Riding the Washington Metro one morning I entered a car completely transmogrified into a rolling advertisement for the most recent production of the international entertainment conglomerate Cirque du Soleil. Washington seems to be surrounded by Cirque du Soleil these days. As the ceiling of my metro car proclaimed, Kurios opens later this month under a big tent at suburban Tysons Corner, Virginia. Meanwhile, a constant barrage of email notices have informed me that I wasn’t quick enough to catch Toruk, which just closed in nearby Baltimore; or Amaluna, which ran at National Harbor in suburban Maryland last year. As nearly everywhere these days, it seems, Washington area audiences can’t get enough of the nouvelle cirque from Montreal.

The Cirque du Soleil story is about far more than acrobatics under a large tent. Indeed, it highlights how particular urban micro-climates unleash powerful chemical reactions of creativity and place. Cirque du Soleil probably would never have taken shape anywhere other than in Quebec of the 1980s.

Two street performers – a juggler and a fire eater – applied for a provincial grant in 1984 to take their little troop Les Echassiers (The Waders) on a summer tour of Quebec to celebrate the 450th anniversary of Jacques Cartier’s voyage to Canada. Guy Lailberté and Gilles St-Croix founded their company in tiny Baie Saint Paul a few years before, and survived by winning a Canada Council for the Arts award in 1983.

With a new government grant in their pockets, they hired Guy Caron from the recently established École nationale de cirque de Montréal and consolidated their group under the title Les Grand Tour du Cirque du Soleil. Their small assembly would grow into the largest and most successful among Quebec’s nouveaux cirques, constantly responding to the rapidly changing political and cultural environment surrounding its origins. Within two decades, their troupe became the largest entertainment company in the world, earning 85 percent of its peak revenues in 2012 from the United States (largely from eight permanent productions in Las Vegas), while spending 85 percent of its operating budget in Quebec. The initial public investment by Quebec taxpayers has paid off enormous dividends for Quebec and Montreal.

Montreal -- with its vibrant tradition of street culture; absence of established circus ensembles; strong related cultural sectors such as dance, theatre, music; and willingness to invest public funds into the arts – shaped what Cirque du Soleil could and would become. As a band of street performers working in a durable local tradition, there was no place for animals to wander around as they moved through the province. Laiberté, who had supported a trip to Europe by performing as a folk musician and busker before becoming a fire eater, understood the power of music for driving a performance forward as did many popular Québécois musicians of the period. Quebec’s fractured linguistic atlas encouraged the performers to develop their own distinctive language of gibberish.

Caron, meanwhile, brought Franco Dragone on board. Dragone, from Belgium, was well trained in commedia dell’arte performance which aligned with the company’s emerging artistic sensibilities. More generally, the company’s approach fit into an incipient Montreal brand of circus performance that blended French nouveau cirque, Soviet acrobatics, and American entrepreneurship.

Lailberté and St-Croix returned from their initial tour of Quebec with empty bank accounts and reapplied for Canadian and Quebec support. The Province’s grantmakers and cultural bureaucrats remained skeptical of their success. In the end, the duo secured an all-important funding renewal upon the direct intervention of Quebec Premier René Lévesque, whose Parti Québécois government was busily promoting separation from Canada. The new money allowed the crew to take their show on the road outside Quebec for the first time.

While traveling around Canada, Lailberté and St-Croix caught the attention of the organizers of the Los Angeles Arts Festival, who invited them to perform at their 1987 showcase. By this time Lailberté and St-Croix managed to convince Mouvement des caisses Desjardins (Dejardins Group Credit Union) to cover more than $200,000 in bounced checks. They decided to give Los Angeles a try. California audiences fell in love with the company, as did executives from Columbia Pictures, which offered to finance a grand North American tour. Cirque du Soleil would open a permanent outpost in Las Vegas three years later.

The support of American funders enabled Cirque du Soleil to continue to grow by leaps and bounds as they established a major presence in many entertainment centers around the globe. At the same time, the company never lost its attachment to its birthplace in Quebec. The corporation put down deep roots in Montreal, building a massive headquarters and training center in the underprivileged immigrant portal neighborhood of St. Michel. Their investment established Montreal as a major focal point of the global circus world, luring top performers and ambitious amateurs alike. Their base has remained firmly rooted in Montreal, even after company was bought out by Chinese and American financiers.

Cirque du Soleil’s influence on Montreal in return extends beyond mere presence. As home to so much circus talent, Montreal spawned a vibrant extended circus community including gifted offshoots such as Les 7 doigts de la main (7 Fingers), Cirque Éloze, and Cirque Alfonse. These alternative companies are not mere imitations of Cirque du Soleil. The internationally successfully Les 7 doigts de la main, for example, has maintained a distinctive aesthetic featuring more human-scale performance styles. Les 7 doigts de la main also has worked closely with physical theater groups such as Gilles Maheu’s Carbone 14 and Robert Lepage’s groundbreaking Ex Machina, dance companies such as Édouard Lock’s La La La Human Steps as well as with musical groups such as Richard Ste-Marie’s La Fanfafonie.

The growth of Cirque du Soleil has been exceptional; even more so as it transpired at a time when the circus industry seemingly had entered a period of decline. Simultaneously, its success is a product of a larger trajectory within the Quebec performing arts community. In August 1948, a group of artists influenced by the French surrealists began to discuss the future of the arts in Quebec,publishing a manifesto proclaiming the “untamed need for liberation,” “resplendent anarchy,” and extoling the creative force of the subconscious. Mimeographed in four hundred copies, their platform sold for a dollar a piece at a local Montreal bookstore. The impact of their proclamation Le Refus Global (Total Refusal) proved enduring as commentators around Canada and abroad picked up their ideas for a “modern” Quebec culture.

The only dancer in the group, Françoise Sullivan, would become one of Canada’s best known abstract painters and sculptors as well as founder of a distinct tradition in modern dance. Four decades later, looking back on her career, Sullivan noted, “art can only flourish if it grows from problems which concern the age, and is always pushed in the direction of the unknown. Hence, the marvelous in it.” Cirque du Soleil has taken that Montreal sensibility to the world.

Author

Former Wilson Center Vice President for Programs (2014-2017); Director of the Comparative Urban Studies Program/Urban Sustainability Laboratory (1992-2017); Director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies (1989-2012) and Director of the Program on Global Sustainability and Resilience (2012-2014)

Urban Sustainability Laboratory

Since 1991, the Urban Sustainability Laboratory has advanced solutions to urban challenges—such as poverty, exclusion, insecurity, and environmental degradation—by promoting evidence-based research to support sustainable, equitable and peaceful cities. Read more

Explore More in Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Browse Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Hometown D.C.: America's Secret Music City

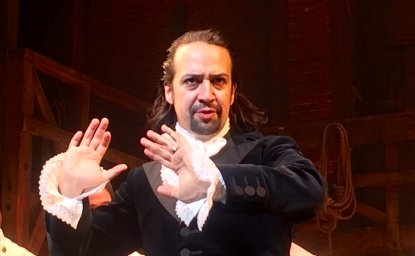

Bringing New York to the Broadway Stage

10 Steps to a More Genuine DC Experience