Postal Intelligence

For American analysts, spies, satellites, secret codes, and, yes, postage stamps offered clues about the hidden intentions and policies of Soviet bloc countries.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

For American analysts, spies, satellites, secret codes, and, yes, postage stamps offered clues about the hidden intentions and policies of Soviet bloc countries.

Spies, satellites, and secret codes were not the only ways the United States tried to gather information on the hidden intentions and policies of Soviet bloc countries. The US also took advantage of something much more commonplace, something not typically associated with foreign intelligence or international relations: postage stamps.

Stamps—because of their ability to reach both ordinary citizens as well as a worldwide community of collectors—were sometimes used by governments to spread political messages.[1] During the Cold War, the CIA and State Department analyzed the designs on stamps issued by Soviet bloc countries in order to gain further insight into politics and global affairs.

An example of this was a CIA intelligence report from April 12, 1954, titled “Belief That Communists Are Using Von Schill Postage Stamp in Propaganda Effort to Foster German Nationalistic Feeling Against France.” It examined the possible motivations behind an East German stamp featuring Ferdinand von Schill, a Prussian soldier who had led an uprising against Napoleon’s forces in the early nineteenth century.

The report began, “I was astonished to see this particular design—and I believe it is highly significant in evaluating present political tactics by the Communist regime.” It highlighted how the issuance of the stamp coincided with the public debate in France over whether to join the European Defence Community, which called for the re-arming of West Germany. It accurately predicted that fears of resurgent German nationalism could lead to France not joining.

“East German Postage Stamps Honor Rote Kapelle Agents” was the title of another CIA memo from June 1, 1967. “Red Orchestra” referred to an anti-Nazi resistance movement during World War II. The memo noted that some members had relatives or associates living in the US, and therefore, a copy of the memo should be sent to the FBI for counterintelligence purposes.

Some stamps issued by Soviet bloc countries were discussed at the highest levels of the US government. The top-secret intelligence report prepared for the US president each morning, now known as the President’s Daily Brief, informed JFK about some important developments in the world of stamps on the morning of January 18, 1963:

The Hungarians have issued a series of stamps honoring Soviet and US astronauts, but quickly withdrew from circulation the one honoring [the second American to orbit the Earth, Scott] Carpenter. It seems he was put on the one with the highest denomination, which was taken to imply US superiority. Hungarian philatelists are having a field day.

In the end, it looks as though the astronauts were depicted in the order in which they traveled to space.

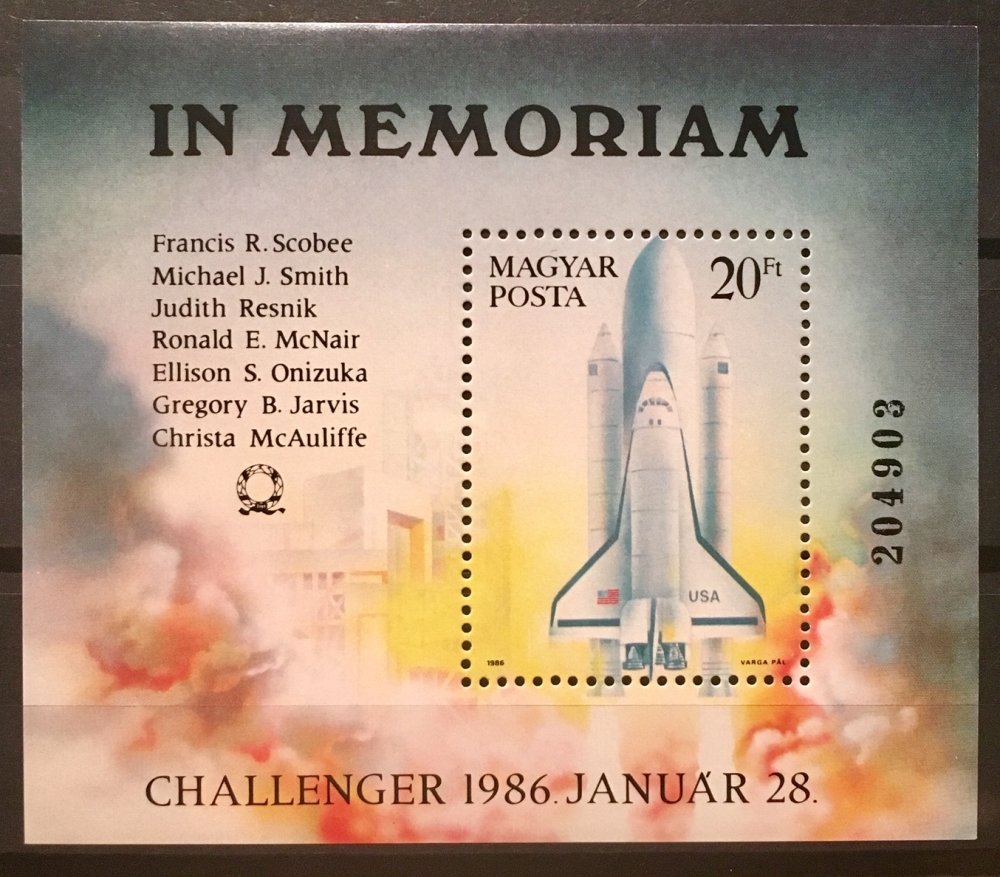

After Hungary issued a stamp commemorating the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, the US ambassador in Budapest wrote a letter to CIA Director Bill Casey on March 10, 1986, highlighting the significance of this stamp: “As far as I know this gesture is unique within Eastern Europe and was certainly an act which crossed ideological barriers.”

The State Department was also interested in how the designs on stamps could be useful for diplomacy. An airgram sent by the US Embassy in Kigali on May 18, 1965, titled “Pro-West Policy of GOR [Government of Rwanda] Indicated in Postage Stamps” observed:

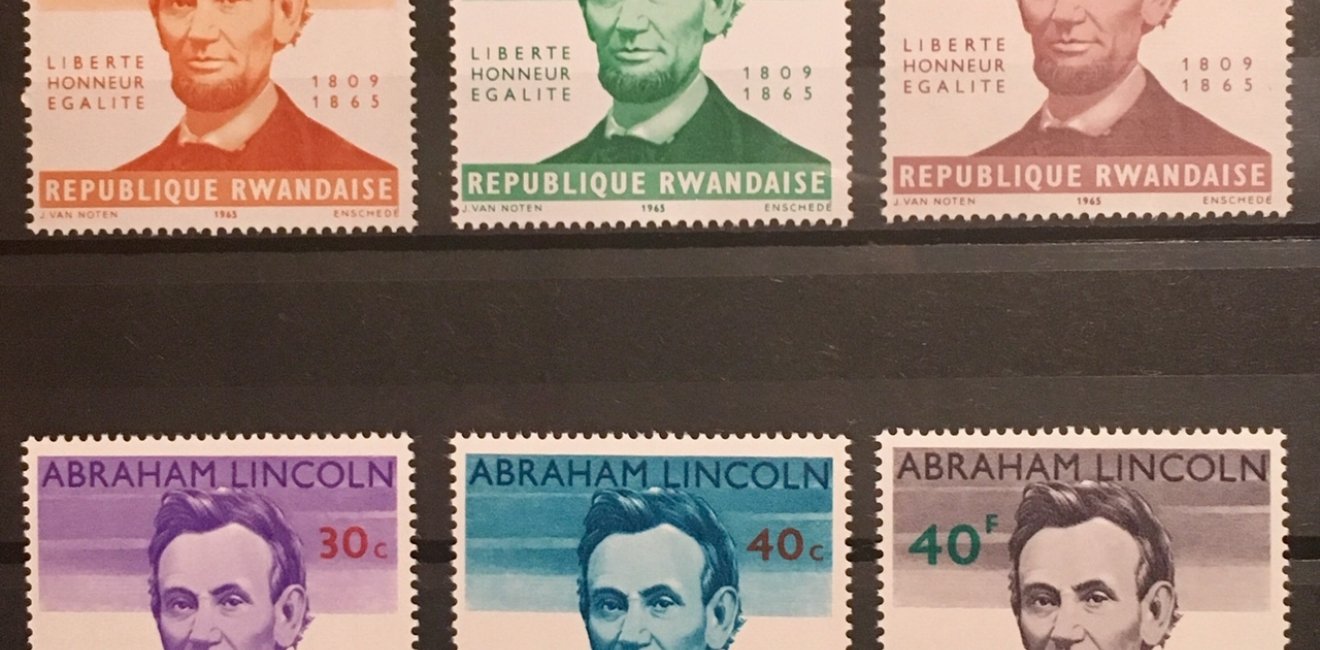

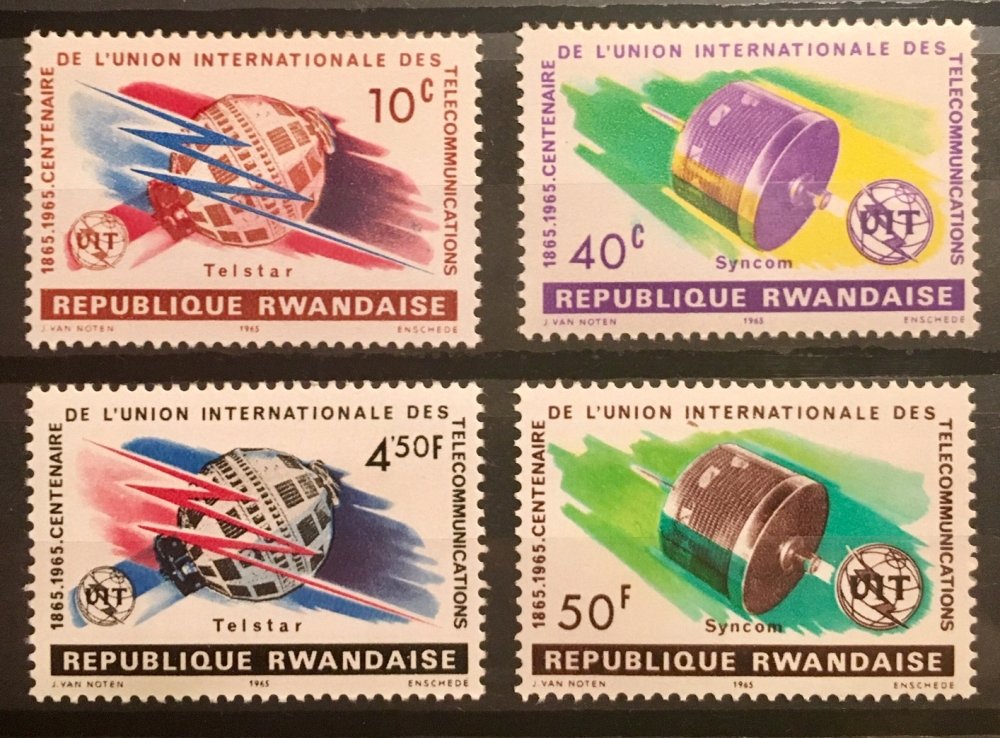

The Embassy has been struck recently by the number of American themes on Rwandan postage stamps issued recently. A few weeks ago a series of stamps in five denominations was issued on the 100th Centennial of the death of Abraham Lincoln. This week a series on [US communications satellites] “Telstar” and “Syncom” have appeared, in two denominations each.[2]

Much more than just carrying mail, stamps allowed governments to reach a global audience. However, in addition to collectors who appreciated the colorful designs on stamps, the CIA and State Department also recognized that stamps could provide a unique perspective on international affairs.

In the age of online propaganda, this small piece of Cold War history serves as a reminder of the power of visual communication, and the enduring value of open-source intelligence analysis.

[1] As I wrote in my paper in the Journal of Cold War Studies, the US also used stamps to promote its foreign policy goals. For example, the second most-printed stamp in US history was a 1952 stamp featuring NATO.

[2] Folder No. 05-05-25, Third Assistant Postmaster General Files, Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum Library, Washington, DC.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more