Documenting the Soviet ICBM Program

Asif Siddiqi introduces seven Russian documents on the development of the Soviet ballistic missile program and the creation of the R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile in 1957.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

Asif Siddiqi introduces seven Russian documents on the development of the Soviet ballistic missile program and the creation of the R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile in 1957.

Seven documents from Russian archives provide a brief and skeletal look into the development of the Soviet post-World War II ballistic missile program that culminated in the creation of the R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile in 1957.

Document No. 1 is the first major Soviet government resolution that committed resources to the development of long-range ballistic and cruise missiles. Issued on May 13, 1946, it is now considered the foundational document of the Soviet space program for it created the seed managerial and R&D institutions of the space program. This resolution created a “Special Committee for Reactive Technology” to oversee the missile program at the highest level, headed by Politburo member Georgii Malenkov (who was replaced as chairman by Nikolai Bulganin in 1947). As attested in the document, at the time, the entirety of Soviet research on long-range missiles was based on creating copies and derivatives of captured German missiles such as the V-2 (called the “FAU-2” here) and the Wasserfall. It assigned several R&D organizations to focus on replicating the German missiles, most importantly, the Scientific-Research Institute No. 88 (NII-88), the antecedent of the Energia Rocket-Space Corporation, the leading Russian space organization of the 21st century.[1]

Document No. 2 was a short report prepared by the Minister of the Defense Industry Dmitrii Ustinov on October 15, 1951, on the sum contributions of the German scientists, designers, engineers, and technicians forcibly relocated to the Soviet Union in October 1946. The document, addressed to Lavrentii Beria, the manager of Soviet strategic weapons programs (including the atomic bomb, long-range missile, and air defense projects) gives a technical but succinct account of German contributions to the Soviet effort. All the Germans were repatriated back to the German Democratic Republic by 1953.[2]

Document No. 3 was signed by Stalin on February 13, 1953, formally initiating the development of an intercontinental missile. As the document attests, both ballistic and cruise missile options were pursued. Once again, the lead organization is identified as NII-88 with Sergei Korolev in charge.

Document No. 4, dated November 25, 1953, specifies, for the first time, putting a nuclear bomb on a rocket, a “strategic” rocket known as the R-5.[3] This letter from Viacheslav Malyshev, the new manager of Soviet strategic weapons development (his formal title was the Minister of Medium Machine Building) to Georgii Malenkov and Nikita Khrushchev specifically calls for a missile carrying a nuclear warhead that could hit Europe, the Near and Middle East, and Japan.

Document No. 5 is a government decree from February 12, 1955, that approved the formation of a new launch range to test intercontinental missiles, both of the ballistic kind (the R-7) and cruise missiles (Burya and Buran). This range, which was located in Kazakhstan near the town of Tiura-Tam was henceforth called the Scientific-Research and Test Range No. 5 (NIIP-5) and later, the Baikonur Cosmodrome. It eventually became the birthplace of the Soviet space program as both Sputnik and Iurii Gagarin took off from this range.

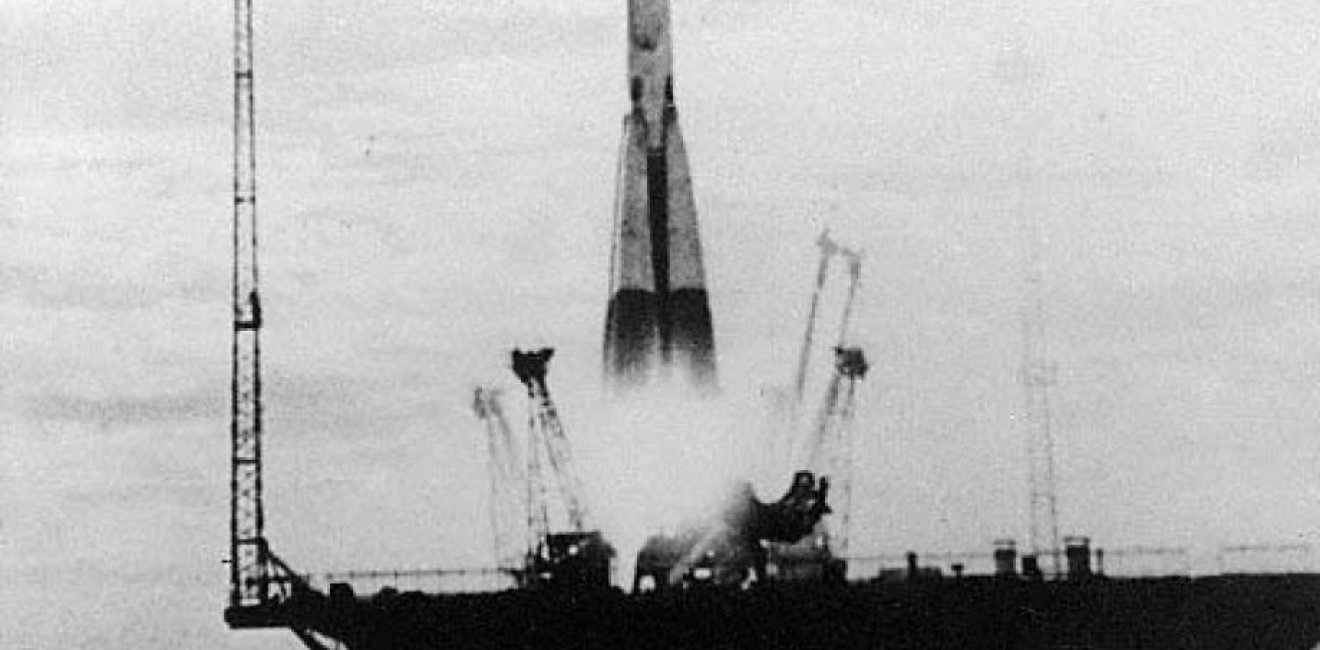

Document No. 6 is a letter addressed to Nikita Khrushchev from Vasilii Riabikov (the industrial manager of the long-range ballistic missile program) and Chief Designer Sergei Korolev, reporting on the status of the development of the R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). The letter, dated April 10, 1957, states that the first launch, from Tiura-Tam, is imminent.

Document No. 7 is an official report from several industrial managers, military officers, and Chief Designer Sergei Korolev to Nikita Khrushchev reporting on the results of the first launch of the R-7 ICBM carried out on May 15, 1957. The report, issued a day later, notes that the rocket flew perfectly for 70 seconds before deviating from the planned trajectory.

[1] For more on this stage of Soviet missile development, see Asif A. Siddiqi, The Rockets’ Red Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

[2] For an in-depth look at the fate of German rocket designers in the Soviet Union, see Asif A. Siddiqi, “Germans in Russia: Cold War, Technology Transfer, and National Identity,” Osiris, 2nd Series, Vol. 24 (Science and National Identity), eds. Carol E. Harrison and Ann Johnson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 120-143.

[3] For more on the Soviet bomb project, see David Holloway, Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy, 1939-1956 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more