A blog of the Latin America Program

Downtrodden in a Shut Down

The quickly spreading COVID-19 pandemic is testing countries’ healthcare capacities globally, as exponential growth in cases, and the severity of the disease, push some of the world’s best healthcare systems to the brink.

These challenges are acute in Latin America, where healthcare systems rank well below those in North America and Europe, raising concerns about the region’s ability to handle adequately a surge in patients. For now, the absolute number of confirmed infections in the region remains low, though that is likely the result of inadequate testing. Even so, the growth rate is high.

Governments in the region recognize the peril. With a few notable exceptions – namely Brazil, Mexico and Nicaragua – most Latin American countries have imposed strict social distancing measures, including mandatory quarantines.

On March 20, for example, Argentine President Alberto Fernández followed Panama and Peru in imposing a national lockdown to slow the virus’s spread, despite severe economic consequences for a country already teetering on default. Unlike Panama and Peru, which had healthy economies and access to credit prior to the outbreak, Argentina was entering its third year of recession. “If the dilemma is the economy or life, I choose life,” he explained. But now, Mr. Fernández must show that the economic sacrifices were worth it, flattening the curve rapidly so he can prevent a collapse of the country’s already spotty healthcare system, avoid overtaxing its already strained social services and budget, and safely phase out the isolation measures.

So far, the public is on his side. Mr. Fernández, elected with 48 percent of the vote in October, has seen his approval rating jump to 69 percent. But Argentina’s coronavirus caseload keeps growing, now at 1,628, according to the World Health Organization. And the challenge of virus control is daunting.

What is particularly concerning to Argentine authorities is the well-being of the country’s 10 million poor, many of whom lack access to sanitation and healthcare. Nearly 1 million Argentine households live in one of the country’s 4,416 informal settlements, known as villas, sometimes without potable water. Many of them work in Argentina’s large informal sector, depriving them of important government services, benefits and labor protections.

Unprepared for the Fight

The COVID-19 crisis will produce the worst year for the world economy since the 2008 global financial crisis, and “the worst growth year in Latin America in the last 50 years,” according to the International Monetary Fund. Argentina is particularly ill-prepared to address this economic fallout, even as it potentially faces disproportionately severe public health impacts.

Even before the outbreak, Argentina’s economic prospects were dim. A likely default, anti-competitive economic policies, sagging tax collection, spiking unemployment and flagging exports had analysts projecting a 1.2 percent contraction for this year. Now, the Economist Intelligence Unit forecasts a 6.7 percent contraction.

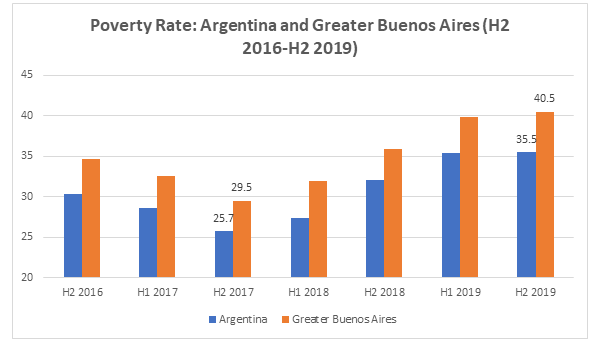

Before the pandemic, the poverty rate had reached 36 percent, an increase of almost ten percentage points from two years earlier. Extreme poverty was 8 percent, almost double the rate from two years earlier – a result of a weak labor market, and high inflation bludgeoning real wages for those still employed. Real salaries declined by 16 percent between 2015 and 2019. Last year, Argentina lost 167,000 private sector jobs, as the unemployment rate hit 9 percent.

Today, economic conditions are far worse. Given languid activity, the government’s strategy of raising taxes has predictably failed to stem falling revenue, and additional taxation during a deep recession would be injurious. As long as the country delays its debt restructuring, meanwhile, it will remain shut out of credit markets. That has left one option to pay for stimulus measures: printing pesos. For Argentina, a country with a notoriously poor track record of controlling inflation, that approach is raising alarms.

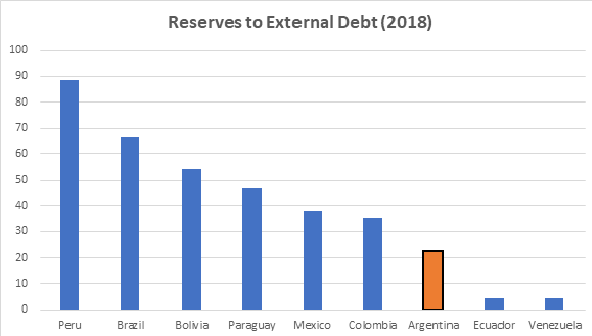

Another disadvantage for Argentina is its failure to save during boom times. Unlike Chile, Argentina did not set aside a portion of its extraordinary revenues during the commodity super cycle of the 2000s. As a result, it finds itself in the same condition as other vulnerable emerging markets, such as Zambia, Turkey and South Africa, with no meaningful rainy day fund to tap.

First, Fighting the Disease

From an epidemiological perspective, Mr. Fernández’s decision to shut down the economy was the right one. Indeed, despite hyper-polarization, a large majority of Argentines support the quarantine, and Mr. Fernández, like other world leaders who have adopted dramatic public health measures, has seen his approval rating shoot up.

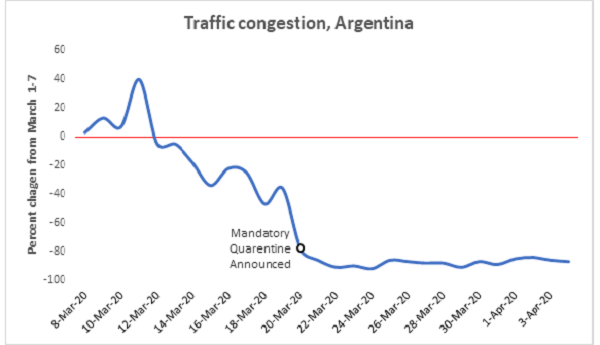

That public support is not only politically advantageous; it has also translated into a high degree of compliance with the lockdown. Google’s geolocation data shows the quarantine is being rigorously observed, with a near total drop-off in transit and visits to retail and recreational establishments.

But it is not clear how long Argentina can sustain the quarantine’s economic and social costs.

The lockdown is particularly painful for laborers in Argentina’s large informal economy, which accounts for 36 percent of the workforce. From day laborers to street vendors, millions of poor and working-class Argentines have seen their incomes evaporate overnight thanks to the quarantine. Going forward, their continued adherence might depend on whether the government meets their basic needs, including food for their families. As one informal worker put it, “the truth is that I am not concerned about the coronavirus, I just don’t want this to stop us from eating.”

Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?

The social situation in Greater Buenos Aires is of particular concern, as it is home to a third of the country’s population, including many vulnerable Argentines.

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, unemployment in Greater Buenos Aires stood at 10 percent. Poverty had increased rapidly since 2017, reaching 41 percent last year.

It is too soon to obtain data on the employment effects of the crisis, or its impact on poverty. But early indications are worrisome. Since the start of the quarantine, the region has seen a 40 percent increase in the use of communal kitchens. Countrywide, those relying upon food support has reached 11 million, an increase of 3 million people. Since communal kitchens complicate social distancing, the Argentine military has begun delivering food handouts.

Nowhere Else to Turn

These increasing social needs – arising from the coronavirus’s health and economic impacts, and the consequences of the nationwide quarantine – are imposing huge burdens on Argentina’s national and provincial authorities at a time of exceedingly scarce resources. Unlike a typical economic crisis, social distancing rules inhibit charities and political parties that might otherwise help distribute goods to those in need.

This problem is not unique to Argentina. Brazil faces similar challenges in its favelas, for example. In Guayaquil, Ecuador, the pandemic has produced a humanitarian catastrophe for the city’s poor. But the concern is particularly elevated in Argentina, which lacks the resources or borrowing capabilities of other countries in the region that it needs to strengthen its health sector and shelter its most vulnerable populations from the economic collateral damage of virus control measures.

Author

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution