A blog of the Kennan Institute

The last week of February 2024 marks the anniversary of two tragedies for Ukrainian society: the start of Russia’s occupation of Crimea, in 2014, and the launch of Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine, in 2022.

Ten years ago, in 2014, this terrible week included the massacre on the Maidan, the flight of disgraced President Yanukovych to Russia, the appointment of an interim president and government, Russia’s takeover of Crimea, and the start of the Russia-backed secessionist/irridentist movements in southeastern Ukraine.

Two years ago, this was the first week of the Russian full-scale invasion, marked by the bombing of cities and the precipitous departure of the first wave of refugees to Ukraine’s western regions and Europe. This week two years ago also saw the start of Ukraine’s ongoing resistance.

Both events—despite being separated by eight years—were part of a single historical process that has had a critical impact on the lives and security of the Ukrainian people. How are things with Ukrainians after ten years of Russia’s growing aggression? How do they see the current situation, and their own and the country’s future?

The Sociopolitical Context

In 2022, with the start of the Russian invasion, Ukrainian leadership and society entered into a specific state of public consciousness characterized by rallying around the flag, firm solidarity on the imperative of national resistance, and an outspoken faith in victory over the aggressor. Despite the existential threat, over 75 percent of the population expressed optimism about the state of affairs in Ukraine and the country’s future—an unusually high figure for Ukrainians (and for Eastern Europeans at large).

But with the passage of time, and as a result of military, demographic, and political challenges, society—and its opinion—began reverting to a more rational, sober state.

As happens in many societies at war, part of Ukraine’s population looked for a safer life abroad. According to most recent data, over six million refugees are currently in Europe, between 1.2 million and five million Ukrainians are in Russia (many of whom were deported unwillingly or are being kept in Russia by force), and more than 400,000 Ukrainians have migrated to Canada and the United States. As well, more than 3.5 million Ukrainians have moved from dangerous areas to resettle in safer regions in central and western Ukraine.

These migrations have radically changed the social structure and human geography of Ukraine. About a quarter of Ukraine’s former population has left the country, and an additional 10 percent have changed their place of residence within the country. Formerly large urban centers from Kharkiv to Odesa in southeastern Ukraine are now depopulated. The regions close to the front line are inhabited by elderly people who do not want to leave their homes and by military staff. Cities and towns in the central and western regions have gained some younger people. Also, Kyiv has witnessed waves of leaving and returning citizens. Today, Ukrainian society has fewer people, skews much older than before, and has adapted to life in a state of constant war and destruction.

Ukraine’s political class is adapting to the war as well. The sociopolitical role of military and security leaders and institutions has grown, as has trust in them. The conflict between President Zelensky and General Zaluzhny, as well as recent changes in the army’s leadership, exemplify two major political trends wrought by the ongoing war. First, the politicians and the generals have started competing with each other for the public’s trust, which can potentially evolve into a political struggle. Second, the civil government controls the generals. However, a Zaluzhny faction is taking shape in parliament—at least as far as can be discerned from voting patterns—and in wider society, suggesting leadership of the ex-commander.

Behind the fractious relations between Zelensky’s team and supporters of Zaluzhny, there is a deeper societal cleavage. As the public controversies over the draft law on mobilization demonstrate, Ukrainians are currently divided between those families whose members are in the army for two years with an unclear prospect of returning home and those families that don’t want to send their sons and brothers to fight. These two large factions are united in wanting victory over Russia but divided in their willingness to invest blood in achieving that victory.

Public Opinion of Ukraine’s Development and Leadership

In advance of the twin anniversaries, several polling organizations, including the Sociological Group “Rating” (Rating Group), the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), and the Razumkov Center, have published the results of surveys regarding what Ukrainians think about the current state of affairs in the country, the war, and the nation’s leadership.

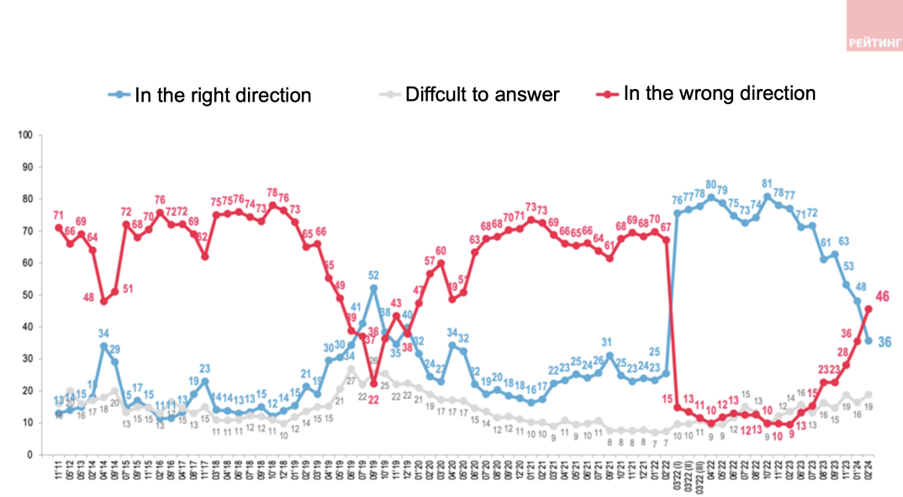

Probably the most important result is what can be called the sobering of Ukrainian society. Both KIIS and Rating Group polls demonstrate that pessimistic assessments of Ukraine’s development prevail again over the optimism of the first years of the war. Figure 1 shows the course of Ukrainian public opinion over the past ten years. Ukrainians’ inherent pessimism was challenged ten years ago by the Euromaidan, the annexation of Crimea, and the start of the Donbas war, all leading to a coalescing of a strong sense of nationhood and a desire to create and own the nation’s future. The optimistic sentiment increased with the electoral victory of Zelensky in 2019 and prospects of peace and nonoligarchic development. And for the next two years, levels of optimism remained high.

Figure 1. In your opinion, are things in Ukraine generally going in the right or wrong direction? (Rating Group)

The war of attrition has exhausted the populace’s optimism but not the will to victory, as the same poll showed. The proportion of citizens who are absolutely confident that Ukraine will be able to win a war with Russia is 42 percent, and another 43 percent are rather sure. The proportion with greatest confidence is smaller than in October 2022 (74 percent and 22 percent, respectively), but it also demonstrates that even a “soberer” society does not experience a decrement in the will to resist. A rational explanation for this new state of public opinion emerges from the widespread understanding that Ukraine’s victory is possible only if the West continues its support, an idea supported by 79 percent of respondents.

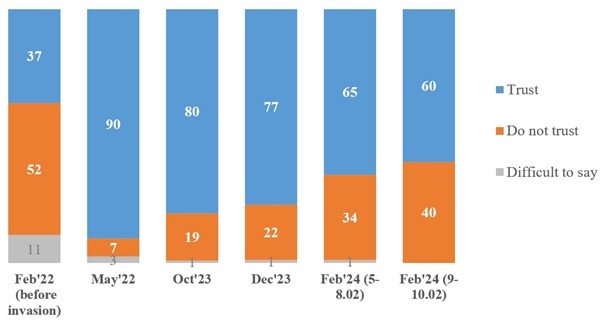

The public trust in the military and security leadership grows. According to the KIIS poll, the most trustworthy leader in Ukraine is Valeriy Zaluzhny, whose trust level stands at 94 percent (5 percent distrust) and has only grown in the recent three months. Public trust has also increased in Kyrylo Budanov (chief of Defense Intelligence, 66 percent trust versus 19 percent distrust) and Oleksandr Syrsky (since February 8 the new commander in chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, 40 percent versus 35 percent). Political leaders are also among the most trusted persons, but their trust level has declined: Volodymyr Zelensky enjoys the trust of 60 percent of respondents (with a 40 percent level of distrust; a thirteen percentage point drop in his trust rating in three months) and Serhiy Prytula is trusted by 61 percent (with 33 percent distrusting; an eight percentage point drop in trust rating in three months).

As figure 2 shows, the dispute between the president and Zaluzhny, and the dismissal of the popular commander without open explanation to the people, have cost Volodymyr Zelensky some public support as well as some bitterness among army personnel. (The last two columns in the figure show results of polls conducted on February 5–8 and 9–10, respectively.)

Figure 2. Dynamics of trust in Volodymyr Zelensky (KIIS, February 2022 –February 2024)

Despite changes in the ratings of individual leaders, public support for government remains high. As the Razumkov Center’s survey reveals, the Ukrainian government’s performance receives high ratings on restoring energy facilities to working condition after missile strikes (78.5 percent of respondents gave high marks for this), ensuring the proper functioning of communal utilities, transport, and availability of food supplies despite the war (78 percent), cooperating with Western partners (68 percent), helping refugees (63 percent), and ensuring the nation’s defense capability (62 percent). Mid-range marks are given to the government on fighting crime (45 percent) and helping vulnerable groups (44.5 percent). Ukrainians are dissatisfied with the government for being unable to sustain social justice (especially with respect to the draft regulations; 51 percent), a functional economy (46 percent), and restoration of the housing stock (40 percent).

Support and trust levels for different governmental institutions vary. Among the most trusted are the military and security organizations (from 68 to 95 percent), the institution of the presidency (64 percent), the police service (58 percent), and Ukraine’s National Bank (53 percent). But the public does not trust public officials (75 percent distrust), political parties (72 percent), the parliament (70 percent), the courts (68 percent), the cabinet (64 percent), and the anti-corruption organizations (51–52 percent).

Ten years of conflict with Russia have strongly affected Ukrainians. But despite all the shocks, challenges, and ills, Ukrainian society remains rational and keeps a critical eye on its leaders and its future. It sees problems, their causes, and possible solutions. And despite these tragic anniversaries, Ukrainians are still able to envision a bright future for themselves: today, 73 percent believe that in ten years’ time, Ukraine will be a peaceful and prosperous country once again.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute

Author

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in Focus Ukraine

Browse Focus Ukraine

Talking to the Dead to Heal the Living

Ukrainian Issue in Polish Elections