A blog of the Africa Program

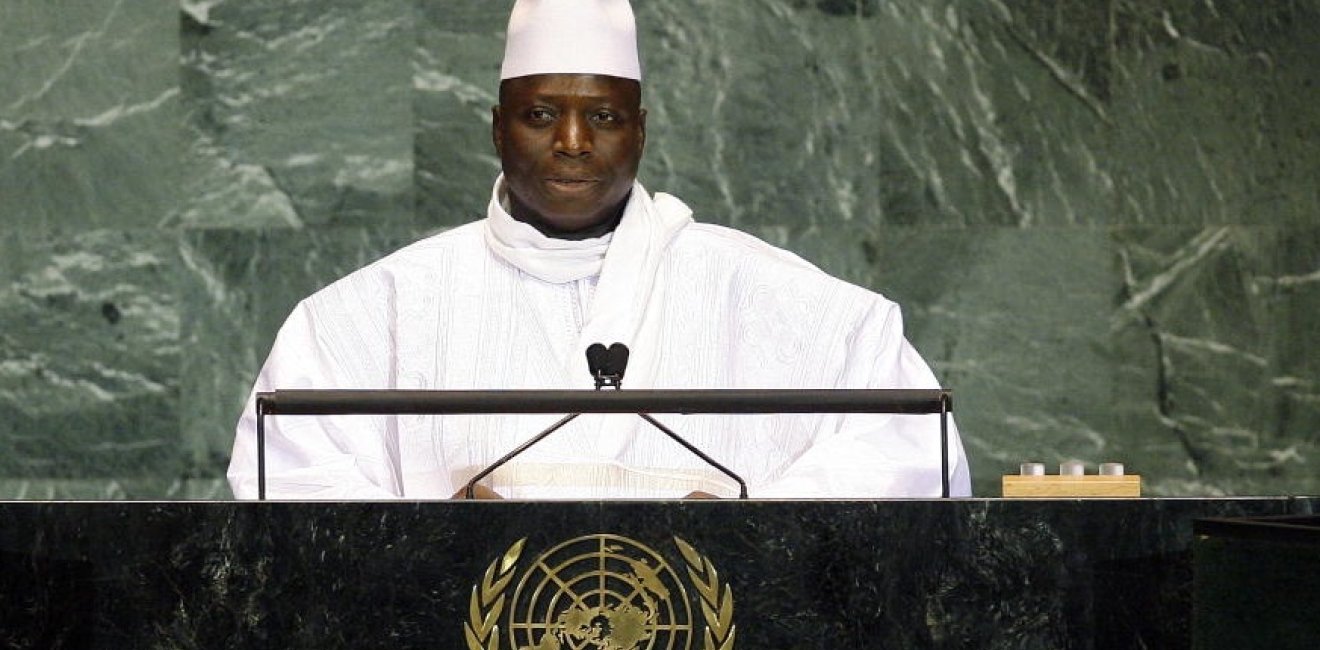

[caption id="attachment_12026" align="aligncenter" width="600"] President Yahya Jammeh addresses the United Nations. UN Photo/Erin Siegal, via Flickr. Creative Commons.[/caption]

Once again the sudden and forceful stream of anti-incumbent fervor has resulted in the unexpected defeat of an African leader, this time an authoritarian one who held power for 22 years. The defeat of Gambia's President Yahya Jammeh follows the electoral wins of Muhammadu Buhari in Nigeria, and Patrice Talon in Benin. More recently, Ghana's President Mahama, an incumbent seeking a second term suffered a humiliating defeat to the main opposition leader Nana Akufo Addo. A familiar current which runs through these electoral victories was the resounding vote against incumbent regimes.1

That President Jammeh was so confident of victory, and did not effectively rig the elections was quite unusual, and perhaps uncharacteristic of a leader who proclaimed he would hold power for one billion years, "if God wills it." For someone who has been accused of rigging elections in the past, that this election was conducted without subverting the will of the people is intriguing. Of course, the deployment of anti-democratic tactics was not in short supply. Indeed, it was the result of the massive crackdown of prominent opposition elements such as Ousainou Dabo, the founder and presidential candidate of the United Democratic Party (UDP) in previous elections which paved the way for the then treasurer and now President-elect Adama Barrow to become the leader of the UDP and ultimately leader of the coalition which eventually won the 2016 elections. Coupled with this was the banning of international observers, a social media blackout on election day, the blocking of local and international phone calls, the repression of the media, and more. Despite these, many were impressed with the swiftness with which President Jammeh accepted the verdict of the Gambian people. It was a harbinger of a new democratic future for the tiny West African nation. However, the sudden reversal is deeply troubling and could lead to instability.

The conventional wisdom of most political observers of West Africa is that President Jammeh may have lost the election because of his authoritarian leadership style. It is true he ruled with an iron fist, hounding opposition forces and suppressing perceived dissent, to the extent of even shutting down any contact with the outside world on election day by blocking social media and international phone calls. However, this is only part of the story. What has festered for several years but may have escaped pundits is the poor economic record resulting in massive unemployment. Like most incumbents in Africa, Jammeh failed to tackle the fundamental human need for employment, which requires strategic policies and a long-term vision. His government's inability to provide jobs for the teeming masses has resulted in scores of unemployed Gambians annually embarking on the perilous journey to Europe via the Mediterranean in search of a better life. The UNDP 2014 National Human Development Report for the Gambia estimated that the youth are the cohort with the highest unemployment rate at 38 percent. Approximately 37 percent of the Gambian population is aged between 13-30 years. It is also the case that between 2013 and 2016, real per capita GDP is estimated to have fallen by 20 percent, suggesting increasing levels of poverty.

Similarly, it seems likely that Jammeh overestimated his own popularity and thought he had done enough to provide infrastructure (roads, schools, hospitals, etc.). Given the infrastructure deficit in the Gambia, like many other African countries, these projects seem to have had something of an impact. For instance, construction of schools increased gross enrollment ratio from 63 percent in 1994 to 94 percent in 2014. Incumbent governments often calculate that touting and displaying such visible projects could lead citizens into retaining them. However, these projects shroud the symptoms of a much deeper economic malaise. In most cases, hospitals and schools were built without corresponding equipment for effective delivery of services. Voters are becoming aware that infrastructure provision is not enough without corresponding improvement in economic conditions. By World Bank figures, the Gambia's economy grew by just 0.9 percent in 2014. The country has seen uneven economic performance with a negative growth rate of -4.3 percent in 2011. Worse, by the end of 2015 the stock of public debt had sharply increased to 108 percent of GDP, from about 84 percent at the end of 2013. Thus, 40 percent of government revenue was used to pay interest on public debt. This figure was estimated to increase to 50 percent in 2016.

These economic conditions meant that the circumstances for an anti-incumbent vote were in place. Opposition forces presented a united front, unlike in many elections across the continent where opposition parties fail to compromise on a single candidate. Presenting Adama Barrow as the candidate of a coalition of seven political parties was a masterstroke. The combined votes for the President-elect (45.5 percent), and the third-party candidate Mama Kandeh (17.8 percent) totaled 63.3 percent, an indication of a resounding vote against Jammeh (36.7 percent).

Lessons

President Jammah's electoral defeat is a salutary reminder of the need for African governments to focus on the difficult task of improving economic conditions — particularly creating jobs — rather than entirely focusing on infrastructure projects, which in most cases are paid with borrowed loans rather than any carefully calibrated and internally generated funds. The likelihood is rising that incumbents who are not able to satisfy demands for job creation will be voted out. This job-motivated anti-incumbent backlash has caused the electoral defeats of Goodluck Jonathan in Nigeria, John Mahama in Ghana and now Jammeh — which was largely unexpected. Opposition parties are riding on the poor economic performance and job creation records of incumbents to create anti-incumbent fervor. This trend is likely to continue if the factors driving it remain undiminished.

Isaac Ofosu Debrah is an Independent Development Consultant and keen observer of West African politics. He is also a former Southern Voices Network Scholar at the Wilson Center.

1: In Nigeria, Muhammadu Buhari defeated the incumbent president, Goodluck Jonathan, in his bid for a second term in 2015. In Benin, President Yayi Boni was constitutionally barred from a third term. Patrice Talon defeated the candidate of Boni's party, Prime Minister Lionel Zinsou.

Author

Africa Program

The Africa Program works to address the most critical issues facing Africa and US-Africa relations, build mutually beneficial US-Africa relations, and enhance knowledge and understanding about Africa in the United States. The Program achieves its mission through in-depth research and analyses, public discussion, working groups, and briefings that bring together policymakers, practitioners, and subject matter experts to analyze and offer practical options for tackling key challenges in Africa and in US-Africa relations. Read more

Explore More in Africa Up Close

Browse Africa Up Close

The Innovative Landscape of African Sovereign Wealth Funds