A blog of the Latin America Program

Chile should be a COVID-19 success story, riding its rocket-speed vaccination campaign to economic reopening and recovery. Unlike its neighbors, who have struggled to obtain vaccines and lean heavily on the World Health Organization (WHO), Chile had administered at least one dose to more than 70 percent of its population by July 18, ahead of all but four countries. After facing criticism in 2020 for his pandemic management, President Sebastián Piñera had become an immunization superstar for his ambitious vaccine purchases and rollout.

Instead, Chile faced a deadly spike in COVID-19 cases in April and again in late May. On June 12, the capital, Santiago, entered another lockdown, as daily cases exceeded 7,000. Under the new rules, only essential workers were permitted to leave home for work; outdoor recreation was limited to the morning, and only with members of the same household; and shopping was restricted to twice a week for two hours. Almost all hospital beds were full, and the healthcare system was pushed to its limits.

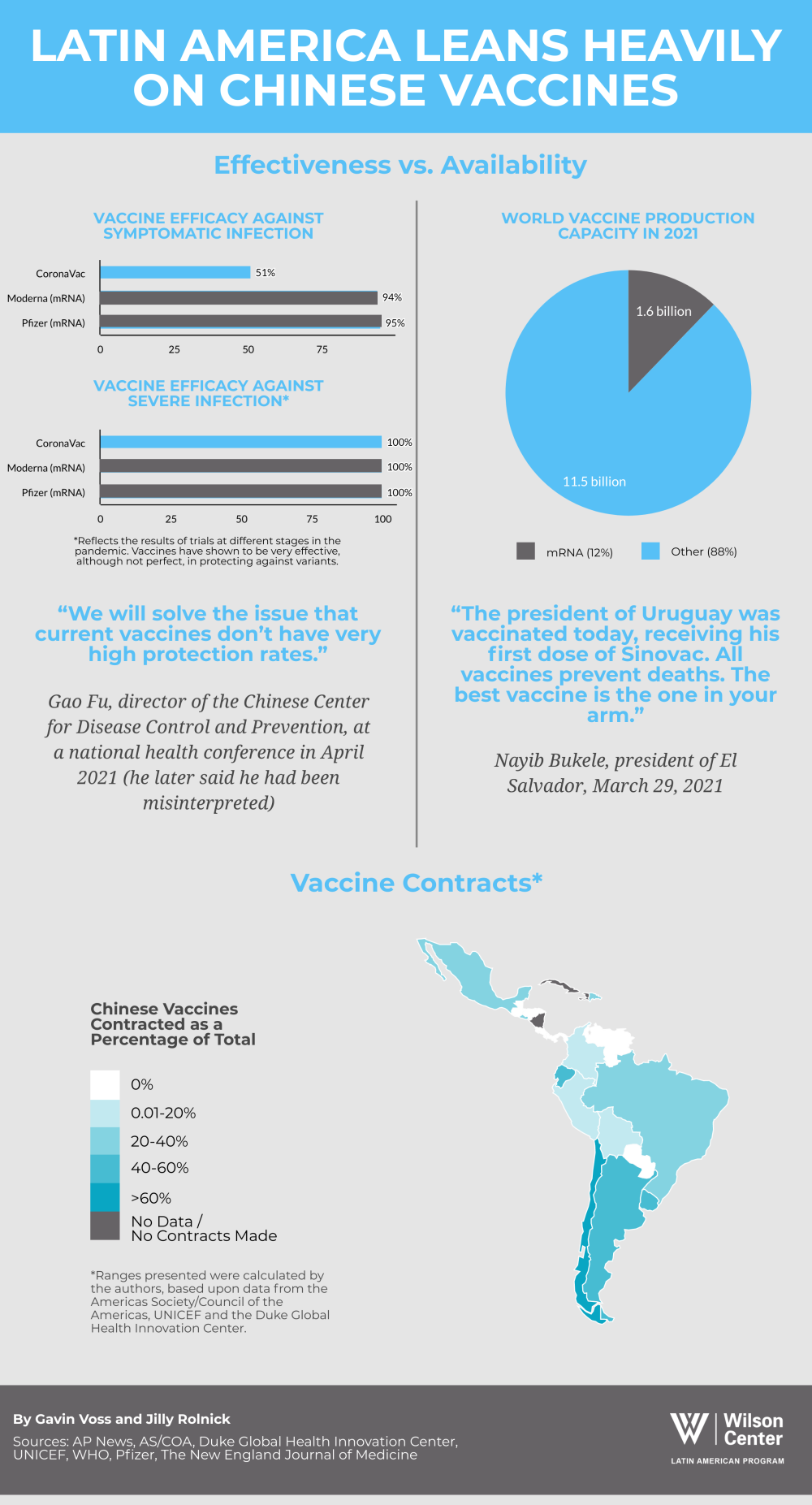

The reason for Chile’s unexpected struggles? Its reliance on the CoronaVac vaccine, produced by the Chinese company Sinovac, as well as a rushed reopening and a premature tapering of social distancing.

Chile purchased massive amounts of CoronaVac doses at a time when the U.S. government was not yet exporting U.S.-produced mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna, or the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. As it turned out, CoronaVac is effective; a study by the Universidad de Chile found that the vaccine prevents infection in 54 percent of vaccinated individuals two weeks after the second dose. Unfortunately, the same study found its effectiveness is only 3 percent after one shot. CoronaVac accounts for 75 percent of vaccine doses administered in Chile and for many Chileans, a false sense of security is a dangerous side effect of the Chinese vaccine.

CoronaVac trials in other countries have produced vastly different results. Studies in Turkey, Indonesia and Brazil calculated the vaccine’s effectiveness against symptomatic infection to be 84 percent, 65 percent and 50 percent, respectively. The WHO approved the vaccine for emergency use in May 2021, making it eligible for the organization’s COVAX vaccine distribution initiative.

But Chile is not the only country where widespread inoculation with Chinese vaccines failed to slow the coronavirus’s spread, at least initially. In Indonesia, for example, hundreds of health care workers tested positive for the coronavirus in June despite receiving the CoronaVac vaccine; some ended up hospitalized. That situation worsened in July, with 114 doctor deaths in the first half of the month. COVID-19 deaths in the Seychelles skyrocketed despite a successful campaign with China’s Sinopharm vaccine. Bahrain, Mongolia and the United Arab Emirates also bet big on Sinopharm and had similar outcomes.

In late June, Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi upset Chilean officials by dismissing the value of Chinese vaccine technology, which he said had “shown itself not to be adequate.” Countries with high rates of immunization that relied on non-Chinese vaccines, including the United States, Israel and the United Kingdom, have seen better results, though the highly infectious Delta variant is complicating their disease control.

For Chile, the choice of vaccine was not the only factor causing its latest wave of the pandemic. As its vaccination drive progressed, the government sent mixed messages about the country’s reopening and provided incomplete information about the Chinese vaccine’s effectiveness, particularly after only one shot. The trouble began in March, when Chile not only reopened schools, but also permitted the resumption of indoor sports and the operation of casinos. Health experts, including the Consejo Nacional del Colegio Médico, say the government failed to consult with scientists before easing social distancing measures. Public disregard for pandemic regulations also contributed to a rise in infections.

Today, Chile has greater control over the virus, with a rate of new infection not seen since last year. Still, As the Delta variant spreads in Latin America, Piñera has announced $2 billion in new pandemic spending, including for the purchase of five million additional vaccine doses. In recent weeks, Chile has purchased millions of Pfizer doses. Public health authorities are also considering administering a third shot to Chileans, potentially of an alternative vaccine.

If it decides to administer a third dose, Chile would be following in the footsteps of countries such as the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, which are offering booster shots of either Pfizer or Sinopharm to strengthen the protection of those who have already received two doses of the Sinopharm vaccine. Indonesia has also rolled out a Moderna booster shot for health care workers who received the CoronaVac vaccine.

Throughout Latin America, AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines purchased through the WHO have begun to arrive. Latin America is also receiving millions of vaccines donated by the United States; Bolivia, El Salvador, Honduras and Haiti have received U.S. doses donated through the WHO, while Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay have benefited from U.S. “vaccine diplomacy” through direct donations.

But Chile is not the only country in Latin America seeking pandemic salvation in Beijing. Brazil, Mexico and the Dominican Republic have purchased 100 million, 20 million and 10 million doses of the CoronaVac vaccine, respectively. Additionally, Mexico (12 million doses) and Argentina (10 million doses) both have large vaccine contracts with Sinopharm.

Like Chile, Uruguay is a case of high reliance on Chinese vaccines. It has vaccinated much faster than most of its South American neighbors, with 61 percent of its population fully inoculated against COVID-19 as of July 20. But to achieve that pace, 70 percent of the doses administered in Uruguay have been CoronaVac vaccines. As a result, like Chile, Uruguay saw accelerated COVID-19 spread despite rapid inoculation, with new cases and deaths reaching record highsin April and May after it lifted most pandemic restrictions.

Authors

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution