"Da, da" or "nyet, nyet"? Brezhnev, Tanaka, and the Unresolved Russo-Japanese Territorial Dispute

Russian archives provide new insights into Japanese and Soviet/Russian efforts to resolve the dispute over the "northern territories."

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Russian archives provide new insights into Japanese and Soviet/Russian efforts to resolve the dispute over the "northern territories."

Judging by the frequency of meetings between Prime Minister Abe Shinzo of Japan and the Russian President Vladimir Putin, Russo-Japanese relations are as friendly and robust as they had ever been.

True, the economic indicators continue to disappoint. Bilateral trade has only just begun to recover from the steep post-2013 plunge but remains a very long way off the historic highs of 33 billion USD. Japanese foreign direct investment – about 2 billion dollars – is miserly even by Russia’s investor-unfriendly standards.

But the economic realities notwithstanding, Abe and Putin have managed to develop a constructive, positive relationship, one that is closer, in any case, than that of any previous Japanese leader with a Russian counterpart.

Abe, like his many predecessors, has long hoped to conclude a peace treaty with Russia. The sticking point here is Japan’s insistence on the return of the “northern territories” (the four islands of the Kurile chain: Etorofu/Iturup, Kunashiri/Kunashir, Shikotan, and the Habomai islets). This the Russians – and before them, the Soviets – had resolutely refused to do, although in 1956 then-Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev promised to return two of the four, Shikotan and Habomai, when the peace treaty was concluded (the offer was subsequently withdrawn but in recent years re-advertised).

To encourage Putin, Abe has controversially dangled the promise of Japanese investment on the disputed islands, something that Tokyo had long been reluctant to do.

After meeting Putin again on September 10, 2018, Abe highlighted his resolve in finding the solution to the territorial problem “within the lifetime of our generation.” But the prospects for the peace treaty are as dim as ever. The Russians – already enjoying a reasonably close, dynamic relationship with Japan – see no reason to give in. The fact that Abe is even trying as hard as he is speaks either to his self-delusion, or his self-confidence, or just plain stubbornness.

These qualities are nothing in new in a Japanese Prime Minister. One man who possessed all three in equal measure was Tanaka Kakuei (Prime Minister in 1972-74), nicknamed “the Bulldozer” for his less-than-refined political tactics. Tanaka’s singular contribution to Japan’s foreign relations was the 1972 Sino-Japanese normalization. He is not as well known for his overtures to the Soviet Union.

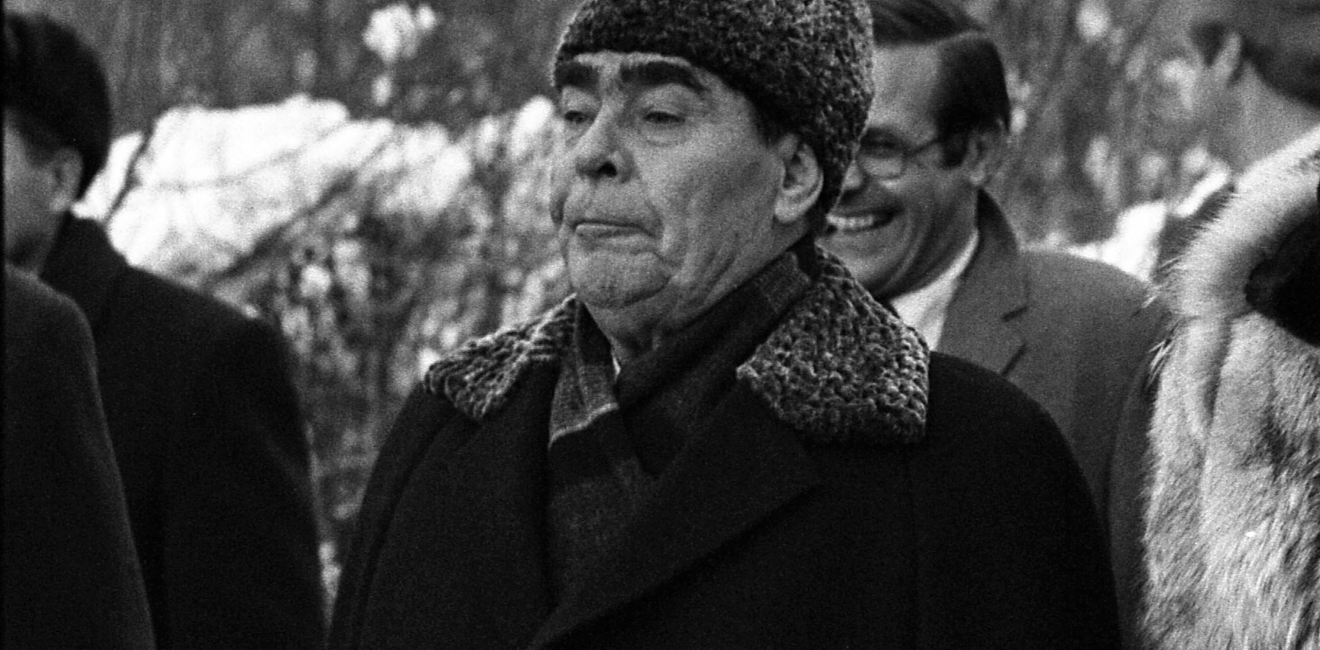

It was Tanaka, however, who became the first Japanese Prime Minister in 17 years to set foot in the USSR when, in October 1973, he travelled there for talks with the General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party Leonid Brezhnev.

The records of these meetings have now been declassified in Russia. Today, the Cold War International History Project is posting the translated memoranda of conversations of the two days—October 8 and October 9—of discussions between the Soviet and the Japanese leaders.

To understand the context: both the Soviets and the Japanese thought they held the best cards. Leonid Brezhnev basked in the glory of détente. Nixon’s visit to Moscow in May 1972, followed by Brezhnev’s tour of the United States in June 1973, set the stage for a closer Soviet-American relationship, and bolstered the Soviet standing as a superpower equal of the United States. With better relations came the prospects of increased trade and American investment in oil and gas projects in Siberia.

The Japanese, with their technologies and their energy appetites, were welcomed, but there was a sense in Moscow that theirs was a seller’s market and that they could pick and choose between the insatiable capitalist investors.

Tanaka also spoke from strength. Japan emerged from the 1960s as an industrial powerhouse. Its share of the Soviet trade was already higher than that of any other capitalist country. There was an expectation in Tokyo that Japan’s economic leverage would help in extracting political concessions from the USSR.

Moreover, the Soviets needed Japan’s friendship in Asia at a time of deep hostility in Sino-Soviet relations. China and the USSR narrowly managed to avoid an all-out war after the 1969 border clashes but the Soviet leaders were deeply suspicious of China’s intentions. These suspicions were only deepened by the dual shock of the Sino-American rapprochement and the Sino-Japanese normalization. Mindful of a potential quasi-alliance between China, Japan, and the United States, Soviet policy makers had every reason to seek a political breakthrough with Tokyo, and this objectively strengthened Tanaka’s hand.

In short, Tanaka and Brezhnev came to the talks thinking that ‘they need us more than we need them.’ They also came with diametrically-opposing agendas. Brezhnev wanted economic cooperation; Tanaka, the return of the “northern territories.”

The Japanese Prime Minister broached the subject right away, telling Brezhnev, poetically: “Although a man is not eternal, the human kind will exist always. We must think about our relations. We must solve questions if they exist. There are such questions.” Calling the four islands a “drop in the sea,” compared to the vast territory of the Soviet Union, Tanaka asked to settle the peace treaty there and then.

Brezhnev dodged the bullet, leading the discussion towards developmental projects in Siberia. Later that evening Tanaka again brought up the peace treaty, only to meet with Brezhnev’s rebuff. The General Secretary promised to continue the negotiations but – in what later became Moscow’s basic position – proposed that the two sides do more to develop bilateral relations, while putting the territorial question on the backburner.

Tanaka had hoped to use the economic lever to extract Soviet concessions on the islands but Brezhnev seemed to think that Japan would be – or at least should be – interested in developing economic relations for their own sake.

Tanaka persisted, directly linking the two issues: “The main aim of my visit to the Soviet Union is the settlement of the question of the peace treaty and the four islands of the Kurile chain. If these questions, which are the most important ones, are settled, then the prospects for solving other questions will open up.” In response, Brezhnev merely called for mutual understanding.

During the final day of talks, on October 9, Brezhnev and the Soviet Prime Minister Aleksei Kosygin made a renewed effort to win Tanaka’s commitment to economic projects in the Soviet Union. To this end, they needlessly and awkwardly dangled the threat of American competition. Tanaka rightly cut them short: “it is your business which country to prefer.” He then returned to the territorial issue, asking that it be included in the final communique. Without this, he added, the communique would be “meaningless.”

The “Bulldozer” thus proved himself worthy of the nickname, but Brezhnev did not take such pressure lightly. The conversation suddenly turned very ugly. “Yesterday we already expressed our considerations on this question,” Brezhnev said. “Perhaps you did not pay sufficient attention to them, so I will repeat them.” He went on to explain that although the Soviets would not refuse to conduct negotiations on the peace treaty, “one could not determine all the conditions of the treaty in one sitting.” Foreign Ministers could continue their meetings, while for the time being the two countries could conclude a treaty on peaceful cooperation and good neighbourly relations.

The back-and-forth continued for some time, with Kosygin even pressing Tanaka to take his words (about the “meaningless” communique back). The Russian record of the meeting ends with a rather abrupt exchange:

“L.I. BREZHNEV. […] I would like to note that for two days our negotiations were characterized by the spirit of good neighbourliness and good will. If you want to cross this out, say so directly.

K. TANAKA. No, I don’t want that.

L.I. BREZHNEV. We approach the fact that you raised this question with understanding but this does not mean that we can agree with your position.”

Japanese historians have argued that one important result of the Brezhnev-Tanaka summit was that the Soviet leaders finally agreed that the conclusion of a peace treaty would entail the resolution of the territorial dispute. This interpretation comes from a particular reading of the joint communique, which stated that the two sides would negotiate a peace treaty by resolving the “unresolved questions since WWII.”

According to Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, “Tanaka later explained that he had asked Brezhnev to make doubly sure that ‘unresolved questions’ included the territorial issue and that Brezhnev affirmed this twice by answering, ‘Da, da’.”[1]

The documentary record does not support this interpretation, instead giving credence to the Russian claim that Brezhnev never made such promise. Tanaka first pushed to specifically mention the “northern territories” in the communique. Brezhnev refused. Then the Prime Minister proposed to refer to the two sides agreeing to “continue the negotiations on the peace treaty, including the territorial question.” “This is impossible,” Brezhnev replied bluntly. “This is an even broader formulation. At one time, as a result of a war, Japan took possession of half [the island of] Sakhalin. This is also a territorial question, although at the time we did not raise it.” There was no “da, da.” Not even a maybe.

For all his bulldozer tactics, Tanaka got very little – almost nothing – to suggest that the Soviets were prepared to unfreeze their long-held position. Brezhnev’s flexibility, such as there was, was simply a ploy to attract Japanese investment.

Hasegawa is correct in one important observation. The summit was a “clash of two nouveaux riches who wanted to do everything to remind the other that the two were not in the same league.”[2]

This was too bad, for in retrospect 1973 was the best opportunity to resolve the territorial problem that Tokyo and Moscow had before or since. Brezhnev was at the height of his power and influence, and also still in relatively good health. Before long he succumbed to sclerosis; by the late 1970s he was no longer capable of making daring, independent decisions.

The next opportunity to tackle the territorial problem did not arise until the late 1980s. But Mikhail Gorbachev was more interested in European matters than he was in the fate of Soviet-Japanese relations. When he finally came around to tackling the problem – in 1990-1991 – he was already too weak politically to make the required concessions, even though he needed, desperately needed, Japanese investments. The same constraints plagued Yeltsin’s efforts to tackle the problem, and, voila, forty-five years later, the territorial issue is in a deadlock that Brezhnev and Tanaka would immediately relate to.

Will it be resolved “within the lifetime of this generation,” as Abe hopes? This seems unlikely. The two sides’ strategies are broadly the same as those of their Soviet predecessors. Abe is willing to separate politics and economics, promising Japan’s participation in economic development projects.

Putin is willing to let the Japanese government deliver on these promises, while postponing the resolution of the territorial question to the uncertain future. Unlike Brezhnev, he does not even need Japan on board. Moscow’s relations with China are politically close and economically profitable.

And so, we are back to Tanaka’s poetry: “Although a man is not eternal, the human kind will exist always.” Perhaps one day, more sensible representatives of the human kind will look back on the Russo-Japanese territorial dispute, and wonder: what, exactly, was that all about? Only, it may take longer than Tanaka or, indeed, Abe ever thought possible.

[1] Hasegawa Tsuyoshi, The Northern Territories Dispute and Russo-Japanese Relations, Vol. 1, p. 156.

[2] Ibid., p. 157.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more