivating immigrants from Lithuania, not GRU officers.

The 8th Department was a different story, however. According to his professional biography from the LYA document, Zvezdenkov spent more than two years as a deputy chief of the 8th Department with full access to the KGB surveillance and other clandestine ways of getting to know the true attitudes and behaviors of Soviet military officers and other Soviet citizens in Germany. His expertise on Soviet malcontents and potential traitors must have increased exponentially. The description given of him in Battleground Berlin as “an experienced counterintelligence officer” (p. 272) can therefore be assessed as accurate.

Then, in September 1957 (though not on September 1 as Mozokhin has it), Zvezdenkov was transferred to another position within the KGB in Germany. This new position made it possible for Zvezdenkov to interact with Popov on regular basis, enabled him to keep Popov under close surveillance and also potentially interfere in Popov’s professional activities. Based on the LYA document, it is possible to reveal publicly for the first time what that position was.

The KGB decree No. 00482 from September 2, 1957, made Zvezdenkov the new chief of the 7th Department (later renamed the 3rd Department and discussed under that designation in Battleground Berlin). The 7th Department was in charge of illegals, that is to say, Soviet agents without official cover who operated under false identity. Mozokhin makes no mention whatsoever of Zvezdenkov’s running this Department.

The illegals department position was a noteworthy promotion for Zvezdenkov. According to Battleground Berlin, “the Karlshorst émigré department [Zvezdenkov’s previous department] was a large, busy unit, but it was neither the largest nor the most vital in KGB. Honors for this role went to the illegals department of the Karlshorst Apparat, whose activities in East Germany supported Soviet illegals operations throughout the world” (p. 266). And Zvezdenkov was put in charge of it all.

At the same time, his GRU counterpart, the person handling the illegals on behalf of the GRU in Karlshorst, was none other than Lt. Colonel Popov. Popov had transferred to Karlshorst a few months earlier, in June 1957, and was already heavily involved in the illegals’ support when he began interacting with Zvezdenkov in September. The fact of such close institutional relations between Zvezdenkov and Popov has not been revealed until now.

Interestingly, just a month after Zvezdenkov’s transfer to head the illegals department, a controversial operation involving a female illegal agent Margarita Tairova took place. Tairova was dispatched to New York to meet with her pretend husband, another Soviet illegal, but they both quickly left the United States after allegedly noticing that they were followed by the FBI (Battleground Berlin, p. 274).

On the face of it, this operation looked like a clear intelligence failure for the Soviets. However, considering Zvezdenkov’s leadership position in the illegals department, could it not have been intentionally designed to compromise Popov? According to Battleground Berlin, this was not the case and the failed operation with Tairova did not seal Popov’s fate. Though the authors of Battleground Berlin admit that the suspicion of Popov was growing, they argue that the KGB was still not certain about his ties to the CIA because he was allowed to operate freely, to take vacations to the Soviet Union during the following year, and, upon his return, to continue meeting with his main CIA handler, George Kisevalter and one of Battleground Berlin’s co-authors, David Murphy.

On the other hand, the transfer of a seasoned counterintelligence officer, such as Zvezdenkov, to be in charge of the illegals department just a few months after Popov’s arrival – the fact that, for different reasons, both the authors of Battleground Berlin and the FSB historian Mozokhin fail to mention – seems to indicate that the KGB counterintelligence had closed the circle around Popov by the summer of 1957.

Then, about a year after the Tairova incident in November 1958, there was a sudden change of pace. According to Battleground Berlin, Popov requested an emergency meeting with his CIA handlers on November 8. The meeting was scheduled for November 24. The time period in between the two dates is described as “perfectly normal… [Popov] was even made duty officer for the night of November 15-16, a job that gave him access to all of the unit’s files,” (p. 276). The next morning, however, Popov received a cable to return to Moscow to report in person on the case of an American student he had recruited (with the assistance of the CIA).

What was not known to the CIA officers then but is known now thanks to the document from the LYA, is that by this time in mid-November, Zvezdenkov had already left Germany. His appointment as the head of the illegals department officially ended on November 12, five days before Popov was recalled to Moscow.

In other words, when Popov met his CIA handlers in Germany for the last time on November 24, the work of the KGB counterintelligence regarding his case was already wrapped up. He was now, beyond any reasonable doubt, a doomed man and he should have been strongly dissuaded from returning to Moscow by his handlers.

To re-state the point, the timing of Zvezdenkov’s departure from Germany noted in the LYA document seems to indicate – and, understandably, this may come as a surprise to some - that Popov’s ties to the CIA were firmly established by the KGB counterintelligence before Popov’s return to Moscow. The existing major accounts of the Popov case which trace his exposure to the bungled activities of his CIA handlers in Moscow appear conclusively invalidated by this finding.

The LYA document offers another indication that Zvezdenkov was intentionally transferred to Moscow to continue running the Popov case against the CIA. It includes the mention of the KGB decree No. 549 from December 25, 1958, which made him the deputy chief of the 2nd Section of the 1st Department of the Second Chief Directorate, with the starting date on December 17. According to Battleground Berlin, “on December 17, Popov’s wife processed baggage for return to the USSR,” (p. 277).

What was Zvezdenkov’s main responsibility in his new job? Running counterintelligence deception operations against the United States. In other words, instead of re-connecting with Popov in Moscow, the CIA should have stayed away from him.