Iran, Without Details, Indicts Several Detainees Who Have Dual Citizenship

Iran’s security agencies remain obsessed with people who have dual citizenship, whom they perceive as threats to the Islamic Republic.

Iran’s security agencies remain obsessed with people who have dual citizenship, whom they perceive as threats to the Islamic Republic.

Iran’s security agencies remain obsessed with people who have dual citizenship, whom they perceive as threats to the Islamic Republic.

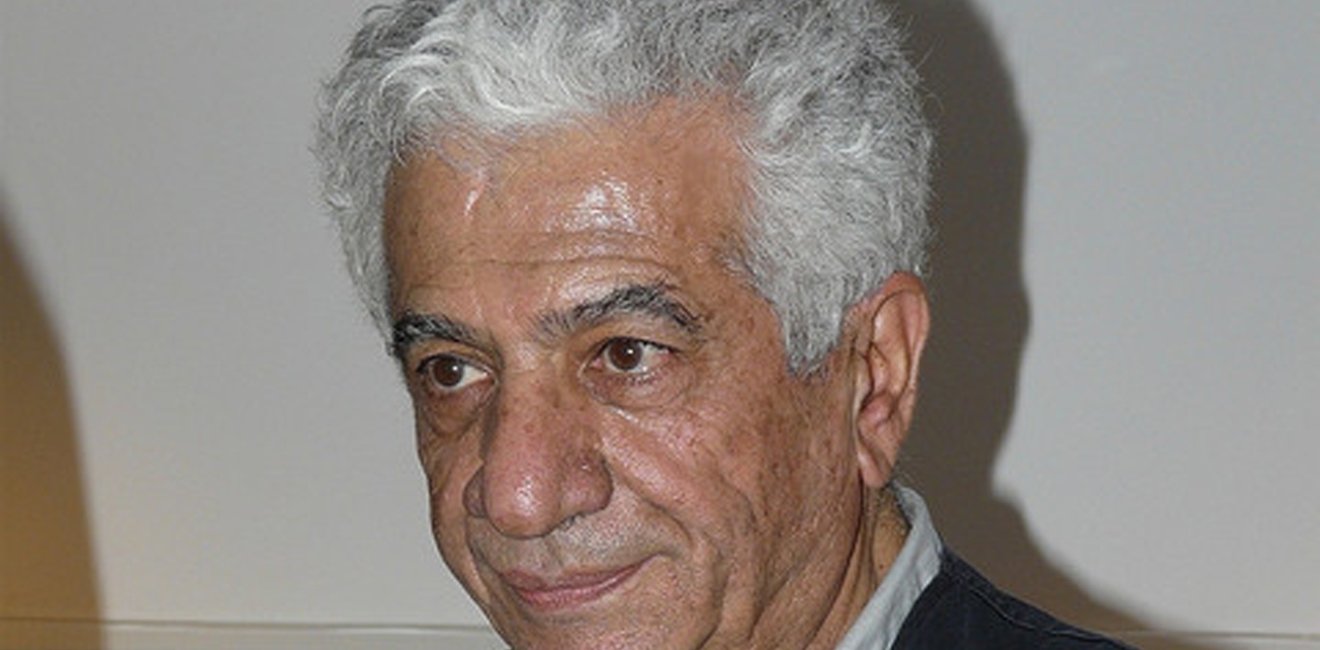

Early this month Iranian authorities confiscated the passport of sculptor and painter Parviz Tanavoli as he was about to fly to London. Art lovers worldwide and Mr. Tanavoli were puzzled as to why, with no explanation, the 79-year-old was prohibited from flying to London for a book launch and to deliver a lecture at the British Museum. This weekend Iran’s “reasoning” emerged: Mr. Tanavoli said after a court appearance Sunday that he has been accused of “causing confusion in the public mind” and “spreading lies,” allegedly through his sculptures.

One of Mr. Tanavoli’s pieces stands prominently in the entrance hall of the British Museum. His works have been acquired by the Tate Modern in London and the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. In 2008, one of his pieces sold for $2.8 million at a Christie’s auction. It would be difficult to read political meaning into his art, which include trademark iterations in bronze and other materials of the Iranian word for “nothing” (hich). A citizen of both Iran and Canada, he has been dividing his time between the two countries and runs a workshop for art students in Iran.

Mr. Tanavoli is one of several Iranians with dual citizenship who have attracted the attention of the country’s security agencies. Iran does not recognize dual citizenship. Iranian-American Siamak Namazi was prevented from leaving Iran last July. After being interrogated for months he was arrested in October and remains in jail. His 80-year-old father, Baquer, was later told he could visit his son and traveled to Iran, where he wasarrested in February. Many observers think that Baquer, who has a heart problem, wasdetained to coerce his son into making a false confession.

Nazak Afshar, a French-Iranian dual citizen and a former employee at the French embassy in Tehran, was arrested after arriving at the Tehran airport in March in an attempt to visit her sick mother.

Ayatollah Khamenei is skeptical of the social openness that President Hassan Rouhani has sought to pursue, fearing that such policies would destabilize the regime.

In April Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, an Iranian-British citizen who works for the Thompson Reuters Foundation in London was stopped at the airport and arrested. She was later transferred to a jail in Kerman, in eastern Iran. Ms. Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s 22-month-old daughter, who has only British citizenship, was taken from her and given to her parents, who live in Tehran.

Homa Hoodfar, a retired Canadian-Iranian professor of anthropology, was in Iran doing research on women’s issues when she was initially arrested in March. She was released on bail, but Iranian authorities kept her travel documents and computer. She was arrested again last month and is being held in Evin Prison in Tehran.

Tehran’s prosecutor announced Monday that Ms. Hoodfar, Siamak Namazi, and Ms. Zaghari-Ratcliffe have been indicted. Details have not been released. Several others with dual citizenship linger in Iranian prisons.

Often Iran’s security authorities offer no explanation for these arrests for months. When charges are announced, they are almost invariably the same, whether the “offender” is a businessman, university professor, artist, policy analyst, or employee of a nongovernmental organization working on poverty alleviation. These people are accused of collaborating with enemies of Iran, plotting with foreign governments to undermine and overthrow the Islamic Republic. Credible evidence has not been publicly produced to support such charges.

These arrests and the imprisonment of intellectuals, journalists, feminists, and activists in Iran reflect a paranoia that has intensified in the 36 years since the revolution. The result has been to create a pervasive sense of mistrust and insecurity, an aura that Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei feeds.

To thwart widespread expectations that more open relations with the West would follow the signing of the international agreement on Iran’s nuclear program last year, Ayatollah Khamenei has repeatedly warned of thedangers of political and cultural “infiltration” of Iran by the U.S. and its European allies. Iran’s security agencies, including the fearsome intelligence arm of the Revolutionary Guards, take such warnings as a green light for their activities. The persecution of dual nationals has been a predictable result.

Ayatollah Khamenei is skeptical of the social openness that President Hassan Rouhani has sought to pursue, fearing that such policies would destabilize the regime. His nightmare is a recurrence of the massive protests that followed the 2009 presidential election in which the unpopular incumbent was declared the winner. Many Iranians believe the election was rigged; the supreme leader has talked about it as a blessing.

To ward off what he perceives as threats to the regime, the supreme leader increasingly relies on the Revolutionary Guards and its police arm, on the basij paramilitary forces, on the intelligence agencies, and on the judiciary, with its compliant array of Revolutionary Courts, which often operate behind closed doors. Meanwhile, President Rouhani focuses on improving Iran’s economy and employment situation. He appears to have given up on efforts to end the most blatant violations of human rights.

Photo Source: Flickr User Masih Azarakhsh (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the author.

This article originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal

The Wilson Center’s Middle East Program serves as a crucial resource for the policymaking community and beyond, providing analyses and research that helps inform US foreign policymaking, stimulates public debate, and expands knowledge about issues in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Read more