A blog of the Latin America Program

Bienvenidos a Uruguay. ¿Adiós Argentina?

Uruguayan President Luis Lacalle Pou has made attracting migrants a major policy priority, with the hopes of turning Uruguay into “a destination, not only for our Mercosur neighbors, but for the world.” His optimism is buoyed by Uruguay’s political stability in a region beset by a whirlwind of crises, from Argentina’s economic troubles and Brazil’s polarized politics to Venezuela’s humanitarian disaster and Chile’s social unrest.

Mr. Lacalle Pou’s pitch to migrants reflects his recognition that Uruguay is a small and aging society with an increasingly stretched pension system. Inflows would also help compensate for the loss of hundreds of thousands of Uruguayans beginning in the 1950s, a period of economic and political decline that challenged the country’s image as a magnet for European immigrations. In all, 633,000 Uruguayans live outside the country, 18 percent of the country’s population of 3.4 million. By contrast, only 2 percent of Argentines live outside its borders.

A Long Decline

In the first half of the twentieth century, Uruguay was a major recipient of migrants. From 1900-1950, almost 520,000 moved to Uruguay, mainly from Southern Europe. In the prosperous period after World War Two, Uruguayans called their country the “Switzerland of South America,” and drew poor migrants to expanding urban industries. Yet Uruguay’s fortunes soon changed. Increased government expenditure and regulation stifled the economy, as the costs of a generous welfare state and patronage system overburdened Uruguay’s export sector. As lower commodity prices also stung Uruguay’s farmers, the country slid into a prolonged economic and social crisis in the 1960s and 1970s.

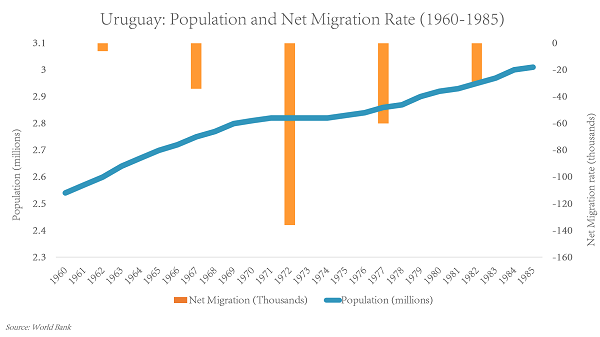

Between 1957-1962, only 6,000 Uruguayans left the country. But after 1963, as political violence increased, outward migration grew rapidly. By the end of the military dictatorship (1973-1985), 380,000 had left the country. (My own parents exited in 1969 for Canada – a more exotic location for an Uruguayan is hard to imagine.) The outflows were so severe during this period that Uruguay’s population barely grew.

Democratization, and moderate economic growth in the 1980s and 1990s, slowed emigration. However, the economic crisis between 1999-2002 reversed that trend, sending 104,000 Uruguayans abroad. As Uruguay’s economy recovered in the 2000s, emigration slowed once again. This year, the net migration rate is projected to be -0.9 emigrants per 1,000 residents, a post-1985 low.

Incentives

The large number of Uruguayans outside the country is an unappreciated asset. Expatriates sent home $104 million in 2018 in remittances. But Mr. Lacalle Pou sees greater value in luring them home, where they could be a valuable source of human, social and financial capital.

To incentivize the return of Uruguayan expats – as well as other high-income migrants – the new government plans to lower residency requirements. In all, Mr. Lacalle Pou hopes to increase the population by as many as 100,000.

A particular target for Mr. Lacalle Pou are well-off Argentines. Already, Argentina’s economic crisis appears to be sending a steady stream across the Río de la Plata, and there is reason to believe many more might soon make the trip. The most emblematic case is Marcos Galperin, the CEO of one of Argentina’s most important technology firms, MercadoLibre, who recently decamped for Uruguay. As Argentina’s recession enters its third year, news reports in Buenos Aires are detailing the advantages of life in Uruguay for Argentine businesses and high net worth individuals, and even highlighting investment opportunities.

Indeed, the pro-market policies of Uruguay’s center-right government present tax and regulatory competition with its far larger neighbor. Mr. Lacalle Pou’s recruitment drive was further helped by Argentine President Alberto Fernández’s steep tax increases and restrictive capital controls, which threaten to stifle investment and growth.

Como Uruguay no Hay

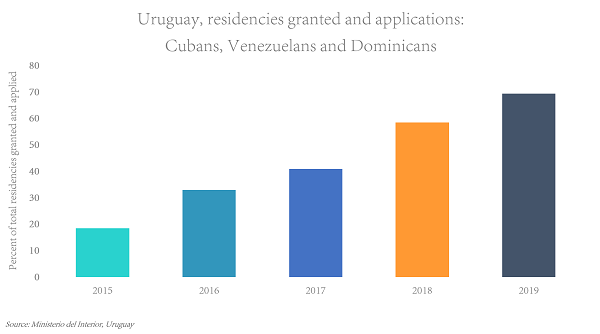

Uruguay, meanwhile, is not only a haven for the region’s elite. In recent years, it has also welcomed thousands of migrants from Venezuela, Cuba and the Dominican Republic. Between 2016-2019, those countries represented one-third of the 12,000 residency permits issued by Uruguay. In 2019, Cubans accounted for 63 percent of residency applications.

The influx of tens of thousands of migrants to Uruguay could reshape politics in the small country. Although Uruguayan expats are not allowed to vote, residents are permitted. If Uruguay manages to add tens of thousands of new residents, it will become a far more diverse and dynamic environment. But as in other countries that have experienced rapid migration, Uruguay’s newcomers could provoke a reaction. One red flag was the sudden rise of the nationalist, right-wing Open Forum party, a member of the governing coalition, whose leader has made xenophobic remarks about migrants. For now, however, most Uruguayans seem eager to accept migrants with open arms.

Author

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution