A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

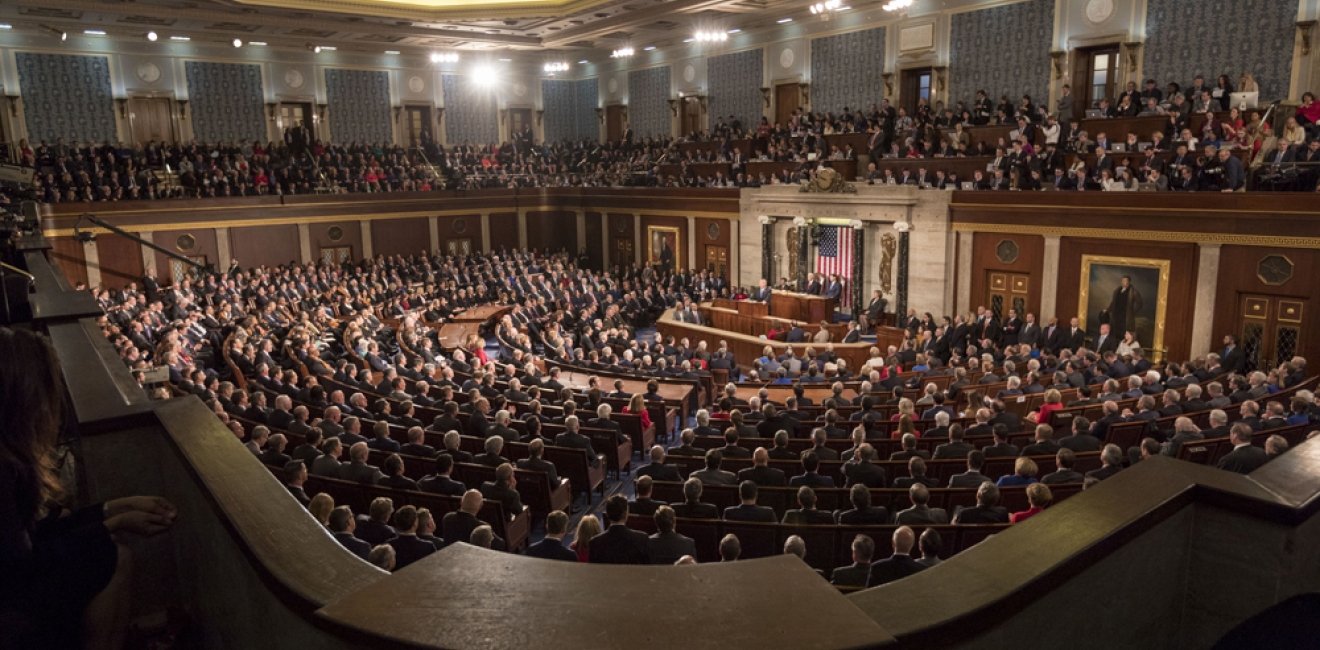

In his State of the Union address last month, President Trump declared that “the era of economic surrender is over.” That combative stance seemed an ominous beginning to outlining a protectionist U.S. trade stance. Surprisingly, though, he didn't mention any specific trade agreement by name, nor did he suggest ripping up existing ones. That’s still cold comfort at a time when anxieties about major disruptions in international trading patterns being one of the biggest risks to disrupt growth remain strong. The irony, though, is that much as what the administration wants in trade deals is exactly what other industrialized countries want as well.

The Trump administration’s singular focus on trade deficit remains unshaken. It remains resolute that seeing a marked decline in the U.S. goods deficit would be the one number in determining whether trade policy is a win or a loss. Never mind that the United States actually runs a trade surplus in goods and services with the rest of the world. At the same time, China is the source of nearly half of the U.S. trade deficit, and yet Washington’s priority is still to renegotiate trade deals that don’t involve Beijing, namely NAFTA and KORUS.

The good news for Canada, Mexico, and South Korea was that neither NAFTA nor KORUS was mentioned at the State of the Union speech. By being ignored, it was also spared from coming under attack at such a widely watched public forum. But in the battle to renegotiate trade deals, and not scrap them altogether, the way forward is actually to focus on the much larger picture of mutual interests.

By their nature, trade negotiations focus on specific sectors and the industries behind them. Certainly, the latest move by Washington to slap tariffs onto washing machines and solar panels is a classic move that is designed to protect domestic companies and interests. In an increasingly borderless global economy, though, such protectionist measures may actually hurt domestic consumers and businesses in the longer term.

Yet President Trump’s insistence on fair trade on a level playing field that reciprocates rules of business practices is something that all industrialized countries are clamoring for. In fact, one of the biggest needs to update existing trade rules would be to protect interests that have not been under consideration in trade deals until now, such as protecting intellectual property rights. The Trump administration has actually already begun taking the first steps to work together with like-minded countries to seek out common interests in the trade arena.

Late last year, the United States, European Union, and Japan joined forces to attack China’s practice of forced technology transfer, subsidizing state-owned enterprises, and excess production capacity that Beijing has made as critical to its economic growth. While not mentioning China by name, the three sides made a concerted effort to stand together, at the World Trade Organization no less.

Forced technology transfer in particular has been standard practice in China, and now countries including Japan, the EU, and the United States, are ready to fight back. So the Trump administration’s rallying cry for trade deals that are reciprocal, so that China would similarly have to give up its own technological know-how when they invest in other countries as it does to foreign corporations in China, should garner not just bipartisan support in the United States, but support worldwide. In fact, when President Trump said at the World Economic Forum in Davos last week that he might consider re-joining the TPP if the terms were favorable to the United States, he may well have considered the value of collective bargaining against China.

As the United States continues to weigh the advantages of NAFTA and KORUS, its focus should be less about reducing trade deficit numbers, especially in manufactured goods. Rather, negotiators should be more forward-looking in determining U.S. economic interests. The trade imbalance with China is undoubtedly distorted, but that can be leveled much more effectively by targeting Beijing’s unfair trade practices with like-minded countries and establishing rules that would punish distorting actions.

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2018, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

Author

Indo-Pacific Program

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more