One must credit the global COVID-19 pandemic with elevating supply chains and logistics to a position of prominence in international business. The wake-up call began with shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), particularly N95 face masks and ventilators. Interruptions in the supply of basic materials due to factory and port shutdowns in China, congested port operations in Valencia, Singapore and Bremerhaven, shortages of workers such as truckers, and warehouse space limitations continue to hamper global trade. Supply chain disruptions have caused widespread and deep negative impacts on production, distribution, and pricing, which has affected both producers and consumers alike.

Besides the operational issues surrounding supply chains, there is the challenge of supply chain sustainability. Recognizably, the sustainability of supply chain management means integrating environmentally and financially viable practices into the complete supply chain lifecycle.[1] Presently, sustainability is usually understood as “green” supply chain management; and supply chains, recognizably, have a far greater impact on the environment than any other part of their operations.

Operations management scholar S.K. Srivastava defines the scope of Global Supply Chain Managed Solutions (GSCMs) as ranging "from reactive monitoring of general environmental management programs to more proactive practices implemented through various Rs (Reduce, Re-use, Rework, Refurbish, Reclaim, Recycle, Remanufacture, Reverse logistics, etc.).”[2]

Green supply chain practices aim to help industries reduce their carbon emissions and minimize waste while maximizing profit. Utilizing paper instead of plastic (a petroleum-based product) is a prime example. Not only is rethinking input materials one way of utilizing and implementing green supply chains practices, but so are reusing waste or by-products, curtailing packaging, redesigning processes, and optimizing transport.[3]

Additionally, there are links between improved environmental performance and financial gains. General Motors (GM), for example, reduced disposal costs by USD $12 million by establishing a reusable container program with its suppliers. Perhaps, General Motors may have been less interested in green issues if they were making record profits, but in an attempt to reduce costs in their supply chain, GM found that the cost reductions they identified complemented the company’s commitment to the environment.[4]

Factors affecting GSCM practices encompass leadership commitment, technology, brand image and company culture, cost and knowledge.[5]

In North America, home to the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the continuing drift away from globalization and towards regionalization combined with the growing attention to sustainability by governments, companies, and environmental interest groups, have combined to shine the spotlight on supply chains.

The status, policies and outlook for green supply chains in North America are the focus of this monograph—one which we hope will shed light on the progress to date and remaining challenges facing the public and sectors in the US, Mexico, and Canada.

Green Supply Chains in the United States

To begin with, what is the status of the adoption of GSCM in the United States, in general?

In the United States, due to more environmental awareness among the general population, the public sentiment and pressure from activists is forcing many organizations to adapt green practices in various parts of their value chain.[6] Organizations have realized the environmental impact of their practices and have become more conscious of their corporate and social responsibilities.[7] In spite of these motivators, adoption of sustainable practices particularly in supply chains has been challenging. For instance, according to the 2021 State of Supply Chain Sustainability report by the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics and Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP), the collected sustainable supply chain-related data from over 2,400 respondents suggest that only 59 percent of the companies had invested in green supply chain practices in 2020.

This is despite major industry players taking significant steps towards sustainable supply chain management practices. Gartner released their annual report titled, “Global Supply Chain Top 25” where companies were scored on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) initiatives.[8] Environmental, Social and Governance corporate performance was introduced in 2006 in the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Investments report. For the first time, ESG criteria was incorporated in companies’ financial evaluations. Since then, ESG performance assessment has become a thriving sector that continues to grow. This report identified 19 companies (out of the top 25) that achieved the highest possible ESG scores and among them were industry leaders such as Cisco Systems, Schneider Electric, PepsiCo, Intel, and more. For instance, Cisco (which has retained the number 1 spot in this report for 3 years in a row) implements a Supplier Code of Conduct that requires suppliers to maintain a socially responsible supply chain. Their suppliers are expected to publicly disclose greenhouse gas emissions and report information on the environmental impact of their operations. Additionally, Cisco collaborates with the Responsible Minerals Initiative, an alliance of more than 400 companies, to ensure the ethical sourcing of minerals while upholding human rights and environmental sustainability.[9]

Similarly, PepsiCo also follows a Supplier Code of Conduct and a Sustainable Sourcing Program (SSP) which focuses on suppliers and is composed of formal risk assessments, third-party audits, corrective action, and capability building to ensure meeting sustainability standards of the company. Another one, among many such programs, called Sustainable Farming Program (SFP) focuses on assessing the company’s direct farmers and growers, protecting human rights, and implementing regenerative agricultural practices.[10]

These are just a few examples of United States-based corporations that are attempting to adapt green supply chain practices. Companies have begun focusing on making human, social, and environmental factors green or sustainable. This is evident from the focus on human rights and worker treatment protection initiatives for individuals involved in various parts of the supply chain and the carbon footprint and greenhouse gas emission policies that industry leaders are implementing.

To continue, what are the primary forces and factors that are driving green supply chain adoption and implementation?

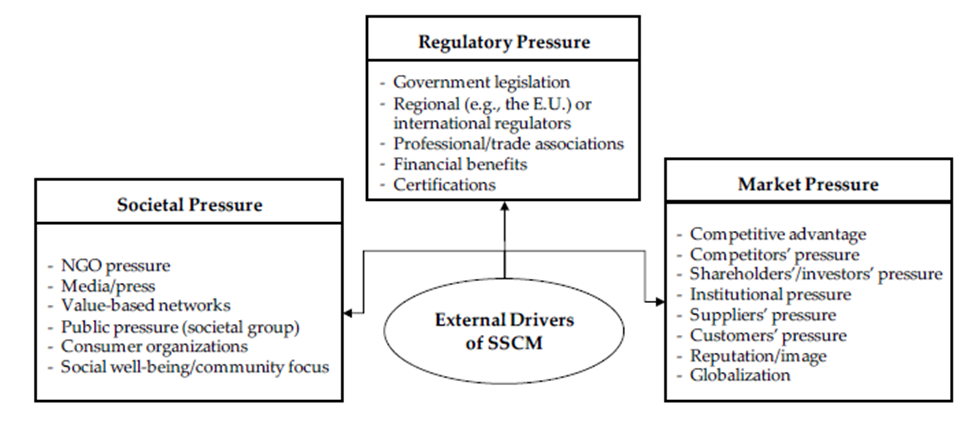

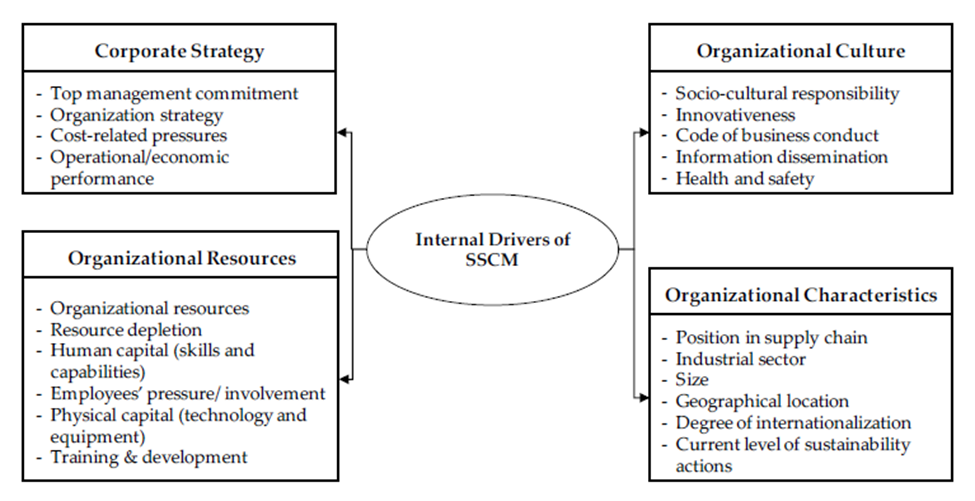

The adoption of green supply chains has had driving forces behind it since the late 2000s. In a review of drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management (SSCM), Saeed and Kersten (2019) classified external and internal factors responsible, which can broadly be summarized into the following: (1) external drivers—market pressures, societal pressures, regulatory pressures; and (2) internal drivers--corporate strategy, organizational culture, organizational resources, organizational characteristics.[11]

Figures 1 and 2 elaborate on these external and internal drivers.

Figure 1: External Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management[12]

While these drivers are global, arguably, most of these factors are affecting the adoption of SSCM in the United States. In the case of Oracle, where pressure from consumers and investors’ financial preference for sustainable retailers led the computer software giant to introduce Oracle Retail Supplier Evaluation Cloud Service, thereby adding ethical and environmentally friendly supply chain practices with more visibility and transparency. The evaluation application allows suppliers to evaluate their practices for ethical, environmental, safety, and quality performance. Using the application, retailers can now implement better risk management, protect brand image and find ethical sourcing options, making their overall supply chain much greener.[13]

Further to this point, we can discuss examples of SSCM adoption due to one of more internal factors that are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Internal Drivers of SSCM[14]

As seen in Figure 2, employees’ pressure/involvement is an important internal factor driving SSCM. This is apparent in the US context where, in a 2021 survey of organization preferences, almost 44 percent of millennials and 43 percent of Gen-Zers identified climate change and the environment as a top concern, adding a preference for finding employment at companies that address sustainability issues in all aspects of organizations, including supply chains[15]. This clearly shows the importance of organizational climate and resources in driving green supply chain practices among other internal factors.

What are the primary forces and factors impeding green supply chain adoption and implementation?

In a recent literature review by Leffering & Trienekens for Business Management and Organization Group (BMO), the authors identified three key barriers to Green Supply Chain Management adoption, mainly, 1) implementation cost of sustainability in the supply chain, 2) supply-side obstacles, and 3) lack of governmental subsidies.[16]

Moreover, the 2021 State of Supply Chain Sustainability research by MIT’s Center for Transportation & Logistics (MIT CTL) and the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) gives insight into the barriers that 20 enterprises face to the successful adoption of supply chain in the United States. Most of the interviewees pointed out that developing partnerships and bringing suppliers on the same page about sustainability is the key challenge. This is because the expectations and enthusiasm related to GSCM between the supplier and manufacturer may vary widely. Often, these suppliers are small enterprises with a different set of priorities and concerns than the environment.

Next, industry leaders typically deal with large and complex supply chains, which complicates reviewing whether the standards set by policy and supplier codes of conduct for sustainability are followed to satisfaction or not. Additionally, any transgressions on the suppliers’ side do end up harming the corporate customers as well, creating further challenges to identify, and manage risks to the company.

For instance, Toyota has managed to create a sustainable global chain accounting for human rights, labor environments, and the natural environment in all regions from where they source materials.[17] However, the company still announced a cut of more than 50,000 vehicles from production due to supply shortages of semi-conductors.[18] While this shortage is primarily due to COVID-19 shutdowns, it reflects a dependency of corporations on their global suppliers, highlighting the importance of harmony goals between suppliers and their corporate clients and the complex clockwork needed for a successful GSCM.

Additionally, government policies and regulations in the US have proven to be both a driver and a barrier to GSCM practices, which prompts the critical question: What role does the federal government play in supporting GSCM (policies, regulations) and how is it faring.

While many state legislatures have regulations and policies in place affecting GSMC adoption, we will focus on the steps taken by the US government to discuss overall regulations in the country. The US General Services Administration (GSA) has recognized the need to reduce energy and environmental footprints and hence collaborates with industry partners to create best practices for supply chain management in the services provided to the federal government. This is a case of leading by example, whereby all government contractors are expected to abide by green supply chain management practices.

For instance, GSA has been a member of CDP Supply Chain, a third-party supply chain disclosure system, since 2015. But surprisingly, government contractors are not required to report energy and environmental performance data through CDP, and only a small proportion of these contracts report their sustainability impact performance. In 2019, the government-wide supply chain emissions from federal contractors were expected to be around 150 million tons, whereas emissions from federal buildings and non-tactical fleets were expected to be 37 million tons.[19] While intentions to reduce emissions exist, there still is a lot of work to be done to have any significant supply chain emissions impact.

On the other hand, in 2021, the Biden Administration signed Executive Order 14017 on America's Supply Chains, ambitiously titled, “Plan to Revitalize American Manufacturing and Secure Critical Supply Chains in 2022.” Broadly, the plan intended to make American supply chains more sustainable and resilient, with a greater environmental impact. The 2022 report based on four 100-day supply chain reviews shows that while there are significant accomplishments in certain areas, much more needs to be done, particularly in the GSCM for mining and energy sectors.

The plan encourages investments in sustainable domestic production and processing of rare minerals and carbon fiber while ensuring that the US can rely on multiple sources. The administration has updated mining regulations and reformed mining laws to account for sustainable and responsible practices. The core responsibilities have been assigned to the Department of Energy (DOE), which is tasked to create an integrated “mine waste”, critical element extraction, separation, and refinery plants. Additionally, in February of 2022, the Mining Innovations for Negative Emissions Resources (MINER) Program of DOE made available $44 million in funding for “commercial-ready technologies that give the United States a net-zero or net negative emissions pathway toward increased domestic supplies of copper, nickel, lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements, and other critical elements required for a clean energy transition.”[20] The impact that this plan would have on GSCM in the US remains to be evaluated.

It is not only the executive branch of the government that is concerned with GSCM adoption but also the Congress, as it has taken steps to make US supply chains more sustainable. In June 2021, Representative Tim Ryan (D-Ohio) introduced the Critical Supply Chains Commission Act, in the wake of recent supply chain shortages and failures during the Covid-19 pandemic. The bill proposes setting up a National Commission on Critical Supply Chains that can address the current gaps in US supply chains, exposed during the pandemic and consequences, to help make them more sustainable, robust, and resilient. While the bill did not advance beyond the assigned sub-committee, it shows the interest of legislature to intervene in American Supply Chains and their long-term sustainability.

Lastly, to increase corporate accountability, the Securities and Exchange Commission is implementing significant regulations, mandating comprehensive Environment, Social, Governance (ESG) and climate impact disclosures in annual reports by US public companies. This will be another motivation for GSCM adaptation through increased regulation and oversight.

Finally, within the context of international trade and commerce, how do GSCM practices in the United States relate to the US-Mexico-Canada trade agreement?

The USMCA has very direct clauses that relate to GSCM practices in the United States. As stated before, GSCM encompasses more than just environmental and human rights perspectives. According to the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR), USMCA contains a dedicated chapter on the environmental impact of the trade agreement and these provisions are enforceable. It assures that the United States remains committed to all the key multilateral environmental agreements (for example, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna, Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Substances, etc.). Such clauses also address maritime environmental issues including “illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing and harmful fisheries subsidies.” The chapter binds all three countries to establish anti-trafficking policies for timber, fish, and wildlife protection. According to USTR, this is the first time that environmental issues such as air quality and marine litter are accounted for in a US trade agreement.[21]

From the human rights perspective of GSCM, the USMCA’s Rapid Response Labor Mechanism offers a more efficient approach to labor dispute settlements in free trade agreements since it allows an international panel to determine any violations of Mexican Labor Law. Thus, the US and Canada can, based on a good faith belief, request remediation for any specific “Denial of Rights” of workers, thus, providing expedited enforcement of workers’ free association and collective negotiation rights.[22] Interestingly, the agreement also allocates USD $600 million for environmental clauses and effective enforcement of regulations and eliminates a requirement to prove a violation from a trade perspective; the pros and cons of which are debatable.

Overall, what is the outlook for GSCM in the United States and North America in general? Based on our analysis, it is clear that significant progress has been made in GSCM adoption in the US and in North America, but it has not been without its problems and many more advancements need to be addressed. We identify three focal points that can promise a brighter future for the adoption of GSCM: (1) apply more pressure on corporations from different domestic sources; (2) address a lack of transparency; and, (3) increase focus on small businesses.

In conclusion, the state of GSCM in the US is midway from success at best. From private corporations’ perspective, as we can see from the examples discussed earlier, the industry leaders have made sustainability a priority and are revamping their supply chains to make them greener. But the gap lies in the alignment of goals between smaller suppliers, who occasionally cannot afford changes in traditional supply chains to make them more eco-friendly, or small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) who have to maintain capital for day-to-day operations and need profits to fund growth and thus cannot afford to prioritize sustainability.

On the administrative front, the USG has become more aware of the need for sustainable supply chains. By making government policies more environmentally conscious and adopting regulations that encourage private businesses to adopt GSCM practices, the USG has shown promise towards accomplishing its sustainability agenda. However, we are yet to see a collaboration between the government, NGOs, and large and small private enterprises such that all parties operate harmoniously with the same goal of sustainable supply chains. An alliance of this nature is essential to achieving further progress on GSCM.

Green Supply Chains in Mexico

Looking south of the border to Mexico, what is the status of the adoption of Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM)?

In Mexico, there have been efforts to advance green practices since 2008, when the Ministry of Natural Resources of the Government of Mexico (SEMARNAT) led an ambitious green supply chain program in which around 600 SMEs participated. Further, the National Development Plan (2013-2018) included the Climate Change Special Program (PECC 2014-2018) intended to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to improve the government’s ability to respond to environmental climate change.

Furthermore, SEMARNAT published the Official Mexican Standard NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021 in the Official Gazette of the Federation (DOF), which establishes pollutant limits in wastewater discharges. This was an effort to update the 1996 NOM by renewing technical aspects that over time no longer were pertinent.[23]

Grupo Bimbo, a Mexican multinational and the world's largest baking company, is an example of an environmentally responsible company. Bimbo is known for its use of renewable energy and integration of sustainable practices in its logistics for distribution and assembly of electric vehicles. FEMSA, a Mexican multinational beverage and retail company, implements sustainable and strategic logistics with the “last mile” model across its businesses, including the largest convenience store chain in Mexico.[24]

Also, the Mexican Hydrogen Society (SMH) and the Mexican Hydrogen Association (AMH), are taking action to promote the hydrogen industry in Mexico. Their objectives are to develop and innovate hydrogen technologies and hydrogen-related issues. The key strategies provide specialized knowledge and infrastructure to different sectors and create synergies for environmental care through sustainable energy systems. Their efforts also include key activities to establish collaboration to resolve hydrogen concerns from local and worldwide organizations, and to analyze challenges and opportunities. In 2022, the SMH and AMH brought together the international community in an event titled the "H2 Expo Hydrogen" to accelerate the decarbonization of the world economy and emphasize how hydrogen energy will be used in Mexico.[25]

Even though there have been efforts to advance green practices, it is clear that advancements are still dependent on other factors.

In that regard, just what are the primary forces and factors that are driving the adoption and implementation of Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) in Mexico?

Concerns about the impact of human activity on the environment extend back decades. In 2002 the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) supported energy conservation and efficiency through improved policies, promoted green policies for industry, and encouraged authorities to consider sustainability in their development plans.

Various forces and factors drive GSCM in Mexico, such as the common practice of having senior management commit to green operations. Stakeholder pressure plays a key role in implementing green practices along with business performance improvement. In addition, pressure from the government, compliance with Mexican norms, international legal environmental requirements, international treaties and agreements, auditing programs, and certifications have encouraged firms to incorporate environmental principles in their supply chain management.

Other factors such as increased environmental costs, incentives, and the customer demand that companies comply with green requirements are driving factors for the adoption and implementation of GSCM. These practices have also become criteria used to measure and evaluate the success of businesses. Even now, green technologies are considered a cost-effective technique to reduce negative environmental impact without compromising economic competitiveness. Also, sustainable development, as a way of operating the supply chain, provides the means to green practices implementation.

Furthermore, supply chains in different industry sectors in Mexico are looking for green practices as a way to innovate their operations and as a core part of their performance. As a result, GSCM has become a source of competitive advantage.

One must ask, what are the primary forces and factors that are impeding the adoption and implementation of Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) in Mexico?

In Mexico, national and international regulations have encouraged the adoption and implementation of green practices throughout supply chain operations, but they have also become a drawback. This is mainly due to stringent requirements which, in many instances, take a long time to implement, require investment and may result in an unacceptable, or even non-viable, return on investment.

To overcome barriers, government and industry will need to increase their investments in technology development to replace fossil fuels at a faster pace than currently and to migrate all automotive production towards hybrid and electric cars.

Empirical research produced by Jum’a, et al. (2022) reveals that suppliers, customers, cost, and environmental factors significantly influence the adoption of GSCM by manufacturers.[26] This is not far from what Mexico is dealing with today. For example, suppliers can act as a barrier when they fail to fully commit, by deed as well as word, to change towards green practices. Also, a lack of knowledge and understanding can influence their decision-making and reluctance to engage in GSCM. Stakeholders across supply chains are a crucial factor in successfully operating under green principles. However, customers usually demand low-cost products irrespective of the environmental impact. In reality, uncertainty in the market and global competition make it hard for Mexico’s companies to keep costs low while simultaneously implementing GSCM practices.

Maturity in Mexico’s supply chains is critical when discussing green operations. Lack of government support systems, infrastructure, knowledge, and expertise on the topic are barriers to stimulating Mexico’s capabilities to increase and facilitate green practices implementation.

Within the public domain, the question arises: What role is the government playing (federal, state, municipal) in supporting GSCM (policies and regulations) and how is it faring?

The role of the government in Mexico’s GSCM success is crucial. Regulations, policies, taxes, and incentives established by the federal and/or state level governments influence costs, delivery times and reliability, and the efforts to adopt and maintain green practices across supply chain operations.

Government regulations for environmental certification range from recognition systems for companies that meet a series of basic standards that promote the reduction of negative environmental impact to instruments such as management or self-regulation systems. Examples of such systems include ISO 14001, the National Environmental Audit Program (PNAA), the Greenhouse Gas Emissions Program (GEI) and the Environmental Leadership Program for Competitiveness (PLAC), among others.

The PNAA, for example, focuses on companies whose operations and business characteristics may harm the environment and has established an environmental audit rubric to verify that companies comply with federal and local environmental laws and regulations. An environmental audit examines water, waste, energy, environmental emergencies, soil and subsoil, air and noise, natural resources, forests, wildlife, and risk and environmental management.[27]

Additionally, the Mexican Norms (NMX) are another type of regulations issued by the Ministry of Economy, and their application is voluntary in most cases. NMX are classified by sectors, one of them is the Environmental Protection Sector which includes the following categories: water, earth atmosphere, environmental quality and development, water purification, flora and fauna protection, waste, noise, and soil.[28]

These regulations are established by Mexico’s government to support companies' own approach to environmental performance improvement and to deliver general guidelines for achieving sustainable development. The norms also provide the requirements to comply with legal and other policies on environmental care and continuous improvement in the field.

Although these regulations, norms, and standards control the environmental behavior of organizations, there is a lack of emphasis on supply chain operations. The integration of functions and common objectives are essential for supply chain success. As a result, the need to align green actions and sync strategies is vital. Therefore, it is important to develop a national agenda to enhance and encourage government policies and regulations that offer the platform and incentives for GSCM across businesses and their network of operations.

Mexico’s commitment to GSCM, whether in word of deed, must be cast within the context of the USMCA. Therefore, one must ask: How do GSCM practices in Mexico relate to the US-Mexico-Canada trade agreement?

The USMCA entails the reform and upgrading of its predecessor NAFTA. The USMCA and the Environmental Cooperation Agreement (ECA) entered into force on July 1, 2020. The chapter on the environment reflects a robust environmental perspective based on obligations to address green issues and strengthen law enforcement. Environmental development and provisions are a core element of the USMCA agreement. Some of the areas for cooperation include environmental governance, pollution reduction, reducing emissions, natural resource usage, biodiversity and habitat conservation, green growth, and sustainable development.

The USMCA prompted the analysis and redesign of GSCM practices in Mexico and pays special attention to strategic sectors such as the automotive, electronics, steel, and aluminum industries. The agreement’s provisions encourage cross-border commerce by requiring a larger percentage of materials and components from North America, which also requires Mexico to adapt its capabilities and invest in value-added activities from a GSCM perspective.

Green practices such as the increase of renewable energy usage, efficient use of resources, use of green energy and clean technologies, recycling, optimization of transportation systems, and investment in green infrastructure are challenging throughout the supply chain operations in Mexico. Still, the country needs to put in place efforts to protect and conserve the environment as a means of fulfilling its obligations under the USMCA. In February, 2022, The Mexican Hydrogen Association (AMH) and the Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association (CHFCA) signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to promote cooperation between Mexico and Canada in the development and deployment of zero-emission hydrogen and fuel cell technologies. The memorandum outlines different areas of collaboration, including the development of standards, joint government policy initiatives, market intelligence sharing, and the development of a hydrogen strategy for Mexico.[29]

A recent report by McKinsey on Mexico’s energy transition highlights a 65 percent hydrogen production cost decrease compared to other countries, emphasizing that the country could become a global energy powerhouse in clean and renewable energy.[30]

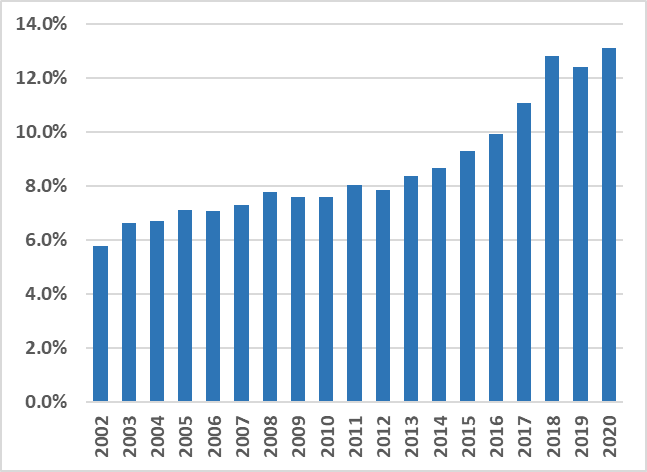

Mexico’s production of renewable and alternative sources as a share of total national energy production has increased over time. The annual sum of hydro, geo, nuclear, wind, biogas, solar, cane bagasse, and firewood energy, divided by the total national energy production in the same year, is expressed in percentage terms. This yearly follow-up of the national production statistics helps create public policies aimed at the sustainable development of the sector. Table 2 displays the yearly results in the last two decades:

Table 2: Percentage of Mexico’s renewable and alternative sources participation in the national energy production.[31]

Table by author.

As a result, GSCM practices in Mexico can offer a competitive advantage in the US-Mexico-Canada trade agreement and competitiveness in the global market.

Finally, one needs to ask: What is the outlook for GSCM in Mexico and North America in general?

Green supply chain management in Mexico poses the challenge of integrating environmental awareness into supply chain operations in an emerging country. The Mexican government and industry leaders are obliged to make decisions on green development and to make sure they comply with national and international demands for low costs and environmentally sustainable performance. Nevertheless, Mexico has the potential to transition to a green economy with reduced environmental impact throughout its supply chain operations, including the products and services it offers.

North America’s adoption of green policies and regulations may require responding to the challenge of integrating and aligning priorities in the environmental agenda. Even though the three countries express their interest in a green approach, in some instances the economic agenda might drive the supply chain operations at the expense of the environment. Though not an easy task, collaboration among the nations is essential to decrease the adverse effects of global supply chain deficiencies.

In sum, GSCM presents challenges on how national or international companies will integrate green practices in their environmental agenda across their supply chain network operations and strategies. And this is especially true about Mexico. Organizational maturity will be a fundamental supply chain requisite for companies to continuously innovate and achieve successful green performance results.

Green Supply Chain Management in Canada

Before the environmental awareness of the 1980s, the responsibility for the environmental management of supplies and operations fell mainly to local business unit managers. As the 1990s progressed, the integration of environmental considerations across supply, production, and distribution chains emerged as a much more effective strategy.

Awareness of the benefits of a holistic approach to supply chain management led to the concept of Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) which academia and supply chain practitioners began to document around 2002-2004.

In their literature review on Green Supply Chain Management, published in 2007 in the International Journal of Management Review, Samir K. Srivastava defines GSCM as the “integrating environmental thinking into supply-chain management, including product design, material sourcing and selection, manufacturing processes, delivery of the final product to the consumers as well as end-of-life management of the product after its useful life.”[32]

To answer the question: What are the primary forces and factors that are driving the adoption and implementation of GSCM from the Canadian perspective? Compliance with legal environmental requirements and auditing programs comes as the first driver of adoption and implementation.

In the legislations where they apply, environmental regulations cover mainly hazardous materials threatening human health, various emission levels applying to noise, air, soil and water pollution, and waste management. We also find restrictions on the use of nonhomologous materials and products and on residual materials. Land use planning, environmental impact studies and public consultations, environmental permits, auditing programs and fines also come to play completing the regulatory frameworks.

Complying with environmental legal requirements and auditing programs demonstrates that a company is allocating resources to meet environmental regulations for their internal operations. Some companies will cascade down these requirements to their direct suppliers (tier 1) and, in some cases, to the indirect suppliers (tier 1+n) no matter where they operate. This will be done through the adoption of a Supplier Code of Conduct, supplier prequalification and qualification assessments, and the establishment of due diligence frameworks.

These suppliers must therefore adapt to double standards, those of the legislation where they operate and those of certain customers who may be more restrictive on certain aspects. Some organizations decide to go beyond compliance and adopt more ambitious commitments. What drives these decisions?

North American companies feel the pressure to demonstrate to consumers, customers, investors, lenders, regulators, and other stakeholders the sustainability of their processes and products. In a context where the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) performance of companies is subject to increasingly rigorous evaluation, more transparency and visibility are expected in the supply chains. The growing expectations for a circular economy and drastically reduced GHG emissions are adding enormous expectations on organizations producing goods and services.

The common thread that underlies stakeholder pressures is a fundamental demand and a need for accurate and robust information. How were the raw materials produced/extracted, marketed, mixed, transported, manufactured, and distributed? Considering the limited life cycle of goods, how will these products and the input materials be reused and recycled?

For many new companies, following the path of sustainability is more of a reflex. This is particularly noticeable among SMEs that are created by young founders (and sometimes not so young) to solve environmental and social problems. The path is more difficult for companies that have been established for a longer time. For them, adopting new practices not only requires considerable financial investment to redesign products, modify processes, and replace certain equipment and machines, but also requires changes in mentality and values.

There is a remarkable distinction between the two business groups. The first group acts in the present offering sustainable products and services while the second group works in the medium term by making sustainable commitments. The most popular commitments at present are those relating to the reduction of GHG emissions, counter deforestation and, more generally, reducing the environmental footprint with particular attention to the use of plastic.

However, there is a loophole in these commitments into which many companies fall: not delivering commitments in due time. Some companies find themselves in a position where their performance does not meet the expectations they have created. A recent article from The Guardian demonstrates this by pointing the finger at five of the world’s biggest agribusiness firms trying to weaken a draft EU law banning food imports linked to deforestation, eight days after pledging to accelerate their forest protection efforts at Cop26.[33]

As for the primary forces and factors that are impeding its adoption and implementation, no doubt that the pressures and expectations listed in the previous section are considerations for developing sustainable and law-compliant products and services. However, it is not crystal clear to decision-makers how these forces materialize and impact an organization’s growth, profitability, and value. Are customers and consumers willing to switch or pay more for green products and services?

Most organizations are compliant first and then opportunistic. In an article published in the Harvard Business Review in 2019, Alexis Bateman and Leonardo Bonanni apply the innovation diffusion theory, a concept originally posed by Everett Rogers, to understand how organizations move toward supply chain transparency.[34] Bateman and Bonanni measure supply chain transparency through supply chain scope (internal operations, direct suppliers, indirect suppliers, and raw materials) and transparency milestones (code of conduct, standards and certifications, performance-based metrics, traceability, and full disclosure).[35]

This classification demonstrates its effectiveness when we take note of the commitments that North American companies currently make in terms of reducing GHG emissions and increasing energy efficiency. Almost all of them tackle their internal emissions and their operations first, and few of them are interested in what is happening with their suppliers and supply chains.

Adopting more environmentally friendly practices can result in lower operating and financing costs. The case of energy efficiency is a good example, but there are other opportunities made possible by new technologies and artificial intelligence (e.g., waste & water recycling, carbon footprint modeling, and reverse logistics responsibility).

As such, there is a strong incentive to change ways of doing things. However, like any other investment project, it must demonstrate a high return on investment considering that access to financing is always limited.

In examining the role of the Canadian government in supporting GSCM, government aid is targeted to specific investments promoting the use of new technologies having a positive environmental impact or allowing the country and a province to position itself through regional or global competition. The recent case of General Motors building a USD $500 million factory in Quebec, to make an integral component of electric-car batteries, with as co-investors, a South Korean company, the Government of Canada, and that of Quebec is a good example.[36]

Another example is Canada’s Innovation Superclusters Initiative launched in 2019. It pulls together technology clusters across the country into industry-led consortiums. Each supercluster focuses on supply chain technology innovation in ocean sciences, artificial intelligence, advanced manufacturing, the protein industry, and digital technology. The federal government has provided USD $30 million to date for five superclusters in the USD $950 million flagship innovation program with an ambitious goal of adding tens of thousands of new jobs and growing the economy by tens of billions of dollars by 2028.[37]

Another example is the Smart Cities Challenge funded by Infrastructure Canada, a pan-Canadian competition that is open to all municipalities, local or regional governments, and Indigenous communities. The Challenge empowers communities to adopt a smart cities approach to improve the lives of their residents through innovation, data, and connected technology.[38] The circular economy and related business models are at the core of this initiative.

Of course, we must mention the various GHG emission reduction and carbon neutrality targets that the Canadian government and the provincial governments are adopting. Canada’s Climate Plan announced at Cop26, includes a goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. The Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, proclaimed in 2021, enshrined this goal into law.

In March 2022, the Trudeau Government delivered its 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan. It is a roadmap that outlines a sector-by-sector path for Canada to reach its emissions reduction target of 40 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050. The Plan outlines current and new policies by the Government of Canada to meet its GHG reduction targets and in some cases, associated funding.

With such ambitious targets, the mechanisms of a carbon market alone will not be enough for Canadian companies to invest massively and quickly in the decarbonization of their operations and supply chains. This is a real revolution, nothing less!

It's a safe bet that all Canadian levels of government will have to play with the carrot and the stick to obtain buy-in from the private sector. The measures that will be put in place will certainly take the form of loans, fiscal and parafiscal incentives and perhaps even direct subsidies.

As for the status of the adoption of GSCM in Canada, in general, Industry Canada Ministry published in 2009, in collaboration with the Supply Chain & Logistics Association Canada, a global survey on the state of GSCM in Canada.[39] They issued three booklets giving a Canadian perspective on GSCM:

- Logistics & Transportation Services

- Retail Chain & Consumer Product Goods

- Manufacturing

Although this survey is over ten years old, it gives us a good idea of the Canadian industry's perception of GSCM and how they are integrating the concept into their operations.

For the companies that have adopted and implemented GSCM practices, the main findings are illuminating. To begin with, the high cost of energy and fuel is the main driver for implementing GSCM practices in manufacturing and distribution activities.

Additionally, a large portion of Best-in-Class (BiC) businesses increased their use of multi-modal transportation (e.g., decreasing air and truck transportation and increasing rail and marine transportation) to maximize environmental and business benefits.

The three groups of companies implementing GSCM practices see improvements in energy reduction, waste reduction, and reduced packaging in distribution activities. Furthermore, to be successful at GSCM, BiC logistics and transportation service providers are using highly advanced processes and technologies — both at the corporate level and within their distribution centers and transportation operations. Additionally, most BiC businesses can better differentiate their distribution services, improve risk management, increase sales, and increase access to foreign markets, all while reducing distribution costs.

Finally, since many GSCM practices require limited investment, are low-risk, and offer short-term return-on-investment periods, businesses of all sizes can engage in these activities.

Canadian companies that are currently engaged in GSM practices follow in the footsteps of those surveyed in the 2009 study.[40] These enterprises prioritize energy efficiency and reducing energy consumption and waste. This validates our hypothesis that most organizations go for the low-hanging fruit first and tackle operational issues to improve their environmental footprint.

Those that act upstream of their supply chains are mainly part of major brands with activities in Canada. They apply the strategies and programs adopted by their parent companies adapting them to the Canadian context.

Overall, what is the outlook for GSCM in Canada and North America?

Adoption and implementation of GSCM practices are no longer discussed and evaluated on an ad hoc basis, but are considered at a broader level and more from a disclosure perspective. This is the result of the high adoption rate of ESG scoring frameworks and systems.

There are now institutions and bodies developing ESG frameworks and guidelines; firms and organizations developing performance standards and appraisal systems; service providers evaluating company performance, and ESG investment funds and their asset managers. For most investors, private and institutional, ESG reports provide material information upon which investors can rely to make investment and voting decisions. Therefore, for a stock company, good ESG performance is now part of their strategy and action plan to acquire capital.

Many draw a parallel between a company's ESG performance, its exposure to risks and its ability to manage and adapt to them. The ESG score becomes an indicator of the company's resilience and its ability to create value. It is for this reason that the evaluation of ESG performance extends beyond the circle of listed companies and quickly spreads to their suppliers. Supplier prequalification and qualification processes and tools are adapting rapidly to ESG principles and terminology.

Companies must look beyond their operations and consider all impacts throughout their supply chains. Requirements for impact disclosure will only increase and put more and more pressure on organizations.

Conclusion

The governments and private sectors of the US, Canada, and Mexico—individually and collectively—are advancing policies and actions to support the greening of supply chains. Article 24.2 of the USMCA itself states: “The Parties recognize that a healthy environment is an integral element of sustainable development and recognize the contribution that trade makes to sustainable development.”[41]

Green supply chain practices incorporate sustainability concepts with a special emphasis on reducing carbon emissions and minimizing waste management while maximizing profits. Through both necessity (regulations) and choice (corporate credo) companies are rethinking their use of materials, reusing waste or by-products, cutting back on packaging and redesigning processes while optimizing transport.

For companies, it is not a case of pure altruism or cajoling (or requirements) from governmental authorities. Newer production technologies—products and processes—have “green” built in on the front end. Simply stated, these advancements achieve the dual purpose of avoiding negative environmental impacts while increasing firm-level efficiency and productivity.

The benefits resulting from the greening supply chains will produce dividends for current and future generations and further the goal of a healthier planet. In that regard, Canada, the US and Mexico—individually and collectively—are doing their utmost to contribute to that goal through improved greening of their supply chains.

**The authors extend their deep gratitude to Siddharth Upadhyay, doctoral student at FIU, and Pat Campbell of Supply Chain Canada for their invaluable assistance with this monograph.**

[1]This lifecycle includes product design, development, materials selection, manufacturing, transportation warehousing, distribution, consumption, return and disposal. www.sustainable-scf.org

[2] Samir K. Srivastava, “Green supply-chain management: A state-of-the-art literature review,” International Journal of Management Reviews 9, no. 1 (March 2007): 53-80 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00202.x

[3] Khan, Green Practices and Strategies in Supply Management.

[4] Martin Murray, “Introduction to the Green Supply Chain,” LiveAboutDotCom, January 21, 2019, https://www.thebalancesmb.com/introduction-to-the-green-supply-chain-2221084

[5] “Guide to sustainable and green supply chain practices,” Agility Group.

[6] Kristie Pladson, “Activist investors push firms to go green,” DW, January 27 2022, https://www.dw.com/en/activist-investors-pressure-firms-to-go-green/a-60570878

[7] Anmar Frangoul, “Activist investors and a ‘greenwashing’ backlash: Change is coming to the corporate world,” CNBC, January 25, 2022

https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/25/activist-investors-greenwashing-backlash-change-is-coming-to-business.html

[8]“Gartner Announces Rankings of the 2022 Global Supply Chain Top 25,” Gartner, May 26, 2022,

https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2022-05-26-gartner-announces-rankings-of-the-2022-global-supply-chain-top-25

[9] ”Supply Chain Sustainability,” Cisco, https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/about/supply-chain-sustainability.html

[10] ”Sustainable Sourcing,” PEPSICO, https://www.pepsico.com/our-impact/esg-topics-a-z/sustainable-sourcing#:~:text=Our%20approach%20to%20sustainable%20sourcing,corrective%20action%2C%20and%20capability%20building.

[11] Muhammad Amad Saeed and Wolfgang Kersten, "Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification, " Sustainability 11, no. 4: 1137 (2019), https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041137

[12] Ibid.

[13] Oracle, ”Retailers Support a More Sustainable Supply Chain with New Oracle Cloud Service,” Cision, June 22, 2022

https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/retailers-support-a-more-sustainable-supply-chain-with-new-oracle-cloud-service-301572641.html

[14] Saeed and Kersten, "Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification."

[15] Katie Jahns, ”The environment is Gen Z’s No. 1 concern – and some companies are taking advantage of that,“ CNBC, August 10, 2021

https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/10/the-environment-is-gen-zs-no-1-concern-but-beware-of-greenwashing.html

[16] R.M. Leffering, ”Enabler and barriers of sustainable supply chain management,“ 2020 https://edepot.wur.nl/521624

[17] ”Toyota Tsusho Group Supply Chain Sustainability Behavioral Guidelines,“ Toyota Tsusho Corporation,

https://www.toyota-tsusho.com/english/sustainability/social/supply-chain.html#:~:text=The%20Toyota%20Tsusho%20Group%20has,supply%20chain%20in%20each%20region.

[18] ”Toyota cuts global production again as semiconductor shortages, supply chain disruptions linger,“ Fox Business, June 22, 2022

https://www.foxbusiness.com/markets/toyota-cuts-global-production-semiconductor-shortages-supply-chain

[19] ”Sustainable Acquisition,” U.S. General Services Administration, https://www.gsa.gov/governmentwide-initiatives/federal-highperformance-green-buildings/resource-library/sustainable-acquisition

[20] ”The Biden-Harris Plan to Revitalize American Manufacturing and Secure Critical Supply Chains in 2022,“ The White House, February 24, 2022

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/02/24/the-biden-harris-plan-to-revitalize-american-manufacturing-and-secure-critical-supply-chains-in-2022/

[21] ” Benefits for the Environment in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement,“ Office of the United States Trade Representative,

https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/benefits-environment-united-states-mexico-canada-agreement

[22] USMCA, ”Chapter 31 Annex A; Facility-Specific Rapid-Response Labor Mechanism,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, 2019,

https://ustr.gov/issue-areas/enforcement/dispute-settlement-proceedings/fta-dispute-settlement/usmca/chapter-31-annex-facility-specific-rapid-response-labor-mechanism#:~:text=The%20USMCA%20includes%20an%20innovative,rights%20at%20the%20facility%20level.

[23] SEMARNAT, ”Se publica NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021, que establece límites de contaminantes en descargas de aguas residuales,“ Government of Mexico, March 11, 2022

https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/prensa/se-publica-nom-001-semarnat-2021-que-establece-limites-de-contaminantes-en-descargas-de-aguas-residuales

[24] Cynthia Aceves, ”Logística verde: 10 empresas que la realizan con éxito,” The Logistics World, November 9, 2020

https://thelogisticsworld.com/planeacion-estrategica/10-empresas-exitosas-que-realizan-logistica-verde/

[25] ”Leading hydrogen and fuel cell sector associations in Canada and Mexico announce MOU to promote collaboration,“ CHFCA, February 9, 2022

http://www.chfca.ca/2022/02/09/leading-hydrogen-and-fuel-cell-sector-associations-in-canada-and-mexico-announce-mou-to-promote-collaboration/

[26] Jum’a, Luay, Muhammad Ikram, Ziad Alkalha,and Maher Alaraj, ”Factors affecting managers’ intention to adopt green supply chain management practices: evidence from manufacturing firms in Jordan,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29, 5605–5621 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16022-7

[27] Procuraduria Federal de Proteccion al Ambiente, ”PROGRAMA NACIONAL DE AUDITORÍA AMBIENTAL A LAS EMPRESAS INTERESADAS EN PARTICIPAR, Y AQUELLAS QUE PARTICIPAN EN EL PROGRAMA NACIONAL DE AUDITORÍA AMBIENTAL,” Government of Mexico, September 26, 2022,

https://www.gob.mx/profepa/acciones-y-programas/programa-nacional-de-auditoria-ambiental-56432

[28] "Normas Mexicanas,” Government of Mexico, https://www.semarnat.gob.mx/gobmx/biblioteca/nmx.html

[29] María José Goytia, “Mexico, Canada Sign MOU to Collaborate in Green Hydrogen,“ Mexico Business News, February 21, 2022 https://mexicobusiness.news/energy/news/mexico-canada-sign-mou-collaborate-green-hydrogen: ”Leading hydrogen and fuel cell sector associations in Canada and Mexico announce MOU to promote collaboration,“ CHFCA.

[30] Raúl Camba, Pablo Ordorica Lenero, and Rafael Scott, ”How Mexico Can Harnass it’s Superior Energy Abundance,” McKinsey and Company, November 22, 2019, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/oil-and-gas/our-insights/how-mexico-can-harness-its-superior-energy-abundance

[31] “Catálogo Nacional de Indicadores,” SNIEG, 2020 https://www.snieg.mx/cni/escenario.aspx?idOrden=1.1&ind=6200105287&gen=2915&d=n

[32] Srivastava, “Green supply-chain management: A state-of-the-art literature review.“

[33] Arthur Nelson, “Agribusiness giants tried to thwart EU deforestation plan after Cop26 pledges,” The Guardian, March 4, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/mar/04/agribusiness-giants-tried-to-thwart-eu-deforestation-plan-after-cop26-pledge?CMP=Share_AndroidApp_Other

[34] Alexis Bateman and Leonardo Bonnani, “What Supply Chain Transparency Really Means,” Harvard Business Review, August 20, 2019, https://hbr.org/2019/08/what-supply-chain-transparency-really-means

[35] Ibid.

[36] Marisa Coulton, “General Motors returns to Quebec to build 'cathode active material,' not Camaros,” Financial Post, March 7, 2022, https://financialpost.com/commodities/energy/electric-vehicles/general-motors-returns-to-quebec-to-build-cathode-active-material-not-camaros

[37] “Innovation Superclusters Initiative,” Invest in Canada, https://www.investcanada.ca/programs-incentives/innovation-superclusters-initiative

[38] Government of Canada, ”Smart Cities Challenge,” Infrastructure Canada, https://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/cities-villes/index-eng.html

[39] Industry Canada Ministry is currently the Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada Ministry; Supply Chain and Logistics Association Canada is currently Supply Chain Canada; ”Logistics in Canada,” Government of Canada, www.ic.gc.ca/logistics

[40] Industry Canada, Green Supply Chain Management—Manufacturing, A Canadian Perspective, Ottawa, 2009. https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/365250/publication.html

[41] ”United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement,” Office of the United States Trade Representative, June 1, 2020 https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/agreement-between

Authors

Professor of International Business and Executive Director for the Americas, College of Business, Florida International University

Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition

The Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition works to shape conversations and inspire meaningful action to strengthen technology, trade, infrastructure, and energy as part of American economic and global leadership that benefits the nation and the world. Read more

Canada Institute

The mission of the Wilson Center's Canada Institute is to raise the level of knowledge of Canada in the United States, particularly within the Washington, DC policy community. Research projects, initiatives, podcasts, and publications cover contemporary Canada, US-Canadian relations, North American political economy, and Canada's global role as it intersects with US national interests. Read more

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more