5/23/16

Nestled between Washington, D.C.’s lovely eighteenth century village of Georgetown and the ravine forming Rock Creek Park, Rose Park winds its way along a foot-and-bike path running between M and P Streets NW. Early mornings are given over to joggers and dog walkers; mid-afternoons to families; and later on, the baseball and tennis players join with shoppers at a popular weekly greenmarket. Some of the city’s most competitive street basketball games assume center stage pretty much any time in a basketball-mad town.

Rose Park is a gem; a pause in the hectic cityscape that would make any community proud. This bucolic patch is everything an urban park can be; a healing interval in an overly competitive town.

Rose Park is noteworthy not only for what is, but for what was. The Park was set aside following World War I by the Ancient Order of the Sons and Daughters of Moses for the recreation of African American children. Both Georgetown and the West End neighborhood across the Rock Creek were historic predominantly African American communities joined in the early twentieth century by the original P Street Bridge dating from before the Civil War. Concerned that the area’s overcrowded streets and alleyways were no place to play, the society’s elders raised the money to knit together a park for their community’s children. Known variously as Pattersons Park, Jacobs Park, and Winships Lot, these community grounds eventually fell under control of the D.C. Department of Recreation, which undertook major renovations just before the outbreak of World War II.

The park and its community thrived. Nearby Mt. Zion Church and other churches banded together to organize summer camps and Boy Scout troops, while the Rose Park Warriors played other amateur baseball teams across the city. Tennis stars Roumania and Margaret Peters, who lived around the corner at 2710 O Street, learned their skills at the local courts, as did many a standout basketball player.

Washington was a Jim Crow town at the time and the presence of white and black children playing together offended municipal authorities. Beginning in the 1940s, whites began to move into Georgetown in a very early example of the process of private revitalization now known as “gentrification.” AnchorIn desperation, around 1945, the D.C. Recreation Department started posting signs warning that the park was “For Coloreds Only.” This move was widely protested by black and white community members alike, forcing authorities to accept Rose Park as the first integrated recreational area in the District of Columbia.

In 1947, freshman Congressman John F. Kennedy joined the gentrifiers, as did several of his family members and friends. A few years later, he proposed to Jacqueline Bouvier in a booth at Georgetown’s Martin’s Tavern and settled into an impressive Federal-style row house at 3307 N Street, NW to start a family. Both daughter Caroline and son John, Jr. were born in that house before the family moved to the White House in 1961. For young mother Jacqueline and daughter Caroline, Rose Park was their playground. African American Washingtonians of a certain age fondly remember playing with Caroline as Jacqueline looked on.

Jacqueline was already familiar with Black Washington, having studied photography as a young reporter with master African American photographer Robert Scurlock at his famous studio on U Street in the heart of the city’s Black community. At Rose Park, she is remembered as having mixed with her African American neighbors with ease.

Rose Park hardly was a biracial paradise. More often than not, Blacks and Whites were alone together as they enjoyed the playground, rarely crossing over the color boundary in any meaningful way. The area nonetheless was unique among the city’s recreational facilities for embracing all comers regardless of their race. It provided a model of what the city and country could become.

In all probability, very few of those enjoying the park today know this history. African Americans were pushed out by planning and zoning regulations intentionally designed to drive them away. Over time, the park became the playground for the neighborhood’s new residentswho were whiter and wealthier than those who came before. They benefit from the foresight and civic vision of the elders of the Ancient Order of the Sons and Daughters of Moses. Rose Park, in this regard, is an example of how urban space can evolve over time, enriched by its own past and those who created it.

Author

Former Wilson Center Vice President for Programs (2014-2017); Director of the Comparative Urban Studies Program/Urban Sustainability Laboratory (1992-2017); Director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies (1989-2012) and Director of the Program on Global Sustainability and Resilience (2012-2014)

Urban Sustainability Laboratory

Since 1991, the Urban Sustainability Laboratory has advanced solutions to urban challenges—such as poverty, exclusion, insecurity, and environmental degradation—by promoting evidence-based research to support sustainable, equitable and peaceful cities. Read more

Explore More in Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Browse Building Inclusive and Livable Cities

Hometown D.C.: America's Secret Music City

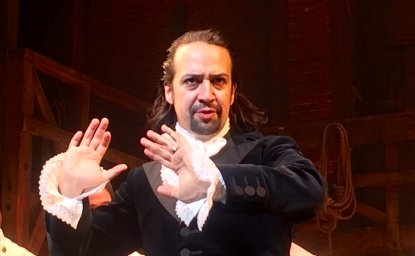

Bringing New York to the Broadway Stage

10 Steps to a More Genuine DC Experience