The Commission on Agricultural Workers (CAW) was created in Section 304 of the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 to answer nine farm labor questions, including how IRCA's Special Agricultural Worker (SAW) legalization program and IRCA's employer sanctions affected US farm workers and farm employers. CAW also dealt with farm labor questions not linked directly to IRCA, such as whether agriculture relies on a temporary workforce and whether farm employers have trouble finding US workers because they do not use modern labor-management techniques.

The CAW’s conclusions and recommendations were dominated by the unexpected effects of IRCA. Instead of reducing unauthorized migration, IRCA contributed to more unauthorized Mexico-US migration and fueled a false documents industry that helped some unauthorized foreigners to legalize their status and others to satisfy I-9 employment verification requirements despite being unauthorized. Individual SAWs benefited because their legal status increased their mobility in the US labor market, enabling many to find nonfarm jobs and achieve higher incomes.

However, the treadmill farm labor market that involves newcomers with few US job options accepting seasonal farm jobs until they find better US jobs did not change after IRCA. Instead of immigration reform ushering in a new farm labor era that transformed seasonal farm work from a job into a career, the early 1990s were marked by falling real wages and more workers brought to farms by labor contractors. As with the 1950 Truman Commission on Migratory Labor, the CAW concluded that there was no need for additional foreign guest workers.

SCIRP to IRCA

IRCA was an outgrowth of the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy (SCIRP), whose major recommendation in 1981 was to couple amnesty for unauthorized foreigners with sanctions on employers who hired unauthorized workers. SCIRP made only one farm-labor recommendation (6E): “that government, employers, and unions should cooperate to end the dependence of any industry on a constant supply of H-2 workers" (SCIRP Staff Report, 1981, pii). Employers asked "where will we get enough US workers to do the jobs that have to be done," (p 668), while farmworker advocates argued that temporary foreign workers should be "a short run supplement…during periods of unusual domestic labor shortages…" (p 667).

In the early 1980s, the H-2A program brought mostly Jamaican guest workers to Florida to hand cut sugar cane and to harvest apples in the northeastern states. Western and especially California growers argued that the H-2 program required a level of planning for labor needs that was not possible due to the many perishable commodities they produced. Western growers wanted a free-agent program that would allow them to hire guest workers without first trying to recruit US workers and would not require employers to house guest workers.

As the House debated IRCA in 1984, the Farm Labor Alliance (FLA), a coalition of 25 western farm organizations, persuaded Rep Tony Coehlo (D-CA) to introduce a free-agent guest worker program as an alternative to the H-2 program. Senator Alan Simpson (R-WY) and Rep Romano Mazzoli (D-KY), the main architects of IRCA, strongly opposed a free-agent guest worker program because IRCA aimed to reassert US government control over immigration, and they feared a loss of control over free-agent guest workers who would not be tied to any employer. However, in what the New York Times called one of the top 10 political stories of 1984, the free-agent Panetta-Morrison guest worker program was approved by the House in June 1984, and in 1985 the Senate agreed to a similar free-agent program offered by Senator Pete Wilson (R-CA) after it was capped at 350,000 admissions a year.

Most of the leading supporters of IRCA strongly opposed free-agent guest workers for agriculture; they believed that changes to the H-2program in the renamed H-2A program were sufficient to assure an adequate supply of farm workers. During the summer of 1986, Rep Charles Schumer (D-NY) negotiated the SAW-RAW compromise between Rep Howard Berman (D-CA), who represented worker interests, and Rep Leon Panetta (D-CA), who represented growers.

The Schumer compromise created the Special Agricultural Worker and Replenishment Agricultural Worker programs: SAW to legalize and stabilize the illegal farm workforce by making workers legal and empowering them to demand higher wages, and RAW to legalize or admit free agent guest workers if SAWs quit doing farm work and there were farm labor shortages. The SAW-RAW compromise was accepted by Congressional leaders, who warned IRCA supporters to accept SAW-RAW without change in order to enact IRCA.

The SAW-RAW compromise was opposed by the INS, but President Reagan nonetheless signed IRCA into law November 6, 1986, after midterm elections that saw Democrats hold their majority in the House and retake control of the Senate. CAW was asked to explore what type of foreign worker program (if any) should be developed for agriculture and to generate the reliable data and analyses that Congress acknowledged were missing from the pre-IRCA debate over agricultural guest workers.

CAW Questions

IRCA asked the CAW to answer nine questions, including the impacts of the SAW program on the wages and working conditions of US farm workers, whether workers legalized as SAWs exited the farm workforce, the impacts of employer sanctions on the farm labor supply, whether US agriculture needs supplementary foreign workers, the extent of unemployment among US farm workers, and whether better labor-management techniques would yield more US farm workers.

IRCA legalization and employer sanctions did not have their expected effects of tightening the supply of farm labor. There were no farm labor shortages in the early 1990s. Instead, even farm employers acknowledged a general oversupply of farm workers, and statistical data reported declining farm wages and worsening working conditions. IRCA boomeranged, adding more unauthorized farm workers rather than reducing their number.

The oversupply of farm labor dominated the CAW’s findings. Real wages fell, labor-intensive agriculture expanded, and the labor contractors who had played a role in providing workers with false documents to apply for legalization under SAW now offered false documents to newly arrived unauthorized workers to satisfy IRCA’s employment verification requirements. The CAW criticized the SAW program for being industry- and worker-specific and for legalizing only workers and not their families.

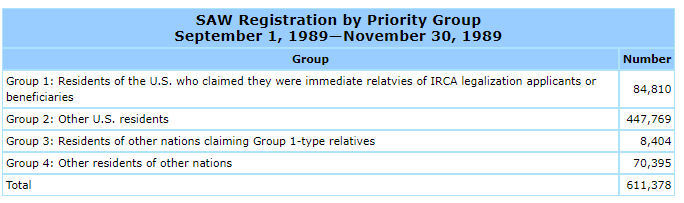

Perhaps the most important CAW conclusion was: “there is currently no need to supplement the farm work force with additional foreign workers beyond those authorized through the existing H-2A program.” This represented a defeat for the western growers who wanted a free-agent guest worker program. Nonetheless, over 600,000 unauthorized foreigners in the US and foreigners abroad registered for the RAW program in three months of 1989, hoping for work authorization documents in the event of farm labor shortages that would have allowed them to do sufficient farm work to earn immigrant visas.

The CAW decried the dis-organization of the farm labor market, and urged more data, reformed institutions, and changed attitudes to better match seasonal workers with jobs. The CAW also recommended more enforcement: “All laws related to farm labor should be uniformly enforced by the agencies concerned so that employers not in compliance do not gain an unfair competitive advantage over those employers in full compliance with the various laws and regulations.” (pxxx).

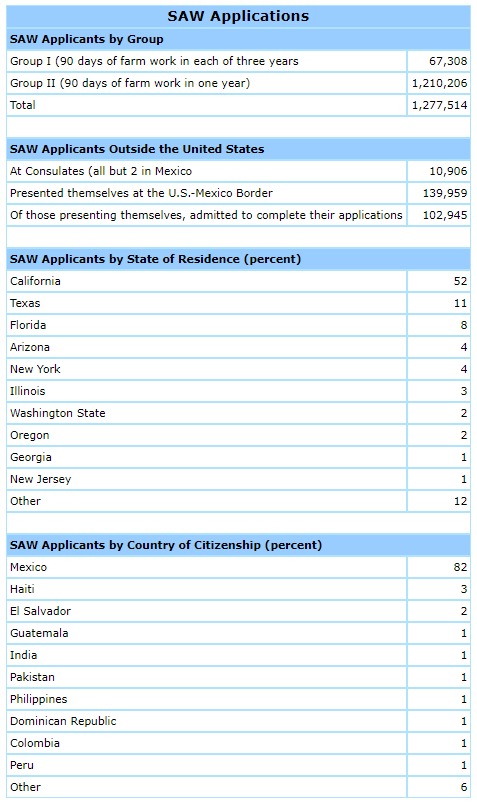

Almost 1.3 million unauthorized foreigners applied for SAW legalization; over 1.1 million were approved. 82% of applicants were Mexican, and 52% applied in California

Over 600,000 unauthorized foreigners registered for the RAW program in 3 months in 1989

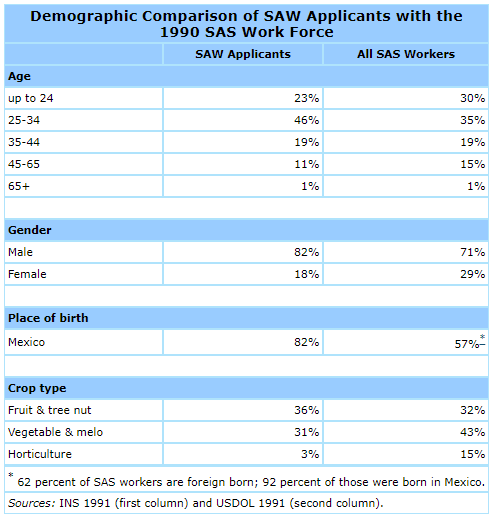

82% of SAW applicants were men, and 82% were from Mexico; two-thirds worked in fruits and vegetables

IRCA’s Effects

IRCA’s agricultural provisions were a case of good intentions gone awry. The SAW-RAW compromise was intended to benefit unauthorized farm workers with legal status, and to ensure sufficient legal workers to harvest US crops. SAWs benefited, largely because legal status increased their mobility in the labor market, allowing them to move throughout the US and making it easier for them to find nonfarm jobs.

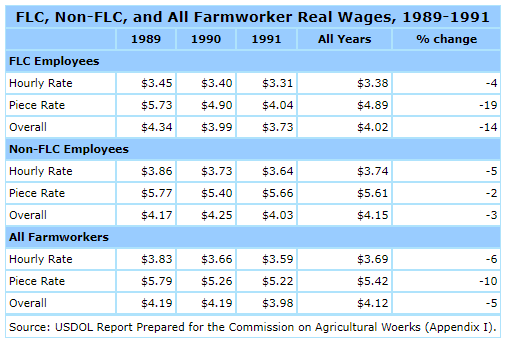

However, wages and working conditions for the two-thirds of farm workers who were not SAWs deteriorated. Real wages dropped for all farm workers, but especially for workers employed by labor contractors.

Real farm wages dropped between 1989 and 1991, especially for FLC employees

The CAW emphasized that too many unauthorized foreigners applied for and were approved for SAW legalization. One estimate was that 400,000 unauthorized foreigners would qualify because they did at least 90 days of work in Seasonal Agricultural Services in between May 1, 1985 and May 1, 1986. However, because the SAW program made it “easy” to obtain an immigrant visa, planners thought that up to 800,000 might apply, so 800,000 applications were printed. However, there were almost 1.3 million SAW applications, and 85 percent were approved.

Farm employers and worker advocates agreed that many farm workers were paid in cash, so that they workers seeking to legalize may not have records of their work as unauthorized workers. The New York Times, in a front-page story that concluded that SAW led to “one of the most extensive immigration frauds ever perpetrated against the US government,” in part because of the allocation of the burden of proof.

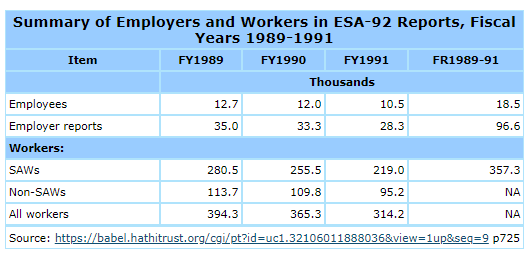

Under the general legalization program, applicants had to prove continuous residence since 1982 to the satisfaction of INS adjudicators. Under SAW, by contrast, once applicants applied, INS adjudicators had to disprove assertions that the applicant picked tomatoes for 92 days in Stockton supported by a one-sentence letter from a labor contractor. Farmers had to report the SAW workers they employed between 1989 and 1991, and they reported 357,300, suggesting the 400,000 estimate was credible. On farms reporting SAWs, they were two-thirds of employees.

357,300 SAWs were reported by farm employers once in the 12 quarters of FY89-91, but less than 20 percent were reported by employers in at least 9 of the 12 quarters

2020

In 2020, three decades after the last major federal government intervention that aimed to transform the farm labor market, there is continuity and change. The share of workers on US crop farms who were born in Mexico has been two-thirds for three decades, far higher than before IRCA was enacted. The share of farm workers who are unauthorized has been half or more throughout US agriculture, double the 25 percent share of unauthorized workers in selected California crops before IRCA was enacted. Nonfarm labor contractors, custom harvesters, and farm management services have become more important in the farm labor market, and now bring more workers to farms than are hired directly by farmers in California.

The farm labor market in 2020 is at another crossroads. The unauthorized farm workers who are the core of the current crop workforce are aging and settled in one place, explaining why follow-the-crop migrants are less than five percent of US farm workers. The children of seasonal farm workers who are educated in the US do not follow their parents into the fields.

Three major factors are creating a race in the fields between machines, migrant H-2A workers, and imports. Real farm wages are rising in major farming states due to rising state minimum wages and the slowdown in unauthorized Mexico-US migration after the 2008-09 recession. The H-2A program is expanding rapidly, especially in states such as California and Washington with high minimum wages and laws and court decisions that require overtime pay for farm workers and paid sick leave. Meanwhile the Covid-19 pandemic has reduced grower prices for many commodities, putting farmers in a cost-price squeeze.

Rising labor costs are encouraging producers of some commodities to further mechanize,, as in raisin and wine grapes. Producers of commodities that are harder to harvest by machine, such as iceberg lettuce and fresh tomatoes, are relying more on H-2A guest workers. Commodities in which marketers play key roles in developing plant varieties and selling fruit such as berries are expanding partnerships with producers abroad, taking advantage of labor costs in rural Mexico that are a tenth of US farm wages.

Producers of all commodities are seeking lower-cost ways to produce and market fresh fruits and vegetables. The exact response, and the speed of change, varies by commodity. Commodities that are undergoing shifts for market reason, such as new apple varieties such as Cosmic Crisp, are planted so that tree limbs form fruiting walls that increase the productivity of hand harvesters and facilitate machine harvesting. Commodities that are shrinking for market reasons, such as raisin grapes, are often replacing hand-harvested vineyards with machine-harvested almonds.

2050

What are the likely parameters of the 2050 farm labor market, when the US is projected to have 400 million people and the world 10 billion? The demand for food and fresh produce is likely to be higher with larger and more affluent populations in the US and abroad.

The US is expected to remain the world’s major exporter of agricultural commodities, and the current pattern of exporting corn, grains, and meat and importing fresh fruits and vegetables is projected to persist. Production of fresh fruits and vegetables in protected culture structures that range from green to shade houses is likely to increase, raising yields, reducing pest and disease pressures, and making farm work more year round and similar to factory work.

The farm workforce may also change. Machines and mechanical aids have reduced the lifting and lugging that made harvesting fruits and vegetables a job dominated by 20- to 40-year old men. Women are now a third of US crop workers, and a higher share of workers are employed in protected culture farming where trolleys and other aids make farm work easier. The future may involve more older workers in their 50s and 60s able to do farm work behind conveyor belts in fields or sorting mechanically harvest produce in packing houses.

A major question is whether the farm labor market in 2050 will offer jobs or careers. The framers of IRCA believed that, by legalizing unauthorized workers and cutting off the supply of unauthorized newcomers, farm employers would have to raise wages and improve working conditions to retain experienced workers. Instead, wages fell, legalized farm workers exited, and unauthorized newcomers replaced them in a labor market with ever-more intermediaries.

Protected culture farm work in 2050 may be like warehouses work today, with the workers hired directly and supplied by intermediaries closely monitored and subject to automation. Work in open fields is likely to feature more machines and mechanical aids. In some commodities, there may be a return to past practices, perhaps harvesting a commodity by machine and then sorting and packing it in packinghouse.

Members of the CAW

- Henry J. Voss, Chairman**

Director

California Department of Food & Agriculture, Sacramento, California - George F. Sorn, Vice Chairman*

Executive Vice-President

Secretary-Treasurer, Florida Fruit and Vegetable Association, Orland, Florida - Honorable Richard B. Abell*

Former Assistant Attorney General

U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. - Dolores Huerta***

First Vice-President

United Farm Workers, AFL-CIO, Keen, California - Lloyd W. Aubry, Jr., Esq.*

Director

California Department of Industrial Relations, San Francisco, California - Cardinal Roger Mahoney***

Archbiship of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California - Michael V. Durando*

President

California Grape and Fruit Tree League, Fresno, California - Clarence E. Martin, III, Esq.**

Principal

Martin & Seibert, L.C., Martinsburg, West Virginia - Ben M. Gramling, II**

President

Gramling Brothers, Gramling, South Carolina - Philip L. Martin, Ph.D.*

Professor

Department of Agricultural Economics, University of California, Davis, California - Russell L. Williams***

President

Agricultural Producers, Valencia, California

Served Partial Term, Not Signatory

- Othal E. Brand*

Mayor of McAllen

Griffin and Brand of McAllen, Inc., McAllen, Texas - Russell Pitzer**

Manager

Tri-County Growers, Inc., Martinsburg, West Virginia

* Appointed by the President

** Appointed by the President Pro Tempore of the Senate

*** Appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives

CAW Case Studies

- The Tomato Industry in California and Baja California

David Runsten, Roberta Cook, Annd Garcia, Don Villarejo - The Citrus Industry in California and Arizon

Herbert O. Mason, Andrew J. Alvarado, Gary L. Riley - The Raisin Industry in California

Andrew J. Alvarado, Herbert O. Mason, Gary L. Riley, John W. Hagen - The Agricultural Industries in Oregon

Robert Mason, Timothy Cross, Carole Nuckton - The Apple and Asparagus Industries in Washington

Edward Kissam, Anna Garcia, David Runsten - The Pickle Cucumber and Apple Industries in Southwest Michigan

Edward Kissam and Anna Garcia - The Applie Industry in New York and Pennsylvania

David S. North and James S. Holt - The Peach Industry in Georgia and South Carolina

Sandra L. Amendola, David Griffith, Lewell Gunter, Jr. - The Winter Vegetable Industry in South Texas

Luis F.B. Plascencia, Robert W. Glover, Brian Craddock - The Winter Vegetable Industry in South Florida

CAW Research Reports

- U.S. Farmworkers in the Post-IRCA Period

Richard Mines, Susan Gabbard, and Ruth Samardick - The Effect of IRCA on Farm Employment and Wages

James A. Duffield and Haryy Vroomen - SAWs Working in Agriculture, 1989-1991

Robert Coltrane - An Assessment of the Process Underlying RAW Calculations

Wallace E. Huffman - IRCA and the Relationship Between Farm and Nonfarm Wages

Commission on Agricultural Workers Staff - IRCA and Hired Farm Labor's Share of Cash Receipts from Marketing

Commission on Agricultural Workers Staff - Employment Trends in the United States and Seven Key Agricultural States

Commission on Agricultural Workers Staff - Employers, Employment, and Wages Paid in California

Commission on Agricultural Workers Staff

References

Commission on Agricultural Workers. 1993. Final Report.

Commission on Agricultural Workers. 1993. Hearings and Workshops.

Commission on Agricultural Workers. 1993. Case Studies and Research Reports.

Suro, Roberto. 1989. Migrants' False Claims: Fraud on a Huge Scale. New York Times.

Author

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Farm Labor & Rural Migration News Blogs

Farm Labor and Mexico's Export Produce Industry

Water Security at the US-Mexico Border | Part 1: Background